At the beginning of the 1900s, Chelsea, Massachusetts, was slowly transforming from an agricultural society to an urban and industrialized one. Industrialists needed people to work in their factories and that meant work for new immigrants like Samuel Gass. Rural Americans had left their farms to meet the demand but more labor was still needed. Immigrants, first from the British Isles, and then from southern and eastern Europe flooded Boston and other cities. Chelsea eventually became the haven for thousands of Jewish immigrants, who, like Samuel Gass, came to America to seek a new life.

In 1830, Chelsea was a mere 1.5 square mile peninsula housing four farms and thirty people. The tidal channels of the harbor, Chicken Creek and Mystic River, isolated Chelsea from Charlestown and East Boston. A creek and marshland separated it from Revere. Only with Everett did Chelsea share a dry land border. Though it was located only a mile across the harbor from Boston, Chelsea was hardly influenced by the changes that affected that metropolis because at that time no bridge connected the two locales and ferry service was nonexistent.

Then in 1831, ferry service was instituted. Boston’s burgeoning, land-hungry population spilled across the harbor. By 1860, 12,000 people lived in Chelsea. The first new settlers were well-off Bostonians who built sizable homes. In 1910, almost 42% of Chelsea’s residents were foreign born, however, and intense development created a plethora of small homes on tiny lots and tenements. By 1930, once tiny, rural Chelsea was home to 45,000 people.[1] It had become one of the most densely populated, industrialized cities in the United States.

The Chelsea Street Bridge, a drawbridge constructed between 1936 and 1937, is one of three bridges that now connect Chelsea with Boston. Credit: Historic American Engineering Record, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-HAER, MASS, 13-BOST,136-28]

The city was divided into districts, segregated by class. Broadway ran the full length of Chelsea from the harbor to its border with Everett, cutting the city in half. The waterfront area housed the industrial and commercial core of Chelsea. Near the waterfront, tenements and a mixture of industrial and institutional buildings bounded Broadway. In the midtown area, shops prevailed. Here and northeast of the industrialized area were the modest residences of many workers; beyond these were the houses of the more affluent. The most prestigious homes were located in Horn Hill, Mount Washington, and Mount Bellingham. Near Mill Creek and the Everett boundary, stately homes lined the street.

![Captains’ Row on Marginal Street in Chelsea Credit: Haskell, Arthur C., Historic American Buildings Survey, 1934. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction HABS, MASS, 13-CHEL,1-]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/chelseahouse076744puw.jpg)

Captains’ Row on Marginal Street in Chelsea

Credit: Haskell, Arthur C., Historic American Buildings Survey, 1934. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction HABS, MASS, 13-CHEL,1-]

![Cary-Bellingham Mansion, 34 Parker Street, Chelsea Credit: Branzetti, Frank O., Historic American Buildings Survey, 1941. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction HABS, MASS, 13-CHEL,4]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/mansion076748puw.jpg)

Cary-Bellingham Mansion, 34 Parker Street, Chelsea

Credit: Branzetti, Frank O., Historic American Buildings Survey, 1941. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction HABS, MASS, 13-CHEL,4]

Even the shopping districts were distinct. Along Broadway there were fourteen butcher shops belonging to Gentiles, and no Jewish butchers. On Arlington Street, there were twelve Jewish butcher shops and no Gentile butchers. The Mill Hill section and Polish section of town were very anti-Semitic. Jews felt they were locked out of certain places and certain vocations because of this prejudice.

In 1905, the Jewish population of Chelsea was 4,500. Ten years later in 1915, the population had more than doubled with 11,000 Jews in the city. Most Jews worked in relatively high status occupations. They were carpenters, tailors, clerks, bookkeepers, coal dealer, lawyers, physicians, and journalists. Many of the Jews moved in from Boston during the building boom that followed a terrible Chelsea fire on Palm Sunday in 1908. The conflagration had swept through Chelsea and destroyed almost the entire business section and many houses.

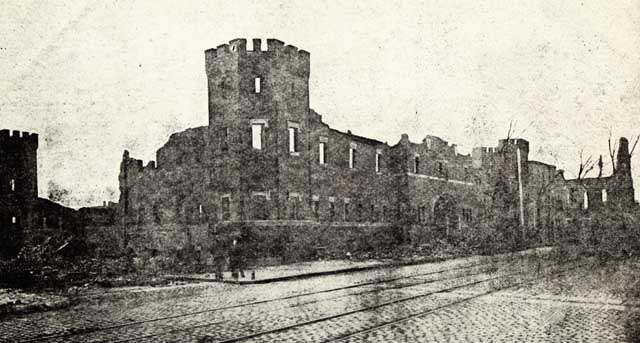

Ruins of the residential section on Chester Avenue after the big fire of April 12, 1908

Credit: Postcard published by N.E. Paper & Stationery Co., Ayer, Mass., 1908

Looking up Broadway from Third Street

Credit: Postcard published by N.E. Paper & Stationery Co., Ayer, Mass., 1908

All that remained of the Chelsea Armory, 1908

Credit: Postcard published by The Metropolitan News Company, Boston.

