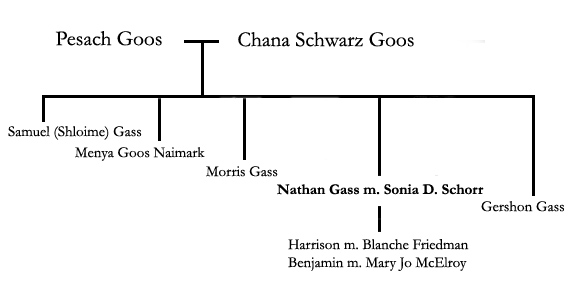

an Unconventional Pair

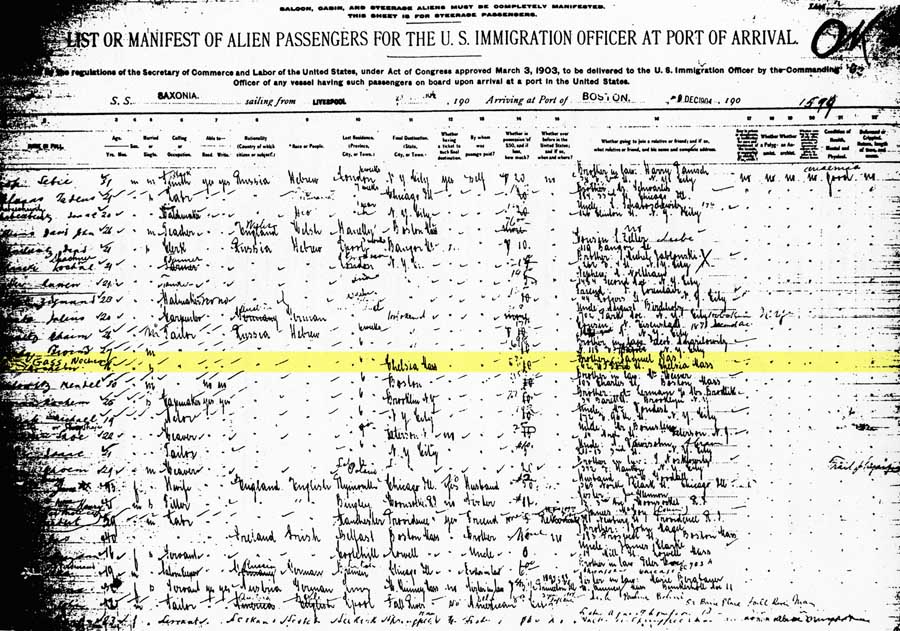

NATHAN PAUL (NOCHEM) GASS WAS BORN IN TURIYSK on October 28, 1888. At age 16, he followed his older brother Samuel to the United States, sailing on the S.S. Saxonia from Liverpool, England, on November 29, 1904, and arriving at the Port of Boston ten days later. [1]

Nathan Gass

In Russia, Nathan’s surname was “Goos,” but as happened to many immigrant families, the name was changed by American officials when he entered this country. As Harrison Gass, Nathan’s son, explained:

“Our last name was changed several times. When my father came over, an immigration official said, What’s your name?

My father answered, Nathan Goos.

So the official said, That’s not a good name for an American.

What’s a good name? asked my father.

Stone, came the answer. So my father became Nathan Stone.

“After a few years Nathan went to night school to learn English. After he learned some English he applied for naturalization papers. The immigration official asked him his name.

Well, he says, It’s Goos, but they changed it to Stone on me in Ellis Island.

The official said, That’s not legal, it’s too different. You can’t jump from Goos to Stone.

What’s legal American? asked my father.

Gass, replied the official. So then my father became Nathan Gass.”

According to the manifest: Nathan sailed in steerage, he had resided in England for six weeks before departing for America, and he was planning to join his brother Samuel Gas [sic] at 42 W. Third Street in Chelsea, Massachusetts. Nathan was age 16 years, single, and worked as a tailor. He had about $5.75 in his possession when he arrived in Boston and he had never been in the United States before.

Nathan Gass sailed to the United States on the Cunard Line’s SS Saxonia, which embarked from Liverpool, England on 29 November 1904 and arrived at the port of Boston on 10 December 1904. The manifest listed him under the name “Nochem Gus.”

