Continuing the Rabbinic Tradition in America

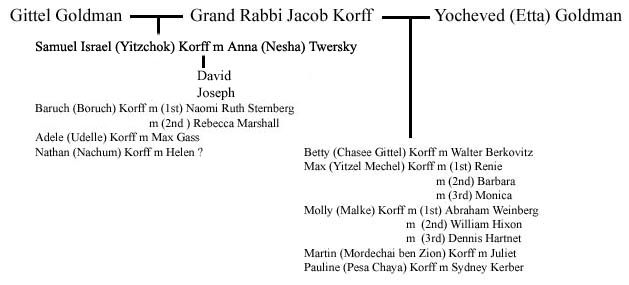

SAMUEL ISRAEL KORFF, THE FIRST OF FOUR CHILDREN of Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff and Gittel Goldman, was born in 1911 in Novograd-Volynsk, Russia (called Zvil by its Jewish population). Known to the family as Yitzchok for his middle name (Israel in English), Samuel witnessed the murder of his mother during a pogrom when he was eight years old.

Samuel Korff (far right) with his father Jacob and younger brother Baruch

SAMUEL KORFF AND HIS SIBLINGS

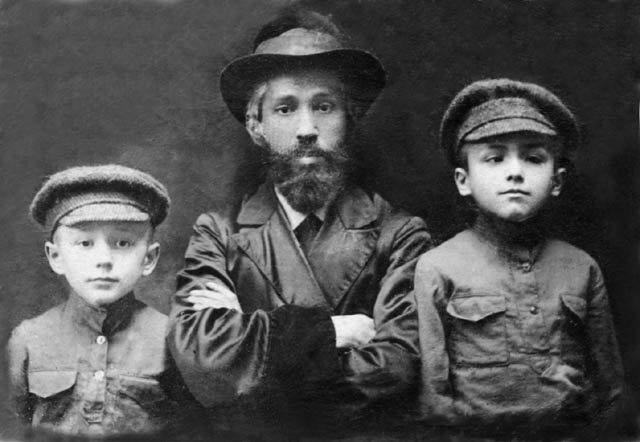

Following tradition, Jacob Korff married his dead wife’s sister, Yochoved (Etta) Goldman, but Samuel and the other children of Gittel never quite accepted Etta as their new mother. They addressed her as “Auntie,” not “mother.” Etta bore Jacob five more children, two of them born in Europe, before the family immigrated to the Unite States. By the time the family settled in their new home in Dorchester, Massachusetts, in 1926, Samuel was 15 years old.

Samuel Korff (back far-right) with his stepmother Etta (center) and siblings (clockwise from Samuel) Adele, Betty, Max, Nathan, and Baruch

Family dynamics are a complicated affair in any family with a stepparent but even more so in an immigrant family. Samuel’s son Joseph Korff lent his perspective to the forces that shaped the relationships between Samuel Korff and his siblings:

“My father worshipped his father. I don’t know whether it was due to a lack of a mother figure. There was sibling rivalry in a chaotic environment. The first four [Gittel’s children] had been more groomed for the position of rabbi and rebbitzen.[1] None of the other children really followed in this path. Perhaps, they were rebelling in their youth. I don’t think my grandfather had strong control over them. They were raised in an American environment as opposed to a European one. There was greater freedom of action. The eldest son in the second group [Max Korff] joined the Navy or was drafted and that brought broadening influences.

“My father was groomed to be the heir and given responsibility. He was supposed to take care of all of his parents’ issues and all of his siblings’ issues—the typical oldest child syndrome. He dealt with doctors, lawyers, and was the peacemaker. My father was my grandfather’s everything. He was viewed by the others as a bit of a father figure without the actual authority of one. So there was tension. Later, after the death of his father-in-law, my father became the patriarch of my mother’s immediate family, too.”

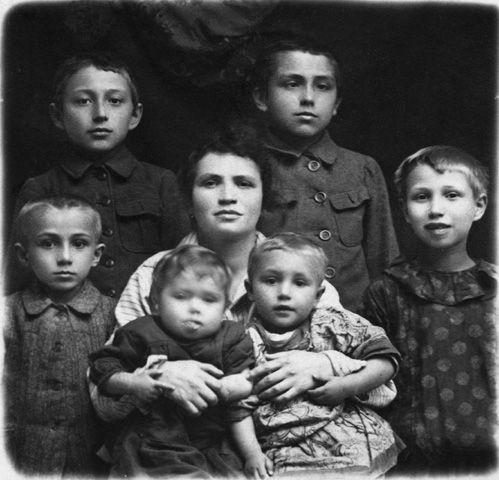

Raised to follow in his father’s footsteps, Samuel left Dorchester for New York City to study for the rabbinate. He graduated from Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Yeshiva, a branch of Yeshiva University, in June 1933, and was ordained with high honors. A year later, he married Nesha (Anna) Twersky, the daughter of Rabbi Nachum and Malcha Twersky.

Samuel Korff and Nesha Twersky

Nesha Twersky Korff recalled her courtship with Samuel Korff:

“My husband used to go to the yeshiva not far from where we lived. He used to come to us for Shabbos. I don’t know why he liked me. So one day, he said Nesha, I want you to marry me. So I said to myself, If you like him… So we saw each for two years. He was a year younger than me.[2] If I didn’t like him, I wouldn’t have married him. He was honest, sincere. He was trustworthy, good-natured. We married on June 19, 1934, in Brooklyn.”

Nesha was a good match for the young rabbi. Like Samuel, she came from a respected rabbinic line; her father, Rabbi Nachum Twersky, was a direct descendant of the Ba’al Shem Tov. Also like Samuel, she had lost her mother, Malcha, when she was young. So she understood what it was like to be an orphan. Nesha remembered:

“We lived in Kishinev–my father, my two brothers, and a sister…There was a fire in the shul. By the time my mother ran out the smoke had damaged her lungs. My older brother, too, damaged his lungs. My mother went to a sanitarium but they couldn’t cure her and she died. My brother died, too. I don’t remember my mother. There weren’t any pictures. I never knew what she looked like. The people who knew her told me my mother was a beautiful woman. Do you know what it is like never to have a mother? Never to know a mother’s love?”

Also like Samuel, Nesha had to deal with a new stepmother and a new home in a distant land. Her father remarried a rabbi’s daughter, and subsequently the family moved to the United States.

“If it were not for my stepmother’s parents we would have been killed in the Holocaust. Her parents came to the United States and brought her and our family over. I was about 15 years old. We settled in New York.”[3]

But all was not milk and honey in the Promised Land. According to Nesha:

“My father was very good to us but he couldn’t get along with [his new wife]. They had fights. Sometimes my father would send us children some place nice on vacation in the summertime, and she would be jealous. Her mother used to come in and got mad at my father. She didn’t think he did enough for her daughter. She would say, Did you lose a lot of strength on my daughter? And he would reply, Did you lose a lot of strength on my children? My stepmother never had any children of her own.”

