A TRUE TALE OF RAGS TO RICHES

According to family tradition, Shloime Goos, the oldest child of Pesach and Chana Goos, left his home in the Ukrainian town of Turiysk in 1898 and immigrated to America. A mere 15 years of age, Shloime arrived at the Port of Boston, alone and destitute. He could not even afford the two-cent fare from the port to East Boston, so he walked. He soon settled in Chelsea, Massachusetts, and Americanized his name, calling himself Samuel (Sam) Gass.

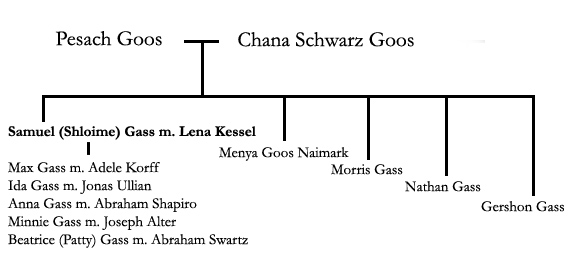

The young man in this photograph is probably Samuel Gass.

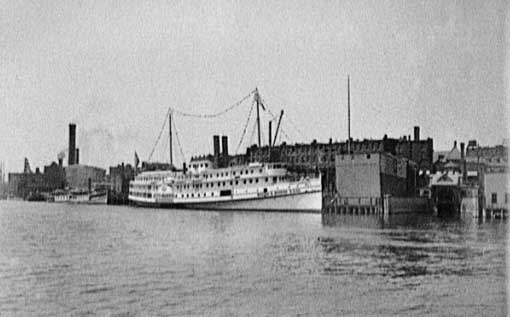

The passenger list for the ship that Shloime sailed on reveals a different story.[1] It shows that Shloime sailed from Hamburg Germany, aboard the S.S. Batavia on May 25, 1903, and landed 14 days later on Ellis Island in New York Harbor.”[2] [3] According to the ship’s manifest, Shloime was 22 years old at the time of his arrival. (It is not clear that this was his true age as the year of his birth was never firmly established and Sam Gass gave different birth years on different documents.)

When Samuel Gass left his home in Ukraine, did he depart from this railroad station in Turiysk or did he walk? (Many emigrants were too poor to afford train fare so they walked to the nearest seaport, often traversing hundreds of miles.)

![These colorized photographs were created between 1890 and 1900 and show the docks and warehouses in Hamburg, Germany, as Samuel Gass probably saw them. Credit: Detroit Publishing Company; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsca, no. 00426 and LC-DIG-ppmsca, no. 0427]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/twohamburg00426uw.jpg)

These colorized photographs were created between 1890 and 1900 and show the docks and warehouses in Hamburg, Germany, as Samuel Gass probably saw them.

Credit: Detroit Publishing Company; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsca, no. 00426 and LC-DIG-ppmsca, no. 0427]

![Wood engraving of German emigrants in Hamburg boarding a steamer bound for New York, 1874. The conditions were not much different when Samuel Gass sailed from the same port 29 years later. Credit: Illustration in Harper’s Weekly, 7 Nov 1874; pp. 916-917. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: LC-USZ62-100310].](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/emigrants3c00310uw.jpg)

Wood engraving of German emigrants in Hamburg boarding a steamer bound for New York, 1874. The conditions were not much different when Samuel Gass sailed from the same port 29 years later.

Credit: Illustration in Harper’s Weekly, 7 Nov 1874; pp. 916-917. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: LC-USZ62-100310].

![When Samuel Gass sailed out of Hamburg’s harbor in 1903, he probably saw masted ships similar to these. Credit: Detroit Publishing Company; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsca, no. 00420]. Created between 1890 and 1900.](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/ships00420uw.jpg)

When Samuel Gass sailed out of Hamburg’s harbor in 1903, he probably saw masted ships similar to these.

Credit: Detroit Publishing Company; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsca, no. 00420]. Created between 1890 and 1900.