When Nathan Gass immigrated to the United States, he spent six weeks in England. Did he see the White Cliffs of Dover as his ship approached Great Britain?

The Cliffs of Dover

Credit: ©between ca. 1890 and ca. 1900 Detroit Publishing Company. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsc-08355]

Nathan left England through the Port of Liverpool. These are some places he may have visited in Liverpool:

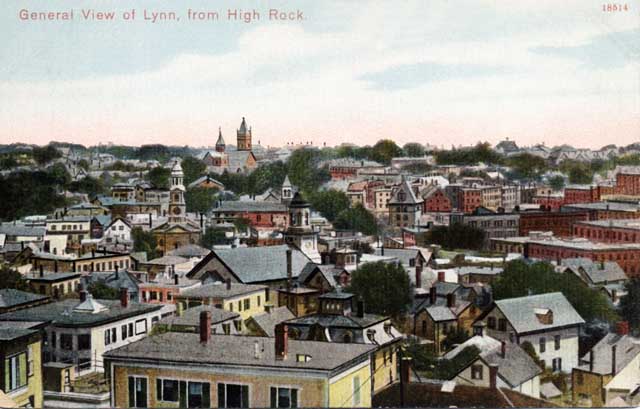

Nathan initially settled in Lynn, Massachusetts. As Harrison described it:

“When poor Ruskies came over here with no money—and my father didn’t have any money—it was customary for them to find somebody who had a couple of rooms to rent. My father rented a room from my mother, Sonia (Sophie) Dorson Shorr, who was married to a man called Phillip Schorr, and had two children, Albert and Dora. After about a year and a half my father ran off with Sophie to San Antonio, Texas. Maybe they had to run that far to rid themselves of scandal. Running off with a married woman was unheard of in those days. My mother divorced Schorr, married my father in 1912, and I was born in San Antonio, Texas, in 1913.

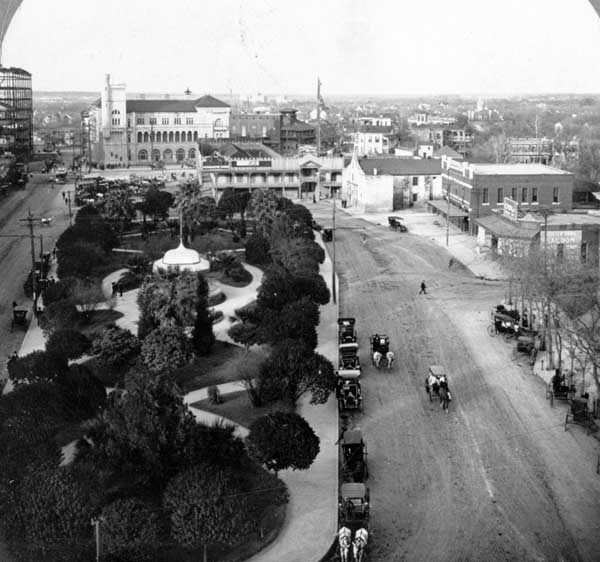

Panoramic view of San Antonio, Texas, 1910

Credit: © 1910 Haines Photo Co.. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-87798]The front of the Alamo, 1922

Alamo Square, 1909

Credit: ©1909 Keystone View Company, Meadville Pa. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ6-1920] and © 1922 Underwood & Underwood. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-87798]

San Antonio had a large military presence at the time Nathan and Sonya Gass lived there.

Credit: © 1911 George Grantham Bain. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction numbers LC-USZ61-1796, LC-USZ61-1795, LC-USZ61-1798, LC-USZ61-1797]Panoramic aerial view of Camp Wilson in San Antonio, Texas, 1917

Credit: © 1917 Charles W. Archer and Frank W. Hines. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [call number PAN US MILITARY – Camps no. 39 (F size) [P&P]“Nathan was in the fruit business in San Antonio, which meant he had a fruit stand, or he had a horse and buggy and went around selling fruit. He came back to Lynn [Massachusetts] to start Lion Shoe Company with his brothers. I don’t remember San Antonio at all so we must have left when I was very young. My brother Benjamin was born in Lynn in 1919.” [2]Nathan missed being in San Antonio for this 1905 reunion of President Teddy Roosevelt with the “Rough Riders”, the soldiers who had fought with him in Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