Nesha’s marriage to Samuel Korff gave them both the opportunity to make a happier home for themselves. The newlyweds remained in New York for two years, during which time their elder son, David was born.[4] Soon after the baby arrived, Samuel received a job offer in Boston and the couple pulled up roots to move to New England. Leaving her family in New York was difficult for Nesha, but her husband’s future was her first consideration.

“I didn’t want to move to Boston,” Nesha remembered, “but my husband got a position in Boston. I didn’t want to leave my father. David was about 7 months old, so my father came with me when we moved and stayed for four or five days while I got settled.”

Samuel and Nesha rented an apartment for $40 a month at 1238 Blue Hill Avenue in Mattapan, a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, close to Dorchester where Samuel’s family lived. After Samuel and Nesha’s younger son, Joseph, was born, they decided it was time to move to a nicer place.

Nesha with David outside their apartment in Mattapan

“We wanted to buy a house in Mattapan at 573 Norfolk Street,” said Nesha. “It was an old house and there was a lot of remodeling to do in it. But it was a spacious twelve-room home and there was a beautiful lawn in front. There were three rooms on the top floor. We had to build several steps so the people could walk up. It was like an apartment.

“My husband needed a mortgage. He went to a man, a very nice man, who knew my husband very well. The man went to a [non-kosher] restaurant and he wanted my husband to go in with him. My husband said, No, I can’t go in there. I’ll wait outside. So after he came out the man said, Rabbi Korff, now I can trust you, since you didn’t want to go in there because it is not kosher. Now I can see you are a reliable person.”

A LONG AND HONORABLE CAREER

ONCE BACK IN BOSTON, Sam continued the rabbinic tradition of his forebears, but expanded it to encompass a broader scope. Not the kind of man to sit in his father’s shadow, Sam had broader ambitions for himself and he had a love-hate relationship with the role of rebbe as it was evolving in the Boston community and in other Hasidic communities in America.

Joseph Korff expounded on his father’s career:

“There are Hasidic dynasties that are in effect the government for their people, even in America. They provide social support, educational support, and help the community interrelate with the secular world. Their role is to further tradition and provide social resources supplementing and complementing those available from the government. There are heirs to this tradition and my father respected them. However, my father couldn’t have gone that route. The Hasidic community in Boston was a relatively small one and wouldn’t have supported him financially. He didn’t want to subsist on people’s donations. More importantly, the Hasidic community wasn’t large enough to deal with my father’s goals and ambitions.”

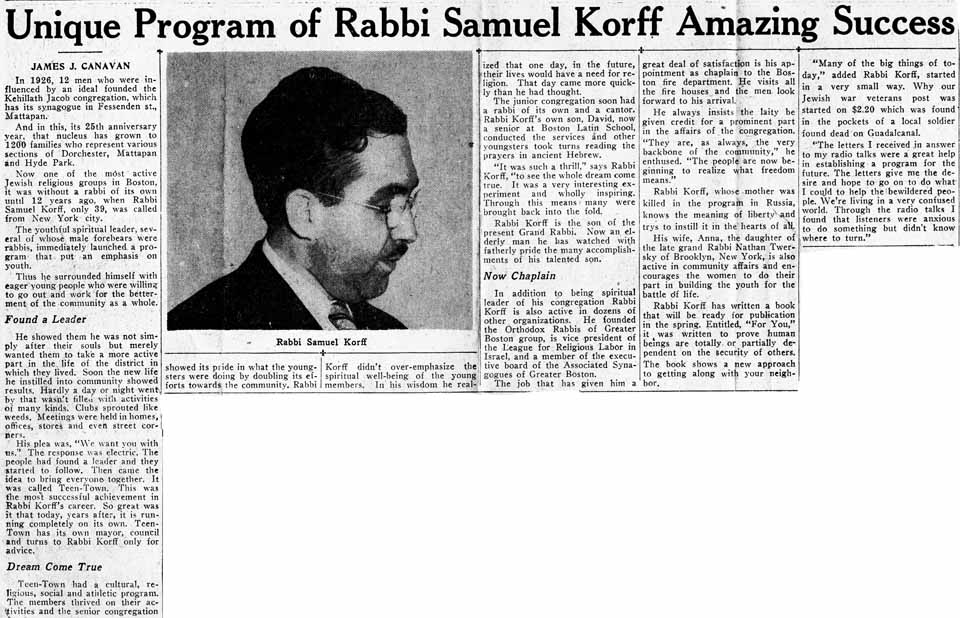

In 1938, Samuel Korff became the spiritual leader of Congregation Kehillath Jacob, an Orthodox synagogue on 18 Fessenden Street in Mattapan. He built up the membership to over 800 families and the congregation became one of the most influential in the area. An article in the Jewish Advocate published in 1958, captures the essence of Samuel Korff’s tenure at Kehillath Jacob:

“…Rabbi Korff has followed one line of dedication; he has brought godliness down from the pulpit and into the homes, lives, and very souls of those he has taught, and those who have learned from him without the knowledge that they were learning. His love of young people and understanding of their special needs became apparent to his congregation very early in his career.

“In 1938, then only twenty-four years old, Rabbi Korff was called to Kehillath Jacob. We want you with us, he told his young people, and being wanted, they came.

“This was not a job to be done through preaching alone, so Rabbi Korff came down from the pulpit. I set out to mingle with the young people, he says. I learned to understand their problems and their needs. They came to me with their troubles. My home became a gathering place for the youth.

“He set out to found a junior congregation. He founded lecture groups, social clubs, basketball teams—groups for different age levels from nine to twenty-five years of age. The plan was to take the young people from the periphery of religious life and make them the center of all its activity. It was to found a youth movement compounded of all the facets of community life; athletics, social welfare work, religious culture, and social life. It was to make youth important in religion and thus make religion important in youth.

“When the JAPS bombed Pearl Harbor and America went to war, Rabbi Korff’s youth movement was beginning to grow and prosper. The war punctuated the movement’s first phase. The members of his youth movement were scattered on battlefields all over the world. Yet, the work had not been in vain. Letters came in from Anzio, or Saint Lo, assuring the rabbi that the young people had not forgotten his ideal. Before World War II was ended, Rabbi Korff had already organized the first World War II Jewish War Veterans Post in the Commonwealth.