![Samuel Gass's voyage on the S.S. Batavia broke the record at that time for the greatest number of people carried into the port of New York on a single vessel at one time. There were 2,584 passengers crowded aboard the ship, which docked on June 8, 1903. This vessel is not the Batavia. (It is the S.S. Patricia, photographed on December 10, 1906) but the image gives an idea of how densely packed the steerage deck of Sam’s ship must have been, and the Batavia’s manifest shows that Sam traveled in steerage.[1] Credit: ©1906 Edwin Levick. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-11202]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ellis-Island-passengers-on-ship3a13598uw.jpg)

Samuel Gass’s voyage on the S.S. Batavia broke the record at that time for the greatest number of people carried into the port of New York on a single vessel at one time. There were 2,584 passengers crowded aboard the ship, which docked on June 8, 1903. This vessel is not the Batavia. (It is the S.S. Patricia, photographed on December 10, 1906) but the image gives an idea of how densely packed the steerage deck of Sam’s ship must have been, and the Batavia’s manifest shows that Sam traveled in steerage.[1]

Credit: ©1906 Edwin Levick. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-11202]

![The Statue of Liberty was the first structure on American land that immigrants saw when their ship approached New York Harbor. It served as a beacon of hope. Credit: Left: Wood engraving published in Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper July 2, 1887, pp. 324-325. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZC2-1255]; right: ©1894 J.S. Johnston, N.Y. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-40098].](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Statue-of-liberty-and-ship3c13735ufixedw.jpg)

The Statue of Liberty was the first structure on American land that immigrants saw when their ship approached New York Harbor. It served as a beacon of hope.

Credit: Left: Wood engraving published in Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper July 2, 1887, pp. 324-325. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZC2-1255]; right: ©1894 J.S. Johnston, N.Y. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-40098].

On June 8, 1903, the skies over New York were stormy.[2] So Samuel Gass probably did not get a clear view of the Statue of Liberty, and when he stepped ashore on Ellis Island he probably did so in the rain.

![Ellis Island Credit: ©1905 A. Loeffler. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-37784].](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ellis-Island-3a38144uw.jpg)

Ellis Island

Credit: ©1905 A. Loeffler. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-37784].

U.S. government inspectors boarded the ship and screened the immigrants for contagious diseases, such as smallpox, scarlet fever, and measles. Those who failed this screening were either sent to a hospital for treatment or targeted for an intensive medical exam after disembarking at Ellis Island.

![Government inspectors boarded ships from foreign ports to identify passengers with infectious diseases. Credit: ©1902 William H. Rau. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-7307].](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ellis-Island-immigrants-coming-to-America3a09957uw.jpg)

Government inspectors boarded ships from foreign ports to identify passengers with infectious diseases.

Credit: ©1902 William H. Rau. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-7307].

![Barges transported immigrants from their steamship company’s dock to Ellis Island. Immigrants then walked from the barges to the main building on Ellis Island. In the background is a hospital where ill passengers were dispatched. Credit: Created 1902 Unidentified photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-12595].](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ellis-Island-landing-there3a14957uw.jpg)

Barges transported immigrants from their steamship company’s dock to Ellis Island. Immigrants then walked from the barges to the main building on Ellis Island. In the background is a hospital where ill passengers were dispatched.

Credit: Created 1902 Unidentified photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-12595].

![This great hall in the main building on Ellis Island was called the registry room. Here, the grueling processing procedure to gain admission to the United States began in earnest. Credit: © 1904 Underwood & Underwood. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-15539].](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ellis-Island-registry-rooml3a17784uw.jpg)

This great hall in the main building on Ellis Island was called the registry room. Here, the grueling processing procedure to gain admission to the United States began in earnest.

Credit: © 1904 Underwood & Underwood. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-15539].

![The dreaded eye exam Credit: Left: ©1913 Underwood & Underwood. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-7386]; right: ©1911 Unidentified photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-40103].](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ellis-Island-eye-exam3a10036uw.jpg)

The dreaded eye exam

Credit: Left: ©1913 Underwood & Underwood. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-7386]; right: ©1911 Unidentified photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-40103].

![Additional buildings used by the U.S. government to quarantine immigrants with contagious diseases. Credit: Created 1902 Unidentified photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-116221].](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ellis-Island-complex3c16221uw.jpg)

Additional buildings used by the U.S. government to quarantine immigrants with contagious diseases.

Credit: Created 1902 Unidentified photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-116221].

![People who passed the inspection process at Ellis Island were discharged here and were free to start their lives in America. Credit: Created 1902 Unidentified photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-93251].](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ellis-Island-final-discharge-3b39451uw.jpg)

People who passed the inspection process at Ellis Island were discharged here and were free to start their lives in America.

Credit: Created 1902 Unidentified photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-93251].

