- Paul Gass, 1997

- Gittel Goldman

IN 1919, MY GRANDMOTHER Gittel Goldman Korff was killed during a pogrom—an anti-Jewish riot—in the Ukrainian town of Novograd Volynsk. She was only 29 years old and her four young children were by her side. Nearly 80 years later, I felt compelled to walk in the footsteps of my ancestors and I had an encounter with the same mindless prejudice that had led to Gittel’s murder. But I was oblivious to what was happening until after the danger had passed.

On a trip to explore the Ukrainian shtetls (villages) where my family once lived, I was passing through a town in the vicinity of Novograd Volynsk. My guide, Vitaly, pointed out a dilapidated area, which had once been the Jewish section.

I wanted to stop and have my photo taken next to a particularly picturesque ramshackle building. Vitaly argued against stopping, saying we had long distance to drive, but I insisted.

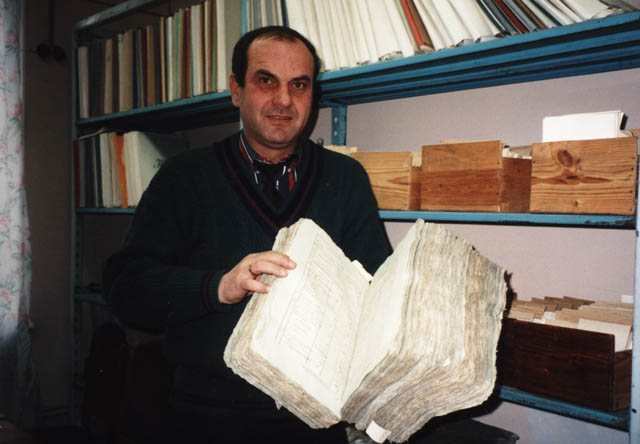

Vitaly Chumak not only served as my translator and guide, but he was thoroughly familiar with the holdings of the government archives in the region. Here he is in the State Archive of Zhitomir Oblast with the 1850 list of inhabitants who lived in Novograd Volynsk. Vitaly is a colleague of Miriam Weiner, who planned out my trip. Photo credit: Miriam Weiner of Routes to Root

I also wanted a photo of residents pumping water from a public well, their only source for household water. As I lingered, a few of the townspeople at the pump people began to talk to Vitaly, and he kept telling me to hurry. I had my back to Vitaly and couldn’t see that the crowd was not particularly friendly, and that even more people were walking quickly to join them. They were yelling at him to get the Jews away from their town, which of course I couldn’t understand because I didn’t speak the language. Vitaly finally got my attention and urged me to hurry into the car. He burnt rubber as we sped away.

When I asked what that was all about, Vitaly downplayed the threat and said something about the people in this town did not encourage visitors. However, my traveling companion, my 80-year-old uncle, Rabbi Baruch Korff, understood the language. He told Vitaly to tell me the complete story.

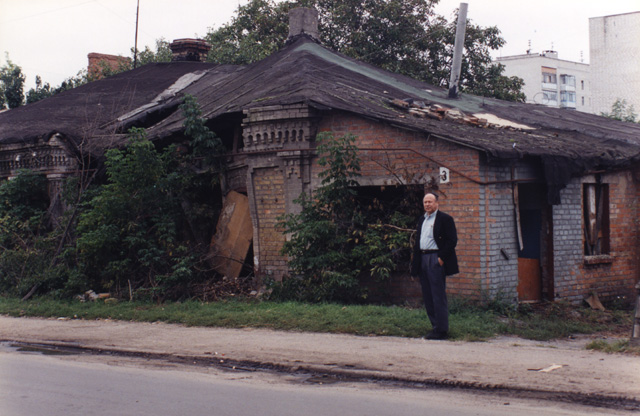

Paul standing in front of the ruins of a building in a Ukrainian town where

a few years prior to his visit a man was killed solely because he was a Jew

Vitaly then explained that the townspeople here were extremely antisemitic and Jewish visitors were not welcome. In recent years the local citizens had acted on theirprejudice and killed a Jew. Although I had been clueless, it was apparent from the tone of Vitaly’s voice and the look on Baruch’s face that we had been in a dangerous situation. This was the first time in my life that I had experienced a physical threat from anti-Semites and I had been too naïve to recognize it.

The menacing nature of the people on the street did not surprise Baruch. At age five, Baruch had witnessed the murder of his mother, Gittel, in Novograd Volynsk. Seven years after his mother’s death, Baruch immigrated to America, and as a young man he trained to be a rabbi. But Baruch was drawn to politics not the pulpit. Over the next 50 years he had an amazing career as a speechwriter for Congressmen, a diplomat, and an advisor to presidents. He never forgot his roots and was always a staunch advocate for the Jewish people. Baruch, however, is best known for his role as President Richard Nixon’s “rabbi” during the Watergate era.