“Meanwhile the activities of the youth movement [had] been carried on by those too young to enter the armed forces. For them, Rabbi Korff founded ‘Teen-Town,’ a youth metropolis that enrolled almost 800 young people of all ages, divided into separate groups for special interests of activity. He then inaugurated a campaign for a community center and a Hebrew School building. The congregation expanded. New members swelled its ranks. Young adult and adult groups flocked to the portals of Kehillath Jacob and its institute of religious study. The slogan was Make Kehillath Jacob a place for every member of the family.” [5]

Samuel Korff in the wedding processional of one of his sisters. His father, Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff, can be seen in the background accompanying the bride down the aisle.

THE ASSOCIATED SYNAGOGUES OF NEW ENGLAND

Samuel Korff’s role was not limited to congregational rabbi. According to Joseph Korff:

“My father was one of the founders of the Associated Synagogues of Massachusetts, which later became the Associated Synagogues of New England. The organization represents all branches of Judaism in service to the New England Jewish community.

“The Orthodox tend not to join organizations like the Associated Synagogues, but his colleague Rabbi Mordechai Savitsky [spiritual leader of Congregation Chevra Shas in Dorchester] encouraged my father to become a member of the Vaad Harabonim, which was part of the Orthodox wing.[6] Savitsky and my father had a falling out and Savitsky dropped out of the Vaad. My father became the rabbinic administrator of the Associated Synagogues, a role which was akin to executive director. He ultimately built the organization into the Associated Synagogues of New England.

“Some members of the Orthodox community castigated my father for being associated with an organization affiliated with Conservative and Reform Jews, but he got concessions from these groups. One was that within the Associated Synagogues the Vaad would be the functioning rabbinic court and it would be controlled by the Orthodox.

“My father also wanted to centralize kashrut [7] certification so that observant Jews throughout the area could be certain that Jewish dietary laws had been observed in food preparation. He got all the synagogues and temples in the area to agree that they would admit only those kosher caterers certified by the Vaad Harbonim. This centralized kashrut for all of Massachusetts and later, New England. This was a major coup but it led to some friction because some of the Orthodox rabbinate wanted to have the income generated from supervising kashrut. So they tried to attack my father. Through the Associated Synagogues, however, my father had sufficient leverage to carry out his goal. He later advanced this program by establishing an extension program to certify packaged food as kosher.”

Unidentified ceremonial function. Samuel Korff is the sixth from the right; his brother Baruch is the fourth.

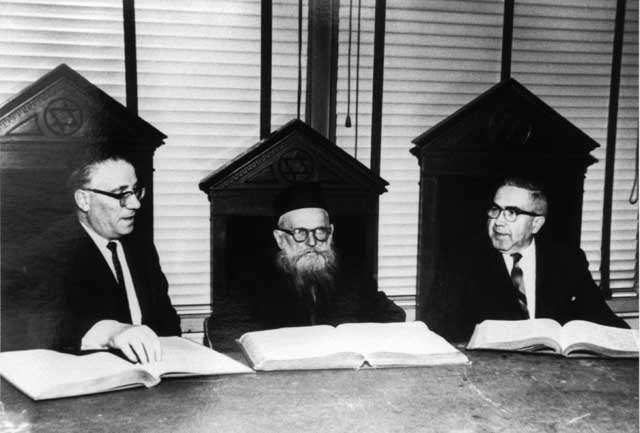

THE BET DIN

Samuel Korff served on the Bet Din, the rabbinic court in Boston.

“My father was also a driving force behind the Bet Din, the rabbinical court of justice of the Associated Synagogues,” explained Joseph Korff. “Almost every city has a rabbinical court. The courts tend to be formed by Orthodox rabbis and they deal with religious questions and grant religious divorces. Their focus tends to be supervision of kashrut and Jewish family law. My father, however, broadened the scope of the Bet Din.

An article in the New York Times in February 1973, described the uniqueness of Samuel Korff’s Bet Din:

“…until the late 18th and 19th centuries, when Jews began leaving the ghetto. The beth din (house of law) ruled on virtually all legal matters within the autonomous Jewish communities. Then gradually the courts lost their secular legal standing and narrowed their scope to ritual and family matters.

“Today most rabbinic courts…focus on such cases as marriage, divorce, and conversion. But the Massachusetts Rabbinical Court of Justice, of which Rabbi Korff is administrator, is no ordinary beth din.

“Ever since the socially conscious 1960s, the 31-year-old court here has gotten involved in social issues, often outside the Jewish community…. [It] has even settled disputes between gentiles. It tackles issues upon request from individuals or groups and charges no fee. If both parties in a case sign over rights to the court as an arbitration board, the decision is legally binding. Otherwise, the beth din’s only enforcement power is “moral persuasion” or public pressure within the Jewish community.

“…From the beginning the Massachusetts court has represented all three branches of Judaism, unlike the other courts around the country, most of which are Orthodox. This arrangement, according to Rabbi Korff, is not problematic.

“When it is asked to judge ritual divorce or other cases that directly involve halacha (Jewish law) only Orthodox authorities sit on the court since neither Conservative or Reform branches observes halacha strictly…Other issues…may be settled by rabbis of any branch, as well as by lay people–lawyers, political scientists, and other experts in various fields—who may or may not be Jewish. But in such cases, the panel does not constitute a beth din in the traditional sense of the word.

“All persons sitting as judges on a given case have equal votes in its outcome. The majority decision prevails; rabbinical courts do not issue dissenting opinions…

“As administrator [Rabbi Korff channeled] discussion to basic issues, interrupting what he thought to be extraneous dialogue and drawing conclusions when it seemed that all views have been expression.

Samuel Korff at a meeting of Boston’s Bet Din

“He also softened questions by his colleagues to spare the feelings of witnesses. For example, in a case involving a Greek woman who wished to become an Orthodox Jew, Rabbi Korff interrupted a colleague who was asking her what she would do if she broke up with her Jewish fiancé.

“I wouldn’t be that cruel, Rabbi Korff said smiling to the young woman, I would ask if you want to become Jewish irrespective of your status, married or not married.

“…According to the 59 year-old rabbi, a beth din can offer nonsectarian resolutions to all human problems because its concern is justice andjustice must transcend a given creed, race, or religion.

“For instance, he said, a tenant leases an apartment and then discovers it has cracks in the wall and holes in the floor. He had already signed a contract, so who is liable?

“Jewish law says the landlord must make every repair, Rabbi Korff concluded. Why? Because no one has the right to sell something that is a receptacle for human misery. So it was safe for the tenant to assume the landlord would be a mensch [a good human being].

“…Responding to a request by students and faculty at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the court in 1970 issued a 54-page document exploring matters of conscience.

“Among other things it supported selective conscientious objection—objection that is to one war, but not all wars—but declined to rule on the legality of the Vietnam War because it had not heard government testimony.

“Although some Orthodox rabbis take a dim view of a beth din that tackles such problems, Rabbi Korff is optimistic that other rabbinic courts will widen their focus of concern soon.