In 1915, Chelsea’s Jew population supported three synagogues and many Jewish political organizations such as the Chelsea Zionist Girls, Chelsea Young Zionists, Judean Juniors; two athletic associations—the Y.M.H.A. (Young Men’s Hebrew Association) and Y.W.H.A. (Young Women’s Hebrew Association); three lodges of the Independent Order of B’rith Abraham; as well as other Jewish organizations.

The Sunday School Class of 1934, Chelsea YM-YWHA. Back row, 2nd from left: Anna Gass; 2nd row from back, 2nd from left: Patty Gass

We do not know how much of Boston and the surrounding area that Sam Gass and other Kessel and Gass family members explored when they first came to Massachusetts. If they had ventured out of Chelsea, these are some sites that they could have seen:

![Boston Common, circa 1910 Credit: ©1910, Haines Photo Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: PAN US GEOG-Massachusetts no, 71]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Boston-commonw.jpg)

Boston Common, circa 1910

Credit: ©1910, Haines Photo Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: PAN US GEOG-Massachusetts no, 71]

![Boston Garden, 1904 Credit: ©1904, Haines Photo Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: PAN US GEOG-Massachusetts no, 77]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/bostongarden6a06389uw.jpg)

Boston Garden, 1904

Credit: ©1904, Haines Photo Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: PAN US GEOG-Massachusetts no, 77]

Commonwealth Avenue, Boston 1903

![Copley Square, Boston, 1903 Credit: ©1903, Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-D4-10736 R]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/copleysquare4a06563uw.jpg)

Copley Square, Boston, 1903

Credit: ©1903, Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-D4-10736 R]

![Marblehead’s harbor, 1906 Credit: ©1906, Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-D4-10946 R]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/marblehead4a06966rw.jpg)

Marblehead’s harbor, 1906

Credit: ©1906, Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-D4-10946 R]

Lars Garden

![Two views of the Massachusetts State House from 1903 and 1914 Credit: ©1903, E. Chickering & Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: PAN US GEOG-Massachusetts no, 83]. No credit information was given on the colorized postcard image, postmarked 1914.](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/pg4028w.jpg)

Two views of the Massachusetts State House from 1903 and 1914

Credit: ©1903, E. Chickering & Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: PAN US GEOG-Massachusetts no, 83]. No credit information was given on the colorized postcard image, postmarked 1914.

![Two views of Tremont Street, alongside the Boston Common in 1903. Both look northeast and on the left are entrances to the Park Street subway station and the Park Street Church. Credit: ©1903 E. Chickering & Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-USZ62-124335] and Credit: ©1904, Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-D4-17025]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/threeboston4a11337uw.jpg)

Two views of Tremont Street, alongside the Boston Common in 1903. Both look northeast and on the left are entrances to the Park Street subway station and the Park Street Church.

Credit: ©1903 E. Chickering & Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-USZ62-124335] and Credit: ©1904, Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-D4-17025]

![In 1903, the Boston Red Sox, then known as the Boston Pilgrims, played against the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. This photo was taken during one of the games in Boston. Credit: © September 26 1903 1903 E. Chickering & Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-USZ62-124335]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/baseball6a28813uw.jpg)

In 1903, the Boston Red Sox, then known as the Boston Pilgrims, played against the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. This photo was taken during one of the games in Boston.

Credit: © September 26 1903 1903 E. Chickering & Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-USZ62-124335]

![In 1914, the Boston Braves played the Philadelphia Athletics in the Worlds Series. This was photo was taken in Fenway Park. Credit: © October 112, 1914 John F. Riley. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-USZ62-122692]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/worldseries6a29764uw.jpg)

In 1914, the Boston Braves played the Philadelphia Athletics in the Worlds Series. This was photo was taken in Fenway Park.

Credit: © October 112, 1914 John F. Riley. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number:LC-USZ62-122692]

![These photographs of Boston was taken from across the Charles River in Charlestown, circa 1905. Credit: © between 1900 and 1910, Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: LC-D4-37111 L and 11R and LC-D4-37115]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/twoBoston4a19112uw.jpg)

These photographs of Boston were taken from across the Charles River in Charlestown, circa 1905.

Credit: © between 1900 and 1910, Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: LC-D4-37111 L and R and LC-D4-37115]