Shloime apparently traveled to America with a 36-year-old man from Turiysk,[3] Leiser Reich (later known as Louis Rich). Shloime and Leiser’s names appear on the same passenger arrival manifest and Hamburg emigration list, and both men indicated on the passenger manifest that they planned to join Samuel Gass at 184 Hancock Street in Bangor, Maine. Shloime identified Samuel Gass as his father, and Leiser described him as his brother-in-law.

But we know from family tradition that Shloime’s father, Pesach, never left the old country. What isn’t known is what Shloime’s true relationship was to this Samuel Gass in Maine. Was he a blood relative or just a landsmen (a person from the same place in the old country)? What also isn’t known is the relationship of Leiser Reich to Shloime and Samuel Gass.

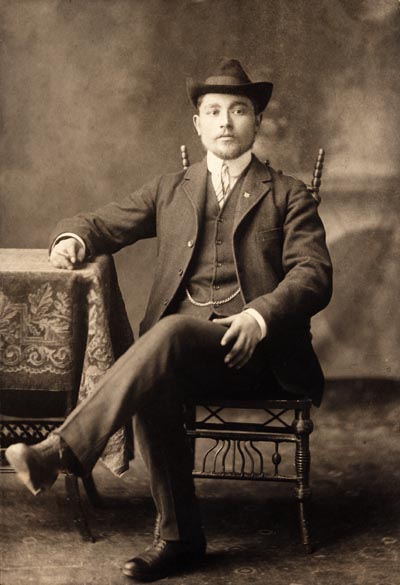

A steamboat owned by the Boston Bangor Steamship Company docked at the waterfront in Bangor, Maine, 1902. Could Samuel Gass have traveled on this steamship when he came to Bangor for the first time? Did he take it when he left Maine for Chelsea, Massachusetts?Credit: ©1902 Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-11202].

Haymarket Square, Bangor, Maine in the early 1900s. Shloime likely became familiar with this area when he went to Bangor.

Credit: © circa 1904 The Metropolitan News Co., Boston, Mass. and Germany

It is probable that Shloime traveled to Bangor, Maine, with Leiser Reich. At some point, (we don’t know how soon after) Shloime decided to settle in Chelsea, Massachusetts. His motivation for moving from Bangor is also unknown. Did Sam join landsmen or did he simply decide that Chelsea was a better place to seek his fortune?

What kind of world did Samuel enter as a new arrival?

Read about Chelsea, a city of opportunity.

The Rag Business

IN CHELSEA, SAMUEL GASS, the greenhorn from Turiysk, found a haven for Jewish immigrants and a place where his Yiddish was readily understood. Although virtually penniless, Samuel possessed a keen business sense. He worked hard, saved his money, and within a few years of arrival he was able to enter the rag business with Isaac Razin, another Russian immigrant living in Chelsea. Isaac’s son, Hyman Razin, explained how the partners got started and why they decided to go into the rag business:

“The two men were friends—both had intelligent minds and liked and respected each other. Once Isaac had been in a shop where he observed how hard and well Samuel worked and knew he would make a good business partner. But why the rag business? In the early 1900s, shmattes, [rags] was a big business in Chelsea and a virtual Jewish monopoly. Though neither had much experience in the rag business they chose their vocation because, as Orthodox Jews, they observed the prohibition against working on the Sabbath—Friday sundown to Saturday sundown. Samuel and Isaac knew none of their Jewish competitors would violate the Sabbath. They all shut down at 3:00 on Friday afternoon and didn’t reopen until the following Monday morning. Samuel and Isaac could safely shut down their business on Saturday and not lose customers.”[4]

Hyman Razin

Hyman described the way the rag business worked.

“It began with rag peddlers who rode through the city on horse-drawn wagons yelling, RAGS and buying rags, used clothing, scrap metal and other items that they resold to firms like Gass and Razin. About five or six rag collectors worked the streets of Chelsea. Each had his own route and people knew what day and time to expect them to appear. Samuel and Isaac also purchased rags from larger collectors and junkyards…

“The rags were sorted and graded by quality, color, texture, fiber content, and had to be separated from foreign materials. Sometimes the rags smelled and insects and rodents were a nuisance. After the rags were categorized, they were bailed using a baling press, and held together with burlap and wire. The bales were then sold to dealers, mills, exporters, importers, agents for manufacturers, other middlemen, and the government.Rag collectors in New York City, circa 1896

Credit: Photographer: Elizabeth Alice Austen; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-76959Rag workers sorting and grading rags. Shapiro Company, Baltimore, Maryland, 1942