“If the rabbinic court would be restored to its proper position, the rabbi asserted, it would bring a voice on conscience not only to the Jewish community but to the total society.” [8]

JOSEPH KORFF EXPLAINED his father’s dedication to the Bet Din:

“My father took the most pride in the things he got involved with during the mid-to-late 1960s and early 1970s. As the driving force behind the Bet Din, he led a precedence-setting settlement in a landlord-tenant dispute. It started with Israel Mindick and his brothers, Joseph and Raphael, Jewish landlords who were having a dispute with their minority tenants in Boston’s South End. The Mindicks were the largest landlords in the South End and they consistently refused to make repairs on their properties. Rabbi Judea Miller, a Reform rabbi from Malden connected with the Civil Rights movement, learned that the Mindicks’ Black and Hispanic tenants planned to picket the Mindicks’ Orthodox synagogue. By promising to participate in the protest, Miller was able to convince the demonstrators to picket in front of Israel Mindick’s home instead of the synagogue.

“Miller approached my father, explained that the landlords were creating an interfaith disaster, and asked him to conduct a Bet Din. My father wasn’t convinced that this was a Jewish issue. Then Miller revealed that the Mindicks had set up dummy corporations and named them for the words in the final verse of Psalm 19: Yihiyu, Leratzon, Inrei, Fee, Vehegyon, Leebee, Lifaneha, Hashem, Tzuri, Vigoali (May the words of my mouth and the meditations of my heart be acceptable before You, O Lord, my rock and my redeemer.) My father agreed to take the case and the tenants agreed to argue their case in my father’s court. The Mindicks reluctantly agreed to appear, for to be in contempt of the Bet Din meant shunning by the Orthodox community.

“The ruling favored the tenants in general, and it was binding arbitration. My father’s example was credited as a key factor in the establishment of the Boston Housing Court. This case achieved nationwide attention and was reported in the Wall Street Journal and other places.

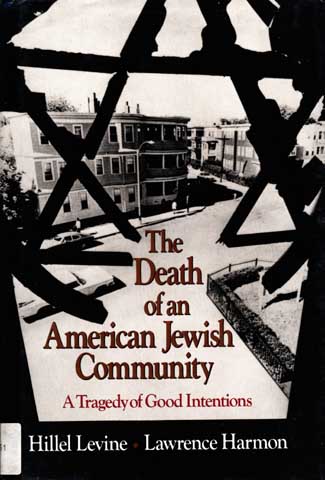

In the book The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions,authors Hillel Levine and Lawrence Harmon described the rabbinic court proceedings:

“For the better part of the summer, the rabbis heard testimony from the tenants and landlords…The tenants recited familiar ills of exorbitant rents paid for substandard dwellings crawling with rats and roaches. The Mindicks countered that they could hardly be expected to take responsibility for tenants who threw garbage out of windows and damaged apartments faster than one could hope to repair them…

“Rabbi Korff never directly criticized the landlords, preferring instead to work through parable. A rabbi approached the door of wealthy man to seek a charitable donation, he told the Mindicks. The wealthy man’s servant announced the rabbi and invited him inside. The rabbi, however, explained he would wait on the doorstep. The servant insisted that the rabbi come out of the cold, but the rabbi would not budge. Soon the wealthy man himself approached the rabbi and beseeched him to come inside for refreshment. ‘No,’ the rabbi insisted. ‘You come outside. I want you to know what it feels like.’ Israel Mindick suffered the long sermons in silence. Often, however, his lawyer would complain of the length of the proceedings. But Korff quickly quieted him, explaining that, there are times when divine providence requires great sacrifice.

“…The arbitration of social problems through ancient religious laws was unprecedented. National magazines and newspapers shared that view. On…the day scheduled for a final agreement between Mindick and his tenants, reporters from The Wall Street Journal, Look Magazine, and scores of others were on hand. The final agreement offered concessions to both tenants and landlords. The landlords agreed to repair, maintain, and paint the apartments in accordance with city codes. They also promised to provide adequate heat and hot water, daily janitorial service, more trashcans, and locks on all hallway entrances. The tenants, in turn, signed a pledge to help maintain the properties once repairs were in place and to drop their demands for private security guards at each building. The contract further stipulated a five-member board of arbitration to settle questions of overdue rents and other disputed claims…

“Suddenly a unique approach had been found for the seemingly intractable problems between Jewish landlords and black tenants…”[9]

Samuel Korff used the Bet Din to settle an ugly dispute between black tenants and Jewish landlords.

Leonard Fein, a Brandeis University professor, described what took place the day the formal agreement was signed:

“The slum landlord in question, in a last burst of the self-pity which had marked his stance through much of the negotiation, pleaded to several of us that he was about to sign himself into bankruptcy. Why, he said, am I being penalized? All I’ve wanted was to put away a few dollars for my children. Is that so wrong?

“To which he was given the traditional answer, in the form of a question: What is more important, money or a good name? To this question, an observant Jew—and it was the fact that the man in question was an observant Jew that had made the entire proceedings possible—knows the answer. With an air of resignation, he signed the document–and truth to tell, there was a fair chance that he was, in fact, agreeing to bankrupt himself.

“When Rabbi Korff stood before the cameras to announce the agreement, he thanked the several people who had helped to engineer it. And then much to the surprise of those of us on the ‘inside,’ who had over the months become increasingly annoyed with the landlord, the good rabbi went on: In the end, he said, the fact that we have been able to bring these negotiations to a successful conclusion has been due to the extraordinarily sensitive and gentlemanly behavior of one man, a real prince among men, a decent and devoted and generous man, and one who deserves to be so recognized. I refer here to Mr. X (the landlord) [sic].

“I was stunned. Whatever one might have said about Mr. X. generosity of spirit was not his long suit, nor special sensitivity. I had not understood what Rabbi Korff had understood. He was giving Mr. X the good name he had promised him. It was a kind and decent thing to do.” [10]

Despite, Rabbi Korff’s phenomenal skill in obtaining such an unprecedented court ruling, the Mindicks made few improvements to their properties. According to Hillel Levine and Lawrence Harmon:

“Tenants in twenty of the brothers’ buildings went on a rent strike that winter, charging that the landlords had failed to live up to the terms of the rabbinic court’s agreement. The rabbis concurred and slapped the Mindicks with a $48,000 fine to be distributed among the affected tenants…The Mindicks sold off thirty-four of their buildings to the Boston Redevelopment Authority, which placed them under the control of the South End Tenants Council for management and repair. The price of doing business in Boston, at least as far as the Mindicks were concerned, was growing much too steep.”[11]

Joseph Korff described other ways in which Rabbi Samuel Korff influenced the rabbinical court:

“My father also guided the Bet Din in other areas not typically associated with rabbinical courts. This included an opinion by the Bet Dinconcerning the circumstances under which conscientious objection was permissible under Jewish Law. My father had been fairly active with the Hillel communities in the local colleges; one of his motivations was that he was interested in avoiding assimilation, intermarriage, and loss of Jewish identity. When the question came up about the role of conscientious objection in the Jewish religion, which was a very hot topic during the Vietnam War, he convened scholars and wrote a paper on conscientious objection and its role in Jewish philosophy. He built up a whole responsa showing why it was acceptable within Jewish philosophy. He received a decent amount of publicity, and positive feedback from the students.

