The Lion Shoe Company

IN 1921, SAMUEL WENT INTO THE SHOE BUSINESS with his three brothers, Morris, Nathan, and Gershon Gass. They established the Lion Shoe Company in Lynn, Massachusetts, then the women’s shoe manufacturing capitol of the United States. Samuel financed this undertaking with most of the money coming from his rag business earnings.[1]

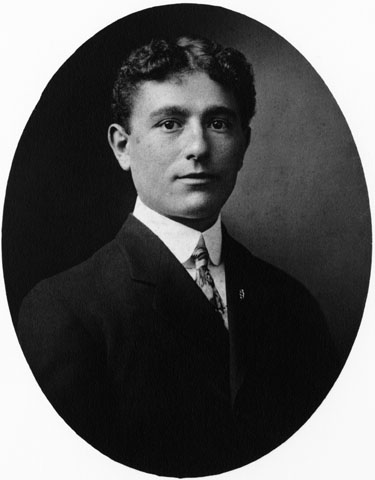

Nathan Gass

According to family tradition, Samuel Gass started Lion Shoe after he and Isaac Razin dissolved their partnership. Yet, according to the Chelsea City directories, Samuel Gass’s occupation is still listed as “Razin and Gass” in January 1921 and January 1922. It appears that Razin and Gass did not dissolve their company until some time after the beginning of 1922, even though Lion Shoe was apparently started in 1921.[2] Although the actual date of the beginning of Lion Shoe and its early business organization are somewhat obscure, it is clear that the brothers ran the company from the start.[3] Sam had invited Isaac Razin to go into the shoe business with them but Isaac refused, fearing that the business would have to be open on the Sabbath.[4]

Read what the Lynn City Directories reveal about the Lion Shoe Company and the Gass brothers.

The original idea for a shoe factory came from Nathan Gass, who was familiar with the manufacturing and merchandising of shoes because as a new immigrant he had worked in a Lynn shoe factory during his first year in America. Nathan wanted to open his own shoe factory, but lacked the necessary capital. For a period of time he lived in San Antonio, Texas, where he was in the fruit business, but Nathan never gave up his dream of operating a shoe factory. Around 1920, Nathan asked Samuel to help him. Samuel agreed and Nathan returned to Lynn. The two siblings invited their other brothers, Morris and Gershon, to join the enterprise and Morris gave up his junk business in Brattleboro, Vermont, to do so.

According to Morris’s son, Sam Gass, the participation of Morris may have been crucial to the business:

“Morris was the kind of person who kept things cohesive. I don’t think Nathan and Samuel would have gotten along that well by themselves. Nothing that I saw was that apparent, but they would pull in different directions. My father would step in instinctively and say whatever had to be said, and it would be done.”

Morris Gass

It is not known what role, if any, Gershon Gass played in Lion Shoe. In October 1923, not long after the company was formed, he took his own life by asphyxiating himself with natural gas from three gas lamps. His death certificate lists his occupation as a laborer and makes no mention of being a shoe worker, which was a familiar designation in the Lynn City Directories.[5] Nobody in the family talked about Gershon after his death. In those days a suicide brought shame to a family and it wasn’t discussed, particularly if there were unmarried children whose matches could be jeopardized. (This prejudice is dramatically shown in the movie Yentl starring Barbara Streisand, based on a story by Isaac B. Singer.)

Sometime after Gershon’s death, Abraham Gootman, Samuel’s brother-in-law, was brought in as another partner. According to family tradition, he was brought in as a replacement for Gershon, yet he wasn’t listed in the 1925 Business Directory as one of the partners.[6]

Abe Gootman

Samuel Gass’s great-granddaughter, Mona Fish, explained how it was possible for a few, poor immigrants to get started in the shoe business:

“Immigrants were able to get into [shoe] manufacturing because only a small initial capital investment was required. Anyone who had $5000 could open a factory. This was made possible, for the most part, by the leasing policy of the United Shoe Machinery Company (USM)…The company monopolized the shoe machinery industry, selling its machines all over the world and servicing the finest shoemakers…USM leased its machines to any would-be manufacturer who seemed to have a reasonable chance of staying in business. Since the chicanery could be leased rather than bought outright, the manufacturer did not need a lot of capital initially. Manufacturers paid USM a minimum monthly charge, plus a royalty on every pair of shoes produced by the machines; dials on the machines recorded the number of pairs produced. USM provided the manufacturers with everything they needed to start a factory. This included not only the machinery, but also shoelaces, eyelets, waxes, tacks and machine parts. Even obtaining floor space was not a major capital investment; it too could be leased. Because a manufacturer’s capital did not have to be invested in machinery or in floor space all of his funds could be directed towards material and labor costs. The immigrant manufacturers were helped here, too, by Jewish leather suppliers who gave them leather on credit.

“Jewish immigrants also formed partnerships to break into the shoe business. Many would not have been able to open a factory alone because they lacked either the necessary capital or shoemaking experience. But partnerships enabled them to overcome these obstacles…Despite the foregoing factors, these immigrants were still entering an industry that had been dominated for years by established firms. While Yankee-owned concerns were leaving Lynn or going out of business altogether during this period, some of the firms continued to operate. These older factories tended to concentrate on women’s high-quality comfort shoes, which sold for ten to twelve dollars per pair retail. The Jewish immigrants did not try to break into this segment of the women’s shoe industry, but chose instead to concentrate on low-priced women’s novelty shoes. The shoes were the extra pair in a woman’s wardrobe; they would go out of style before they would wear out. Because keeping up with style changes was crucial in this line of the business, it involved more risk than the standard shoes, which most of old established firms were producing. But thinking only of the chance for success, it was a risk that the immigrants were willing to take. By not putting themselves in direct competition with the older firms, the immigrant manufacturers encountered less difficulties upon entering the industry…[7]This photograph from 1911 shows the employees of the United Shoe Machinery Co., Beverley, Massachusetts, the company that produced and leased the shoe-making machinery that Lion Gass used.

Credit: @1911 Notman Photo Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: PAN SUBJECT – Groups no. 10]

MONA ALSO EXPLAINED how the Gass brothers ran Lion Shoe.

“The Lion Shoe Company started out as a small firm in 1921, employing only thirty or forty workers and producing around twenty-five cases of shoes per day. After a couple or years, the company decided to expand its business, and moved into larger quarters (four times the size of the first factory). The Shoe and Leather Reporter for 1925 recorded that the company, at its new location, had a $25,000 capital investment and was producing 1800 pairs of shoes daily. The work force grew to 250. The company specialized in women’s novelty footwear, which sold cheaply at less than two dollars per pair. The Lion Shoe Company sold almost half of its shoes outside of Massachusetts: New York, Pennsylvania, Missouri, Ohio, Illinois, Virginia, North Carolina, Texas, California, and Puerto Rico were its markets.

“Lion’s owners took an active part in the factory’s operations. Each partner had a specific function to fill: Nathan Gass was president of the company and took charge of sales; Morris Gass was vice-president and made contacts for the company; Abraham Gootman was treasurer and purchased materials; and Sam Gass was clerk and supervised the operations. The company’s cafeteria was run by a Gass cousin [Louis Gass]. Lion Shoe had a foreman, but the owners ran the business and were in the factory every day. A former Lion shoe worker recalled that Sam Gass continually walked around the factory to see that everyone was hard at work.

“Equal numbers of men and women were employed at Lion Shoe. Most of the women worked as stitchers, while men tended to operate the heavier machines. The shoe workers came from a variety of ethnic backgrounds: Jews, Italians, Greeks, and Poles worked well together in the factory. The workers lived near each other and walked to work together. One former employee maintained that workers did not compete with each other.

These photos were taken of the interior and exterior of an unidentified Lynn shoe factory in 1895 by photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston. The machinery and layout of this shoe factory were probably similar to that used in the Lion Shoe Factory 25 years later.