Credit: Photographer: Howard Liberman; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USE6-D-002244 and LC-USE6-D-002245]“The price was determined by supply and demand. The Daily Mill Stock Reporter, published in New York, quoted daily prices for rags much like the Wall Street Journal quotes daily stock prices today. Eventually, the rags ended up in the possession of reprocessors and manufacturers who washed and chemically cleaned the rags before reusing their fiber content. Among the many uses for recycled rag fiber were blankets, army and navy goods, clothing, upholstered furniture, and automobile upholstery…”Under the name of Razin and Gass, the business did well and the partners prospered. Isaac Razin served as the outside man—he was the buyer and seller. Samuel Gass was the inside man—he was a worker and supervisor in the shop…Bales of rags. Shapiro Company, Baltimore, Maryland, 1942

Credit: Photographer: Howard Liberman; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USE6-D-002243]“Eventually Isaac constructed a modern three-story brick building at the corner of Maple and Summer Streets in Chelsea. He had the expertise to engineer the design and supervise the workers. The building provided approximately 18,000 square feet of interior space. Samuel and Isaac ceased buying from peddlers and brought in rags by the freight-car load from New York, California, and other distant places. They employed five or six workers [mostly Jewish] who could go through a bale of rags (400 to 2000 pounds) a day. Samuel and Isaac stored the rags in their own building and sometimes in a public warehouse when they ran out of room.”[6]A panoramic view of the ruins of the great fire that destroyed much of Chelsea, Massachusetts, on April 12, 1908. It is not clear whether the fire destroyed Samuel and Isaac’s rag business or whether they were even in business together at that time. What is known is that Isaac Razin lost all his possessions in the fire. According to his son Hyman, “My father…experienced the Chelsea flood and Chelsea fire in the years 1908 and 1909. He lost everything in both disasters.”[5]

Credit: ©1908 Geo. H. Walker & Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: PAN US GEOG-Massachusetts no. 16]

Rabbi Baruch Korff, the brother of Samuel’s daughter-in-law Adele, gives some insight into how Samuel’s business dealings gained him respect in the Jewish community:

“There was a synagogue in Chelsea that was called the Shmatafska Synagogue. Shmatafska because all the rag dealers went there. On the High Holidays, the synagogue would sell portions of the Torah reading. The highest bidders would come up and recite a prayer. It was like an auction. And the others watched Shloime. If Shloime outbid his neighbor, they knew business must be good. It was like a barometer. So, Shloime gradually extended his authority in his home to the synagogue. People, particularly among the immigrants, began to call Shloime ‘Reb Shleime,’ an honorary title.” [7]

According to Hyman Razin:

“The rag business was capital intensive and Samuel and Isaac constantly needed funds to buy rags, pay workers, and pay other operating expenses. However, cash flow was impeded because payment on goods sold came 60 to 90 days after the transaction. The business had too many ups and downs, and so in the early 1920s after the economy had soured, Samuel and Isaac mutually agreed to close their business. Both felt terrible but they didn’t want to risk losing the tidy sum they had accrued. They made a wise choice. In 1940, the U.S. government passed legislation requiring the labeling of fiber content in manufactured goods and this was the death knell for the rag business. Consumers did want to buy clothing and upholstered furniture manufactured from rags. Demand for virgin materials and synthetic fibers grew and demand for rags virtually disappeared. But although they dissolved their business, the two men maintained their friendship until Samuel Gass’s death [in 1954]. They both liked the Turkish bath in Chelsea and would meet there often.” [8]

![Ship manifest showing Sam listed as Leb [sic] Guss.](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/pg5003w.jpg)

![Rag workers sorting and grading rags. Shapiro Company, Baltimore, Maryland, 1942 Credit: Photographer: Howard Liberman; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USE6-D-002244 and LC-USE6-D-002245]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/8b01625uw.jpg)

![Bales of rags. Shapiro Company, Baltimore, Maryland, 1942 Credit: Photographer: Howard Liberman; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USE6-D-002243]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/8b01624uw.jpg)

![A panoramic view of the ruins of the great fire that destroyed much of Chelsea, Massachusetts, on April 12, 1908. It is not clear whether the fire destroyed Samuel and Isaac’s rag business or whether they were even in business together at that time. What is known is that Isaac Razin lost all his possessions in the fire. According to his son Hyman, “My father…experienced the Chelsea flood and Chelsea fire in the years 1908 and 1909. He lost everything in both disasters.”[5] Credit: ©1908 Geo. H. Walker & Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: PAN US GEOG-Massachusetts no. 16]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/6a05952uw.jpg)