“After that he was asked to deal with kashrut and health safety issues. He wrote a responsa on that. This included an opinion by the court concerning health standards in food preparation required by Orthodox rules.

“He constantly reached out to the Hillels[12] of the various colleges and supported them. He attempted to bring the religious principles with which he was imbued to a meaningful level within the Jewish college community which was composed of people from many different kinds of Jewish backgrounds.”

THE SECULAR COMMUNITY

RABBI SAMUEL KORFF FUNCTIONED as well within the secular, non-Jewish community as he did in the Jewish community, combining Jewish scholarship with political savvy. He was vigilant in his fight against anti-Semitism, which was never far from the surface in largely Catholic Boston. In the 1940s, this hatred was fueled by Father Leonard Feeney, a rabidly anti-Semitic priest who vilified Jews in sermons delivered on the Boston Common.

An article in the Jewish Advocate published in 1958, described how Rabbi Korff handled the rise of anti-Semitism in his community:

“In 1941…a wave of anti-Semitic incidents [inundated the Dorchester-Mattapan area]…Throwing the force of his small frame against lethargic officials, Rabbi Korff asked for the safeguarding of those principles without which this nation could not exist. Everyone is responsibility if he is indifferent to the situation.

“Rabbi Korff was never indifferent to any situation which threatened the well-being of his community…He organized a Good Neighbor Association ‘for the purpose of promoting and fostering mutual understanding, friendship, and cooperation among the inhabitants of communities regardless of race, color, or creed.’

“On $2.50 found in a dead soldier’s pocket on Guadalcanal, the first war casualty from his neighborhood, he consolidated the group into a living force for democracy. [In 1944] he was instrumental in bringing about the Good Neighbor Conference on Anti-Semitism [a symposium for leaders of all faiths.]”[13]

In November 1943, Rabbi Korff addressed the Religion and Labor Foundation Conference at the CIO convention in Philadelphia. (The CIO was a labor union, which joined with the AFL to form the AFL-CIO.) Among the foundations’ representatives were delegates from 30 theological seminaries. Rabbi Korff led a panel on church and labor and their roles in promoting racial unity in the post-war world.

Samuel Korff’s outreach to the secular community manifested itself in other ways. According to Joseph Korff:

“During the Hitler era, my father [like his brother Baruch] was active politically promoting Jewish causes and getting people out of Europe, but he did this quietly.

“After my grandfather’s death, my father picked up his political contacts with John W. McCormick the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives [for whom Baruch was a speech writer] and other leaders. When I was doing a political science project at Brandeis, he set up an appointment with McCormick for me.

“In 1947, Mayor James Michael Curley appointed my father as the first Jewish chaplain of the Boston Fire Department. This was a position he held until his death. I think it happened because my father built up his role as administrator of the Associated Synagogues to function with the political community of Boston. If someone had a Jewish question who did they call? The Associated Synagogues. And who do they get? Rabbi Korff.

Samuel Korff on the job as Jewish chaplain of the Boston Fire Department

“In the early years he went to fires. He had a chauffeur who drove him around in his official fire department car. Occasionally when I was late for school I got a ride in it. My father administered to the few fire fighters who were members of the Jewish faith. I can remember fire fighters coming to the house for counseling; this was part of the chaplain’s function. He would represent the Jewish faith at organized functions at which someone was required. Later in his life, he also served as Jewish chaplain at Deer Island House of Corrections.

Despite his hectic schedule, Samuel Korff made time for his sister Adele and her husband Max Gass. Samuel and Nesha celebrating a happy occasion with his sister Adele and her husband Max’s family.

Left to right: Minnie & Joe Alter; Ida, Jonas & July Ullian; Max, Janet & Adele Gass. Sam & Nesha, Shiela & Sam Fish

“My father could have played a larger role on the national Orthodox stage, but he had too many things going locally to find time for that. He did not have rich donors, which may have sustained prior generations of rabbis in their public endeavors, and the need to keep his family in a middle-class lifestyle, may have precluded his entry into the national arena. However, for many years my father did conduct weekly radio programs over CBS, lecturing on topics of Jewish interest.”

PUBLIC TRIBUTE

In May 1958, Congregation Kehillath Jacob paid tribute to Rabbi Samuel Korff in honor of the 25th anniversary of his ordination and in recognition of 20 years of distinguished spiritual leadership to their congregation. One thousand people paid their respects, including congregants of all ages and leading rabbinic, civic, and national figures. A book of tribute was prepared documenting Rabbi Korff’s service to the general community and to his own congregation. The festivities were capped with a testimonial dinner at the Lampert Auditorium in the Kehillath Jacob Hebrew School, where the congregation awarded Samuel Korff with a lifetime contract.

Booklet prepared for the testimonial dinner

Hundreds of congratulatory messages were sent from leading local and national leaders, including Governor Foster Furcolo of Massachusetts, Congressman John W. McCormick, U.S. Senator Leverett Saltonstall, U.S. Attorney General George Finegold, Rabbi and Mrs. Joseph Soloveitchik, Rabbi Moses Soloveitchik and U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy.

David Korff (center) speaking at the testimonial dinner honoring his father in 1958. Sitting to the to the left of David is his wife Harriet; to the right of David is Samuel Korff. Samuel’s brother Baruch is standing next to him.

A write up preceding the ceremony appeared in the Jewish Advocate on April 24, 1958. In it Rabbi Korff was described as

“…a very human man of rich humor, a quick smile, a radiant personality, and a dangerous persuasion to defend the underdog. This sense of justice in a world where justice is [not always supreme] is not his most fortunate characteristic. It is, however, his most endearing.”[14]

REDLINING AND THE DISPLACEMENT OF THE JEWISH COMMUNITY OF DORCHESTER, ROXBURY, AND MATTAPAN

IN 1967, IN THE SPIRIT OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, many of Boston’s politicians, bankers, philanthropists, and religious leaders decided to expand home ownership opportunities for Blacks and integrate Boston’s segregated middle-class neighborhoods by making mortgages loans available to minorities, often with no money down. However, because Jewish organizations were active in the Civil Rights movement in official and unofficial capacities, and because Jews were perceived as being more tolerant than their Irish or Italian counterparts, a private agreement was reached among the bankers and politicians to make the loans available only in Boston’s Jewish neighborhoods. The Yankee bankers may also have been motivated by a heavy dose of anti-Semitism and greed. Many of the residents in the Jewish neighborhoods had paid off their mortgages so the area was unprofitable for them.