Credit: Frances Benjamin Johnston; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction numbers LC-USZ62-24327, LC-USZ62-26129, LC-USZ-262-24326, and LC-USZ-262-24310]

“The employees worked long and hard. The workday began at seven in the morning and ended at five or six o’clock. There was a one-hour break for lunch. In the beginning, Lion was open all day Saturday, but later stayed open for only a half day. Workers were paid by the piece, not by the hour. One woman recalled her father totaling his “slips” at home to figure out how many pieces he had finished. In the late twenties a worker’s pay at Lion Shoe was between eight and twelve dollars a week. There was no such thing as an overtime wage. If the shoe worker put in extra hours, he or she was paid the standard piece rate. There were no bonuses or vacations. In fact, people did not even consider taking a vacation. One worker recalled that he got married on Sunday and was back to work at Lion on Monday. Some workers took shoe parts home with them and their families would help out with the stitching. The pay for this extra work was small, but it was welcomed as additional income.”Despite the long hours and low wages, many former Lion workers felt that the Gass brothers were good people to work for. A few employees recalled that the company gave loans to employees. One worker received a $600 loan to buy an automobile. (Of course, the bookkeeper was very careful to take a little out of his paycheck each week to repay the loan.) Lion also ran an annual Christmas Party and a picnic at Canobie Lake Park. The company hired several vans to take everyone to the picnic. One former shoe worker remarked that ‘employers just don’t do things like that any more.’ The company also provided a cafeteria in the factory where the workers could buy and eat their lunches. A daughter of a Lion Shoe worker remembered visiting her father often at the factory. In the summer when all the windows were open, she and her sisters would talk to their father through the open window. Her father would often take them inside and show them the various shoemaking operations. On extremely hot days, the owners would sometimes send everyone home early.

Canobie Lake Park, New Hampshire, in the olden days

“While the Gass brothers did try to maintain this friendly relationship with their employees, their business always came first. The owners had built up their business considerably since its first few years in operation. In 1930, the Lion Shoe Company had $250,000 invested in it, and its 350 employees were producing 3600 pairs of shoes daily. The company’s net sales in 1934 totaled $650,000. The success of the Lion Shoe Company was due to the particular way the owners ran the business. For example, the [competing] shoe factories located in downtown Lynn operated on the basis of a thirty-six pair case. Lion Shoe however, required that there be seventy-two pairs per case. The difference between these two systems became apparent in the wages employees received. For downtown, a worker might be paid one dollar for a particular operation on a case, but at Lion would only be paid $1.40 for a case that was twice the size. The unions tried to force the company to switch to a thirty-six pair case, but never succeeded.

“Another way the Gass owners kept labor costs down was through a contract system they devised. At least four or five departments in the factory were contracted out to individuals. The contract holders hired the workers they needed and paid them with a lump sum from the owners. Their own salary also came from this sum. Fanny Salloway, who held a contract on the packing department, paid the ten women under her according to how fast and how well they worked. But a former shoe worker complained that he was paid less than he deserved under the contract system because his boss kept most of the total payment for himself. The shoe worker recalled that when the contract system was finally abolished in 1929 as a result of the General Strike, he received a much higher payment and his boss quit. The Gass brothers liked this system because they were not directly involved in matters of hiring and wages.

“Although it was generally becoming more difficult for shoe manufacturers to produce for stock because of rapid style changes, the Lion Shoe Company maintained a stock shoe program and was extremely successful at it. While shoe factories were extremely busy when they were producing their Easter and Autumn shoe lines, they went through a three to four month slack period between seasons. During this off- season, many shoe workers were laid off. Lion Shoe’s owners, however, decided to keep their factory open during the off-season to produce a basic walking shoe that was subject to less rapid changes in style. This walking shoe could be produced in large quantities and stored away until an order came in. Buyers knew they could obtain Lion’s inexpensive shoes at any time. In the 1930s, around sixty per cent of Lion’s shoes were made for stock.