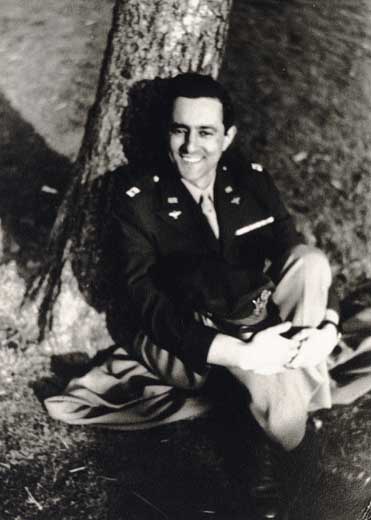

Credit: © 1905 Underwood & Underwood. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-97687]Harrison Gass

Bernard (Benny) Gass

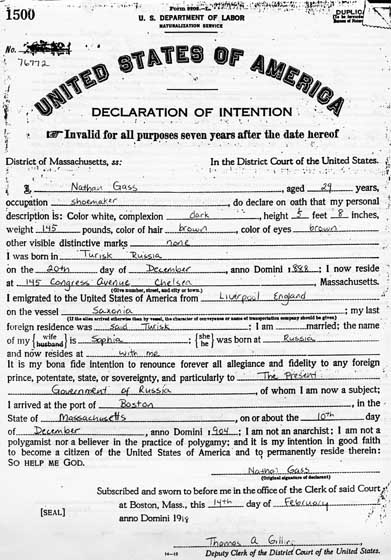

It appears from various documents that Nathan returned to Massachusetts by 1916, and that he moved back and forth between Chelsea and Lynn. Nathan’s petition papers (petitioning to become a citizen), filed in August 1916, listed the family address as 21 Brimblecom Street in Lynn.[3] His 1917 draft registration form shows that he was a self-employed shoe worker with a wife and two children living at 145 Congress Avenue in Chelsea. [4] The Lynn City Directory published in January 1918 shows a Nathan Gass, whose occupation was leather remnants, working at 49 Harbor and rooming at 22 Crosby,[5] and papers filed in 1918 declaring Nathan’s intention to become a U.S. citizen state that Nathan was a 29-year-old shoemaker living at 145 Congress Avenue in Chelsea.[6]