The resulting policy, known as “redlining,” boomeranged. Instead of peacefully integrating the Jewish neighborhoods, chaos reigned when increased integration brought a dramatic rise in crime. Jews began to move out, their flight hastened by panic-selling and unscrupulous real estate brokers engaging in blockbusting tactics. With a large Black population competing for a piece of the American Dream, and a limited area in which to find it, there was no lack of buyers.

Joseph Korff remembered this time:

“The banks were trying to take a position that would be useful from a public relations vantage point, so they agreed to provide federally-insured housing loans on a lower-than-usual underwriting standard. This policy allowed minority people to get loans that they normally would not have gotten. The banks got together and defined a neighborhood within which the loans would be granted. The area the banks defined was just precisely the Jewish neighborhoods of Mattapan, Roxbury, and Dorchester, home to 90,000 Jews.

“Blockbusters came and they blockbusted. My father fought Jewish flight. He went to various Jewish organizations, he dealt with the politicians, but it all happened very rapidly, within a two to three year time period. My father did what he could to stop it.

“Redlining greatly accelerated Jewish migration to the suburbs. In the normal pattern, immigrants settled in Roxbury. Then they stepped up a little in affluence and moved to Dorchester, but they were still basically lower middle class to middle class. When things got better, they moved to Mattapan and they started to sprout. When the wealth came in, they moved to Brookline and Newton. So it was a natural migration anyway. But the migration became extremely accelerated because of the redlining and subsequent violence. There were gangs that beat up Jewish children. The elderly became frequent targets of muggers.

“The Jewish power bases of wealth were allowing the redlining in communities where they no longer lived. The Combined Jewish Philanthropies permitted redlining to happen and may even have encouraged it. Many Jews and Blacks had worked extensively to foster integration. They did not take an active stand or delve deeply enough to understand that the Jewish neighborhoods were going to be decimated. The redlining and the lower underwriting standards when coupled with the activities of the blockbusters had the effect, however, of maintaining segregated communities. Legislation was subsequently passed, but it passed too late.

“My father would come home thoroughly frustrated and the stories would abound about the people getting calls from blockbusters. He would talk to his parishioners and tell them, Don’t move, it’s okay, we’ll do something, and they would come back with stories about this one being mugged and that one being mugged and the broker saying a Black was moving in next door. Some of it was true, some of this wasn’t true but it was totally exaggerated by unscrupulous real estate brokers coming in and profiting on the buying and selling. They would encourage Jews to sell their homes at below-market value to them and then the brokers would turn around and resell the houses at inflated prices to Blacks.

“My father was one of the last Jews left in Mattapan. My mother was mugged twice. After the first time my father still wanted to stay. After the second time he decided it was time to go.”

In addition to his wife’s muggings, two other traumatic events contributed greatly to Rabbi Samuel Korff’s decision to leave Dorchester. Both are described in Levine and Harmon’s book.

“…[In May 1971] thieves had broken into [Rabbi Korff’s] Norfolk Street home while he was out on a condolence call. He’d returned to find his front door smashed in and his possessions strewn about his house. Valuable silver and other expensive items that had been in the Korff family for generations had been stolen, but it was in Korff’s study that the greatest damage had been done. My most sacred documents have been destroyed, the rabbi told police. Sacred documents.“

Samuel and Nesha Korff in happier times

“…In March 1973, Rabbi Samuel Korff would deliver the ultimate requiem for Jewish Mattapan. Although most of his congregants had been relocated to other neighborhoods…a handful of congregants at Kehillath Jacob had refused to leave. One congregant, a retired fruit dealer named Charles Shumrack, had repeatedly sought reassurance from Korff. I hope the synagogue will remain open, Shumrack would tell his spiritual mentor after every morning service. It will as long as you are alive and come to synagogue, Rabbi Korff would tell him. Content, Shumrack would embrace the rabbi and walk back across the street to his apartment, where he lived alone since the death of his wife two years earlier. In mid-March, Shumrack was found murdered in his first-floor apartment. His rooms had been ransacked, and his clothes were strewn across the backyard. In his eulogy for Shumrack, Korff unleashed months of pent-up frustration and anger: In days of old, when a murder was committed, the civil and religious authorities, the elders and the judges, before even searching for the criminal who perpetuated the crime, would reevaluate their own deeds, and in a special ceremony would seek to know if ‘our hands did not spill this blood.’ Korff then challenged future historians to determine how it is possible for a Jewish community of 40,000 souls to be emptied in the course of two years and how so much crime was concentrated in the short space of 40 blocks. Resorting to the language of the European Holocaust, Korff further demanded an explanation as to how Mattapan, like Roxbury and Dorchester before it, had become Judenrein.[15] For Korff, the battle was over. He left Boston and prepared to rebuild a congregation in the western suburb of Newton. The only question was whether Shumrack would be the last Jewish casualty.”[16]

Nesha remembered the move to Newton:

“We left Mattapan because a lot of the colored people moved in and they started to fight with the Jewish kids. So the people could not take it. They started moving out. They moved to different places and there was nobody left to go to shul so the shul fell apart. Some people who had moved from Mattapan to Randolph became connected to a synagogue in Randolph that absorbed the name of our synagogue and its memorial plagues.”

Starting over in a new area was not easy for the 60+-year-old rabbi, but Rabbi Korff began a new congregation in Newton, albeit much smaller than his last. He also established the Institute for Religious and Social Studies which brought together experts in various fields for lectures and discussions. He continued to serve the Jewish community in his many other roles, and despite his many responsibilities he found time to privately counsel troubled members in his congregation and work with students directly and indirectly in various area colleges.

Samuel and Nesha Korff (left) at a family dinner with his sister and brother-in-law, Adele and Max Gass (right)

SAMUEL KORFF AS FAMILY MAN

Samuel and Nesha Korff with their children David (the older child) and Joseph (the younger)

JOSEPH KORFF PROVIDED INSIGHT into the private life of Samuel Korff:

“My father loved his father and looked up to him. Following in his footsteps was clearly the life my father chose. My father was under a lot of tension. He became emotionally exhausted in the late forties and went down to Florida for a few months to recuperate. [17]I often wondered if my father had been brought up in a different background what he would have done. He was intellectually gifted but not a scholar along the lines of a Soloveitchik. But his focus was not in developing a following like Soloveitchik.[17]

Joseph Korff

“I saw my father fleetingly. We had dinners together on the holidays and Shabbos but he would go right to sleep after Friday night dinner, exhausted, and he would take a nap on Saturday. We had occasional Sunday trips. From time to time we’d go to New York for a long weekend. Occasionally on a Sunday we would drive to Milton to get an ice cream in the Blue Hills. Despite the fact that we didn’t spend all that much time together, I never felt disconnected.