- Baruch Korff in the White House with President and Mrs. Nixon

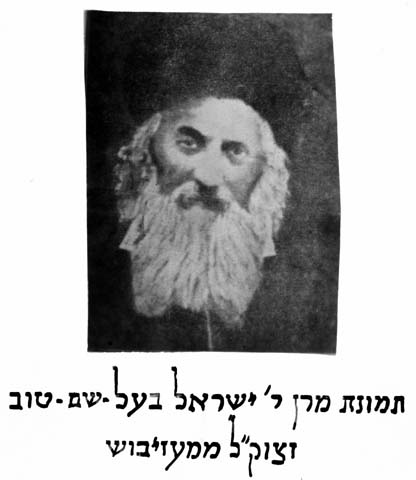

Paul Gass is a descendent of the Ba’al Shem Tov.

Our trip to Ukraine was sparked by my growing interest in family history. My father’s parents came from the shtetls of Turiysk and Kamen Kashirskiy, and my mother and three of her brothers, including Baruch, were born in Novograd Volynsk (known in Yiddish as Zvil). In addition, on the maternal side, I had the good fortune to be born into a rabbinic family, one that traces its roots directly back to the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidic Judaism. The Ba’al Shem Tov’s given name was Yisroel ben Eliezer (Israel, son of Eliezer). He was called the Ba’al Shem Tov–Master of the Good Name–because he emphasized the common good and the need for a positive attitude. Much of the history of the Ba’al Shem Tov and the Hasidim unfolded in my ancestral towns.

IN THE FALL OF 1993, and again in February 1994, Miriam Weiner, a certified genealogist who specializes in Ukrainian-Jewish research, traveled to Ukraine on my behalf. She visited the towns of interest to me and discovered in the regional archives, records of my mother’s family tracing back to the mid-1700s. Miriam also located Baruch’s birth record and was able to obtain an official birth certificate for him. She helped to dispel the myth that all Jewish records were destroyed during the Holocaust. However, the most significant find of Miriam’s journeys was the discovery of living relatives—my mother’s second cousin Paulina and her daughter and family.

After learning about Paulina and reviewing the videos, photographs, and other materials that Miriam brought back for me, I knew had to make the journey myself. I wanted to see what was left of Jewish Ukraine, such as cemeteries and synagogues, and visit in person the remnants of Ukraine Jewry. This urge to walk in the footsteps of my ancestors seems to be inherited—my parents visited Ukraine on their honeymoon in 1937. Remarkably, my newly found cousin Paulina remembered meeting them. She also remembered that my mother’s mother had been killed in a pogrom.

So with Miriam’s assistance and additional logistical support from the Action for Post-Soviet Jewry, I planned my trip and solicited material from friends and relatives to donate to the Jewish communities of Novograd Volynsk and Korets (Korets was the home of my grandmother Gittel and her siblings, and is the place where my mother and her three brothers initially took refuge after Gittel’s murder.)

Learn more about Miriam Weiner

The response to my request was amazing. Sewing materials (cloth, needles, thread, etc.) were donated by Ron Isaacson, Peter Isaacson, Jerry Rogers, Steve Strasner, Alan Getz, and Mike Schwartz. Rosalie Gerut provided Jewish music on audiotapes and CDs. Medical supplies, such as insulin and prescription drugs samples, were contributed by the North Shore Congregation in Glencoe, Illinois and Action for Post-Soviet Jewry. Before I left home I stopped at Costco, the huge discount warehouse, and bought large quantities of over-the-counter- medicines, such as aspirin and other pain relievers. Judaica (prayer books, tallit, yarmulkes, etc.) came from the North Shore Congregation and me. Cash contributions were provided by many members of my family, as well as by the North Shore Congregation, and me.

I filled twenty duffel bags with supplies and on the afternoon of September 18, 1994, I went to Kennedy International Airport in New York to catch a Delta Airlines flight to Warsaw, Poland. I almost missed the plane though, because I couldn’t find my uncle Baruch. We were waiting at two different places in the airport and when we ran into each other by accident we started yelling at each other.

Paul Gass embarking on his trip to Ukraine

Delta Airlines checked our extra baggage at no extra charge after we explained that they were for a humanitarian mission. However the next morning when we switched planes in Warsaw for the flight to Kiev, Ukraine, we had to take a Polish airline. The personnel there wanted to charge us an astronomical fee. Baruch yelled and I bribed, finally settling in cash for a lesser amount. One of the duffel bags contained canned tuna fish and large salamis. A luggage handler helped himself to a salami.