Nathan Gass’s Declaration of Intention

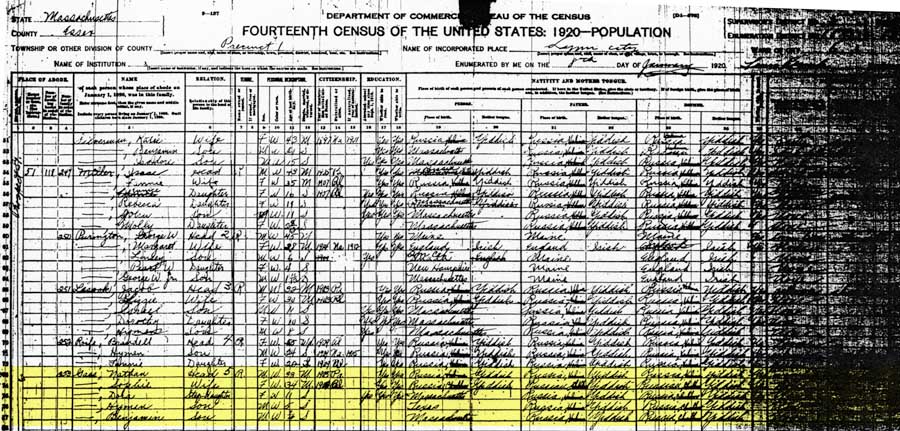

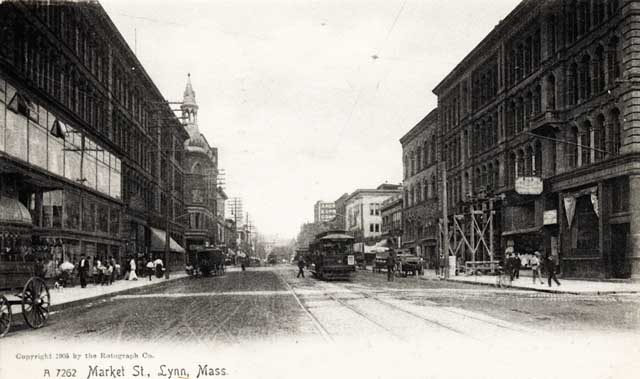

By 1920 the family had moved to 51 Prospect Street in Lynn and Nathan’s occupation was listed as “shoe shop.” [7] Perhaps this shoe shop was a precursor to Lion Shoe, which appears to have been established some time between January 1920 and the end of 1922, as the 1923 Lynn City Direction lists Nathan as the president of “Lyon” Shoe Company located at 195 Boston in Lynn.[8] The 1924 City Directory shows that Nathan had moved to 60 Franklin.[9] The 1925 Directory indicates that Lion Shoe moved to a new location, 61 Allerton.[10]

1920 census

View of Lynn from High Rock

Credit: T.W. Rogers Co., Publishers, Lynn, Mass. Made in Germany.

Lynn’s city hall

Credit: Souvenir Post Card Co., New York.

Market Street, 1905

Credit: The Rotograph Company, New York City, printed in Germany.

Lynn Shore Drive in moonlight

Credit: Tichnor Quality Views by Tichnor Bros., Inc., Boston, Mass.

Lafayette Park, Lynn

Credit: published by Mason Bros. & Co., Boston, Mass., 1913.

Bird’s-eye view of Lynn and Nahant from High Rock Tower

Credit: published by Mason Bros. & Co., Boston, Mass., 1911

Lynn High School, 1906

Credit: Souvenir Post Card Co., New York and Berlin

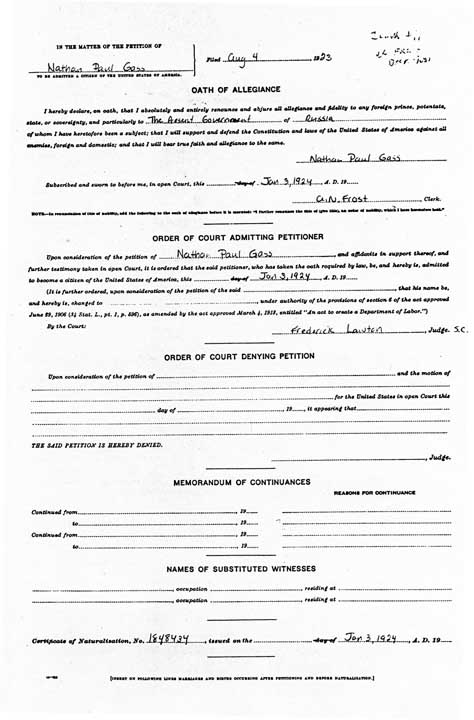

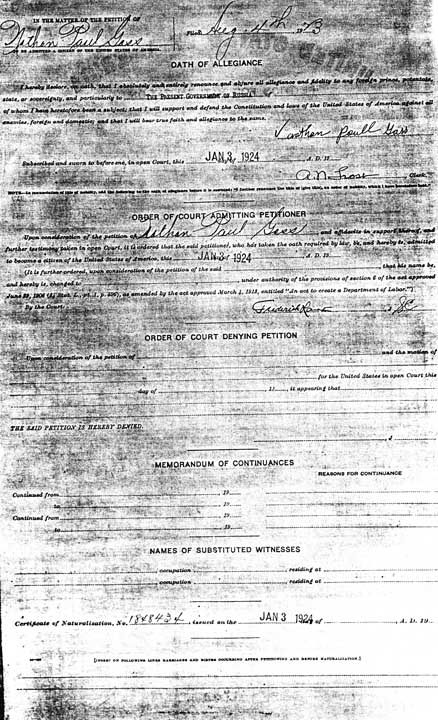

Nathan’s petition papers

Nathan was granted citizenship on January 3, 1924 and Sophie was naturalized on June 30, 1925.[11] Nathan’s son Harrison provided more details about his parents’ life.

“My mother was a lively and colorful woman, interested in music and poetry, and full of life. [Nathan] was not a very gregarious fellow, he was reserved and shy. But after Lion Shoe was established he used to travel around the country selling shoes.”