“I couldn’t go to movies on Saturday and I was big into movies and television. I felt these strains and I didn’t like it, but it didn’t matter very much to me. It may have mattered more to my brother.

“When I was growing up I went to Maimonides, a Hebrew Day School. My friends were not necessarily from our Jewish neighborhood. We lived on the border of a blue-collar ethnic neighborhood and I hung out with guys from this ethnic neighborhood at the playground. I played ball and did what kids do at a playground. My brother was into math and into gambling. So I picked up some of this. Once my father came to the playground looking for me right before a Sabbath or a holiday. He caught me playing cards in the open, and he was furious with me. I hid in the bathroom, blockading the door.

Joseph Korff standing behind his mother, Nesha

Nesha and Joseph Korff (right) with Sam’s sister Adele Gass and her son Paul

Samuel Korff, directly to the right of the bride (his sister Betty

Korff Berkowitz) watches a father-daughter wedding dance, Hasidic style.“My father tried to be what he understood to be a good father. If I wanted a train set, he bought me a train set. He took me to sporting events but he didn’t have a clue as to what was going on. He didn’t know when he was supposed to cheer and when he wasn’t supposed to cheer. He was in there cheering. I could tell it was an act, but it was fine. He tried to tutor me in my Hebraic studies where I was performing below his expectations. This wasn’t always a successful experience because I really didn’t want to do it, and he was exhausted from the week’s endeavors. It was a strain on him.

“My father was very upset that my brother, the older son, didn’t want to follow in his footsteps. There were fights about it in the family. David was extremely bright. He refused to become a rabbi and started screwing up at Harvard. He went through psychological counseling. My father backed off and my brother became a physicist.[18] I never got pressured.

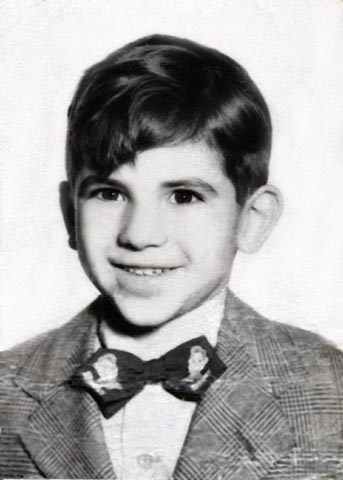

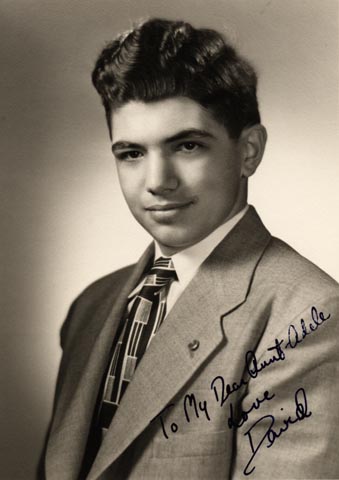

As a young man, David Korff butted heads with his father over career choice.

“I had great respect and love for my father, but I watched various situations he had to deal with–from the members of the congregation who were a power base in their own right and gave him pain and all sorts of grief to when I registered at Brandeis University and he had to deal with Jews who were anti-religious. When class registration fell on a Saturday or a Jewish holiday, he came with me to try to arrange an alternate approach. There was an anti-religious Jew who was in charge and he gave my father and me a hard time. My father just did the Jewish analogy to the Black “Yes-massuh shuffle,” and I was furious. I couldn’t go into this rabbinic life if I was going to end up having to bow and scrape from time to time as I felt he had to. He never pushed me to become a rabbi, and I never had any desire to become one.

“In the late 1950s or perhaps early 1960s, my father suffered a stroke at a Friday evening meal. Had I not been there he probably would’ve died. Somebody had written something accusatory about my uncle, Baruch, in a letter and my father was looking at the letter and talking. He was eating fast which was one of his patterns of behavior. Suddenly, his head just dropped and he collapsed on the table. He had meat stuck in his throat. It was scary. He had an aneurysm that burst. But he recovered.

“My father was called upon to supervise food preparation on the Cunard Lines trips to Israel to celebrate Israel’s 25th anniversary in 1972-73. He really got a lot of pleasure out of that but given the threats of bombing there weren’t very many people on board. The family went, and I got involved in supervising as well. The ship was escorted out of London Bay by frogmen who checked to see if there were any bombs.

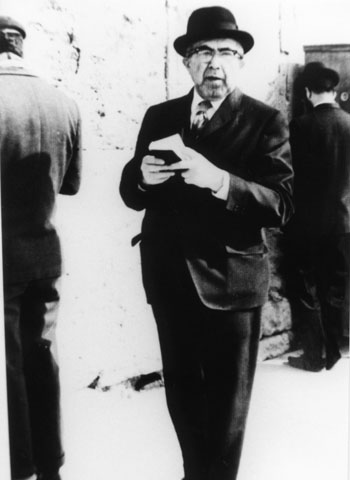

Samuel and Nesha Korff by the Western Wall in Jerusalem during their last trip to Israel

Samuel Korff with prayer book in hand at the Western Wall

A GREAT LEADER IS LOST

Samuel Korff did not live long enough to celebrate the Bar Mitzvah of his grandson Michael.

On December 18, 1974, Samuel Korff died at Massachusetts General Hospital. An honor guard of Boston firefighters escorted the funeral cortege. Rabbi Albert S. Axelrad, the chaplain and advisor to the B’nai B’rith Hillel Foundation at Brandeis University wrote a tribute The Jewish Advocate.

“When Rabbi Samuel Korff died in December 1974, the Jewish community of Boston and beyond sustained a profound loss. I offer this not as a personal testimonial, for during the decade in which our paths crossed professionally, he and I never came to know each other well, but rather from an ideological and communal point of view. During these ten years I have grown to admire his very refreshing orientation to Judaism and the Jewish people, and to respect the progressive and courageous leadership he provided. Rabbi Korff was a rarity in my eyes–one we can ill afford to lose.

“What were his distinctions?