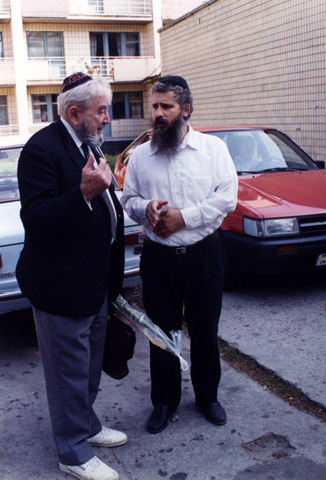

Baruch in conversation with the rabbi who met us at the airport

Baruch refused to walk through the screening machines at airports. When the security personnel insisted, he raised a ruckus, demanding to see the supervisor and telling them he had a pacemaker. He won every time. I have absolutely no knowledge of Baruch ever having heart problems or needing a pacemaker. But he had one or more bullets and pieces of shrapnel in his body that had never been removed. He probably didn’t want to have them set off metal detectors in airports.

Read how Baruch got his bullets

We were met at the Kiev airport by Miriam Weiner’s able assistant, Vitaly Chumak, the mayor of Ataki, a city in Moldova. He served as our guide and translator, and put in many long days on our behalf. I cannot overstate how crucial Vitaly was to the success of our trip.

Vitaly was accompanied by our photographer Dmitry B. Peisakhov of Kiev, and Dmitry’s son, Maxim. Vitaly, Dmitry, and Maxim were our traveling companions for the Ukrainian leg of our trip. We were also greeted at the airport by a rabbi, whose name unfortunately eludes me. That evening Baruch and I attended Sukkot services at the Kiev Synagogue and we spent the night at Hotel “Russ”.

Paulina taking the measure of Paul. Her daughter Fanya is supporting her.

THE NEXT DAY, I met the family members whom Miriam Weiner had discovered in Novograd Volynsk. Miriam had used a 20-year-old phonebook to look up my mother’s family names, Korff and Goldman. There were no Korffs in the phonebook but four Goldmans were listed and one still lived in the town. Miriam struck gold when she phoned the home of Paulina Isakovna Goldman Bortman. Pauline started reeling off her family tree and eventually Miriam determined that Paulina was the second cousin of Adele Korff, my mother. Paulina was quite excited because she knew that a branch of her family lived in America but she had not known how to contact us.

Miriam’s timing was fortuitous. Paulina was ill with cancer and was preparing to move the next week to Kiev where the medical care was better. She had applied for a visa to the United States so she could join her son Isaac Bortman, who had immigrated 15 years earlier and was now living in Trenton, New Jersey. But Paulina’s visa was denied because she was terminally ill.

When I met Paulina face to face I was struck by her uncanny resemblance to my mother, of blessed memory. Paulina was almost a carbon copy both physically and in character. She was very direct and very curious about my life, wanting to know how I was with women. She practically quizzed me on my sex life.

I also met Paulina’s daughter Fanya Skibetyanskaya, an engineer, and her husband Boris Skibtyanskiy, an economist, their daughter Elina, and Elina’s husband Aleksander (Sasha) Kleynerman. Elina is a teacher and Sasha is a doctor. They are the parents of Larina, who was then four years old. Another daughter, Leana, was born a few years later.

Paulina and her family were extremely warm to Baruch and me. They had prepared a huge meal for us and did their best to make us feel welcome. They truly felt like family from the moment we met.

I felt very much at home. I showed photographs of family members, and I brought copies of my mother’s honeymoon pictures from Ukraine. Paulina recognized my parents and elaborated on her memories. They had visited Novograd Volynsk in 1937, a very dangerous time, and they couldn’t hold a large family gathering. My parents could only meet with family members late at night in small groups.

The next morning Baruch decided to visit his good friend, Ambassador Bill Miller, at the American Embassy in Kiev, but hadn’t made arrangements ahead of time. When we showed up at the embassy, the Marine guards wouldn’t admit us because we lacked authorization. The guards explained that the ambassador was busy and couldn’t entertain visitors, but Baruch insisted that they phone the ambassador and announce his arrival. Bill Miller was quite willing to make time to see us but the Marine guards wouldn’t escort us to his office, as we hadn’t been cleared. So the ambassador came down to the entrance to personally escort us.

Left to right, Maxim Peisakhov, Ambassador Bill Miller, Vitaly Chumak, and Baruch Korff

Left to right: Paul Gass, Ambassador Bill Miller, and Baruch Korff

Baruch wanted a photograph of himself with Bill Miller but the guards had confiscated the camera equipment. When the ambassador called down and asked for the camera, we got to witness more bureaucracy in action. The guards said they weren’t authorized to bring the camera up to the office, so the ambassador had to retrieve it himself.

The ambassador and Baruch had a wide-ranging discussion about politics, world events, and lingering antisemitism in Poland and Ukraine. They even discussed the superstitious belief that antisemitism is passed through a mother’s breast milk directly to her child. Additional insight into anti-Jewish sentiment in the region was also gleaned from the members of the U.S. Embassy in Poland whom we visited in Warsaw at the end of our trip.