Sonya Gass, 1937

Harrison also explained a possible origin of the Lion Shoe Company:

“During Nathan’s first year as an immigrant in Lynn, he had worked at a shoe factory, and he was familiar with the manufacturing and merchandising of shoes. He had learned that he could go into business for himself–someone else would cut the shoes, he would stitch them together, and a third party would sell them.”

Harrison told how he joined his father and uncles at Lion Shoe:

“When I got out of college—Harvard—I was nineteen years old and didn’t exactly know what to do. I was offered two jobs as a part-time instructor while I studied for a Ph.D. One job was in economics and one was in music appreciation. And that sounded pretty good to me, to be a professor at Harvard. But I found out it only paid fifty dollars a week and that didn’t sound so good to me. Money is good to have. My father used to say, Rich or poor, it’s good to have a few dollars. So I decided I’d go into my father’s factory and learn how to make money. At that time my cousin Max Gass, Samuel’s son, was working for Lion Shoe and had been there a few years. Sam Gass, Morris’s son had been there for a year. And there was another partner’s son, Abraham Gootman’s son Georgie.

“I’d been there about six or seven months when finally the partners decided they were going to close the business. Not that they were broke. It was still profitable but it was getting more difficult. The way of making shoes had changed. Instead of stitching the bottoms on, everybody was cementing the soles on. The partners needed to change some equipment and they weren’t really up to it. They decided they’d better close the place.

“They weren’t ready to turn the business over to the younger people. They had an agreement that if they ever split up, none of their progeny would ever take over the factory because the others wouldn’t like it. I didn’t understand. Not that I knew much about it, but I knew I could run the business. I knew something, I could have paid them out in time, but they felt they’d all do it together or none of them, so they closed the factory.”

“They made money up until the day they closed and they split the assets equally among themselves.” [The space and machines had been rented].

Nathan retired in 1940 when Lion Shoe closed.

Harrison’s quotes were edited by Eleanor O’Bryon, the first editor of this family tree project.

Read Harrison’s original interview.

AFTER THE FACTORY CLOSED Harrison became an outside salesman and then he started a factory of his own—Shelburn Shoes—a year after Lion Shoe closed. About eight months later America entered World War II and Harrison sold the factory so he could enlist. He had a gentleman’s agreement with the new owner that when the war was over he could buy back half of the business, but the new owner had “forgotten” his promise by the time Harrison returned.

Blanche Friedman Gass

Harrison and Blanche Gass

Harrison served as an intelligence officer in World War II. After the war he married Blanche Freedman, an actress he had met during his tour of duty in Greenland. They settled in Newton, Massachusetts. Blanche performed in plays at the Brattle Theater in Cambridge, got a Masters Degree in Theater Education, and became a part-time professor of English and Drama at Tufts. Harrison and Blanche Gass had three children: Robert, Laurie, and Diane.

Harrison sold shoes for a Lynn/Swampscott man for several years. Then he opened his own business in Lawrence, Massachusetts. He eventually sold this factory to a chain, Morse Shoes, a big outfit with over 100 stores, and he was asked to stay on for five years to run the manufacturing end for the new owners. After the second or third year, he was asked to manage a group of eight shoe factories, which he did until he retired. Blanche died in 1963.

Harrison

Read about Harrison Gass’s experiences during World War II.

Harrison’s younger brother, Bernard (Benny) Gass became a pilot. He joined the Air Transport Command during World War II, flying transports, mainly in “the hump” from southern China into Northern India. After the war Benny married Mary Jo McElroy.

According to Harrison:

“The family promptly went into a catatonic fit. Mary Jo wasn’t Jewish. She was Scottish. Nice girl. She was a photographer from Des Moines, Iowa. They had a son, David.

“Benny flew for Northeast Airlines and took up with another girl. He and Mary Jo were on the verge of divorcing but he made an irretrievable error. He got killed.

“When the Korean War started Ben and I were both in the reserves. We were both called in and we went together to volunteer. He was accepted and I was temporarily turned down. I had bursitis and they gave me 90 days for a minor operation. Benny was sent to Boeing field, Virginia (outside of Washington, D.C.), where they put him to work training young pilots. He was to go on to Korea, but within two months there was a terrible accident, his plane crashed in and Benny died. As a sole surviving son under the Sullivan Law, I was no longer eligible to go to war.”

Both Nathan and Sophie outlived Benny. Nathan died in 1967; Sophie in 1969.