“To begin with, he was an Orthodox rabbi, with a characteristically and predictably strong commitment to Orthodoxy and halacha (Jewish law). At the same time, however, he was a tolerant, open-minded pluralist, devoted to the concept of k’lal Yisrael (the community of all Israel). His Orthodoxy never led him into the dark alleys of pettiness and bigotry, of self-righteousness and rigidity. He avoided the pitfall of offensive military zeal toward his fellow Jews. For example, I cannot imagine him applying the label Ba’al teshuvah (penitent sinner) with its obnoxious implication to any Reform or otherwise positively identified Jew who later turned to Orthodoxy. Rather, while maintaining his own personal and rabbinic commitment to Orthodoxy, Korff consistently gave evidence of accepting and respecting all positive approaches to Orthodoxy–Reform, Conservatism, Reconstructionism, etc. This much is integral to the basic theory behind the organization Korff directed, the Associated Synagogues of Massachusetts, and in his approach to the problem of Jewish religious conflict. Such solid commitment to Orthodoxy, coupled with openness and tolerance, represents to me a breath of fresh air, a quality of traditional Jewish leadership worthy of esteem and emulation.

Reprinted courtesy of The Jewish Advocate.

“Korff was distinguished in yet another way. He insisted in applying Judaism’s ethical, social, and legal tradition to the very real and difficult problems of contemporary society. He was never one to shrink from confronting real problems, thus exerting a positive impact on sensitive, socially and morally concerned traditional Jews, He represented the best in Orthodoxy–a serious concern with ritual and observance on the one hand, and a commitment to making connections between Jewish law and societal issues on the other–both of which are vital elements inherent in Jewish law and learning. Never was he party to the spurious bifurcation between ritual and morality. For Jews who gravitate toward both Jewish observance and social involvement, the Korff model was singularly relevant and inspiring….

“[Korff’s] involvement in the affairs of man was always progressive and compassionate, humanistic and life-affirming. Never would he abandon our tradition’s very central justice-oriented, peace-pursuing and people-loving precepts in favor of illusory self-serving values like narrowly and ephemerally defined notions of Jewish self-interest. The singular direction and landmark decisions of the Boston Bet Din under Korff’s leadership in such verdicts as the condemnation of slum leadership and the affirmation of conscientious objection are tributes to the breadth of his Jewish vision…

“I always admired the tenacity and resourcefulness with which Korff struggled for support and for a place on the map for his undernourished and undersupported agency, the Associated Synagogue…[and] I appreciated the honesty and depth of Korff’s interest in Hillel, in Jews and Jewish life on campus. He did not pay lip service to our cause and constituency but showed real concern, manifest in his consistently coming to our aid despite his very meager funds, his always sympathetic and supportive shoulder, his limitless availability as a Jewish resource and his largely unknown tendency to meet privately and regularly for Jewish study with small clusters of interested Jewish students. Like his other concerns, Korff’s commitment to the campus and its Jews was genuine and refreshing. He and I together always lamented the fact that he didn’t find himself in a position of real influence vis-à-vis the allocation of Boston Jewry’s considerable communal funds. How refreshingly different and correct our communal priorities would have been.

“What a monument it would be to Samuel Korff if there were to emerge from Boston a corps of Jewish leaders dedicated to observing, developing, and applying the traditions of Judaism, representing Jewish religious tolerance, open- mindedness and pluralism, upholding an up-dated appreciation of the classical concept, Elu v’elu divrei Elokim Chayyim (that the variety of positive approaches to Judaism are all the words of the Living G-d)–an accepting, loving view and vision of the whole household of Israel–and committed to progressive social change in line with Judaism’s ideals.”[19]

Twenty years after the death of Samuel Korff, the loss of this great man is still lamented by his family and by the Jewish Community of New England. Rabbi Harold S. Kushner, a Conservative rabbi and the noted author of When Bad Things Happen to Good People, and other best-selling books, explained why:

“When I moved to Boston from Long Island in the summer of 1966 to become rabbi of Temple Israel in Natick, I began to hear of Rabbi Korff in terms of his position with the Vaad HaKashrut, the Bet Din, and the Associated Synagogues. Coming from New York, I had a certain suspicion of Orthodox rabbis and their tendencies to be standoffish and patronizing toward their non-Orthodox colleagues.

“But Rabbi Korff’s reputation was different. I was impressed by his success in centralizing kashrut under the Vaad. In Long Island, kashrut supervisors were employed by the kosher caterers they were supposed to be supervising, and were not taken seriously. I was even more impressed by the Bet Din and Rabbi Korff’s willingness to speak out on social issues usually not confronted by Orthodox courts.

“My real contact with Sam Korff came in 1971-73, when I was president of the New England Region of the Rabbinical Assembly, the organization of Conservative rabbis. Rabbi Korff contacted me with a plan he had thought up to centralize conversion procedures in New England. With typical boldness, he floated the idea of having potential converts appear before a panel of five rabbis, three of them Orthodox or perhaps two Orthodox and three liberal, with one of the liberal rabbis being a graduate of an Orthodox institution. If the potential convert satisfied this tribunal of five, a traditional immersion would follow and the rabbis would all sign the convert’s documents. The three Orthodox musmachim would make the document acceptable in Israel and in Orthodox circles. I was very excited by this prospect and began to discuss it with colleagues.

“Unfortunately, before anything could come of it, Rabbi Korff took ill and had to leave his position. He died shortly afterward. Twenty years later, I feel the community would still benefit from someone of his vision and stature in a position of authority, as it did for many years.”[20]

In 1974, Samuel Korff died at the age of 62. Nesha took it hard, and eventually left Boston.

“My husband was a very energetic person. Three times we were in Israel. Each time I didn’t feel like going because I am not a good traveler. When he came home the last time, he took sick. After he died, I was afraid to sleep alone in the house. Later, I moved to Brooklyn.”

SAMUEL KORFF’S LEGACY

Although neither of the rabbi’s sons chose to enter the rabbinate, others in family carried on the religious tradition. Joseph Korff explained:

“My Uncle Nachum encouraged my cousin Ira Korff to become a rabbi and get a variety of degrees. My father took Ira under his wing, and Ira looked up to my father very much. When my father died, Ira became the next Jewish chaplain of the Boston Fire Department and chaplain of the Deer Island Correction facility.”

Samuel’s sons, though not rabbis, each made a distinguished mark on society. David Korff became a physicist and Joseph an attorney.

In 1960, David married Harriet Shuman, at the time a chemist, and later a financial advisor. They made their home in a variety of places as David’s career went back forth between the private and public sector–Maryland, California, Peabody, Massachusetts and finally they settled in Lexington, Massachusetts. They had four children.

Harriet and David Korff

David Korff died suddenly on August 30, 1988 at age 52. He had been a professor of computer science and professor of physics at the University of Lowell, and had achieved worldwide recognition for his contributions to the field of atmospheric light propagation. During the last years of his life, David was the president of North East Research Associates Inc., a group of scientists and computer scientists who analyzed problems in atomic physics, laser physics, nonlinear optics, and atmospheric propagation.

Joseph Korff, the younger son of Samuel and Nesha, is an attorney in New York City. He and his wife Phyllis have a son and daughter.