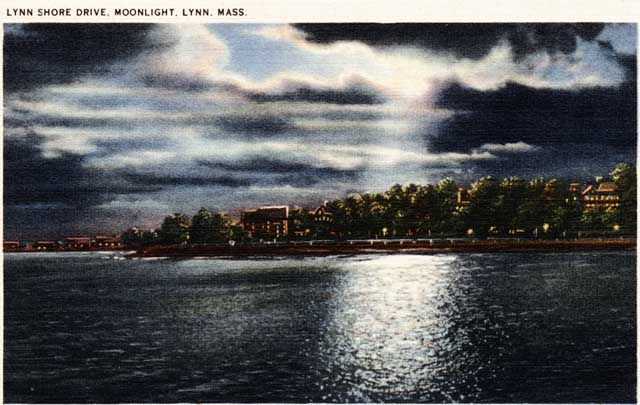

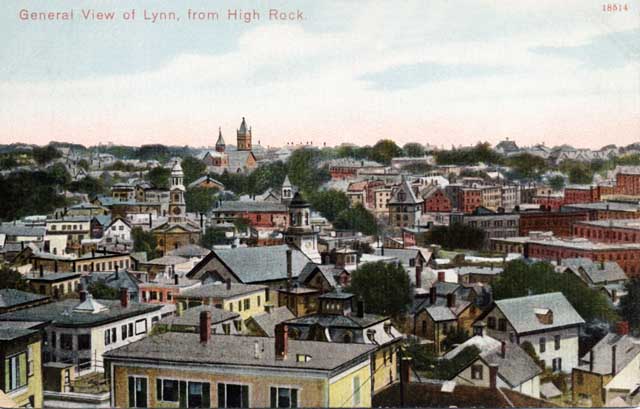

This is what the city of Lynn, Massachusetts, looked like around the time the Lion Shoe Company was in operation and around the turn of the century:

“Not only did this stock shoe program boost the growth and prosperity of the company, it also had a very positive feature for the shoe workers. During this period when there was very little job security to be found, especially once the Depression began, Lion offered its employees stable employment throughout the year. People who were laid off at other shoe factories often worked at Lion until their factories reopened for the next season. Other factories lacked the capital to be able to operate in the off-season

“Although the period that Lion Shoe was in business was a time of strong union activity, its employees were not organized during the 1920s. Lion Shoe’s stock shoe program, which provided job security, may have helped to foster the loyalty of many of its employees. But not all of Lion Shoe’s workers remained so loyal, as a number of them walked out during the General Strike of 1929, demanding higher wages and better working conditions.

“Employees who tried to return to work were harassed by union “goon squads.” The United Shoe Workers of America Union was demanding that Lion buy union-made materials. A shoe worker recalled that Morris Gass tried to point out the unreasonableness of this demand by asking a group of workers how many of them were wearing union-made clothing. It turned out that only Morris was wearing union-made clothing and the employees were left speechless. While other factories gradually reached agreements with their employees, Lion Shoe held out. The owners refused to agree to any wage increase. Lion Shoe workers were desperate and had to live off of funds collected from shoe workers back on the job at other factories. Meetings were held in the Mayor’s office about the deadlocked situation at Lion Shoe, until the Gass brothers finally agreed to a small wage increase and to recognize and negotiate with the United Shoe Workers Union. The contract system was ended. After a five-month lockout Lion Shoe finally reopened as a union shop.

Shoe wholesalers and retailers used trade cards to advertise their newest fashions. No trade cards from the Lion Shoe Company are known to be existence.

“The Lion Shoe Company had another major conflict with organized labor in 1935. The Lynn Joint Council, made up of the locals of each craft, and affiliated with the United Shoe Workers Union, held a contract with Lion Shoe, which was to expire on October 31, 1935. The Joint Council went to Lion Shoe to extend the contract, but the owners refused unless the Council agreed to a fifteen per cent wage reduction. A stalemate resulted. During this period two strikes were called by the Council. The owners of Lion Shoe then made it known through a published statement in the local newspapers that the company was leaving Lynn. A few employees went to the owners and asked them to reconsider their decision. They told the Gass brothers they would form their own union, rather than stay affiliated with United Shoe Workers. These workers held meetings with other employees, agreed to a fifteen per cent reduction in wages and formed the Lynn Shoe Workers’ Union. Lion Shoe’s owners were pleased with these actions and agreed to stay in Lynn. They encouraged their employees to join the new union.

“But in January 1936, the United Shoe Workers Union filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board against the Lion Shoe Company alleging that the Lynn Shoe Workers’ Union was a company union, that Lion Shoe required all employees to join the company union, and that Lion Shoe discriminated against the United Shoe Workers Union. The owners denied the charges and said that the National Relations Labor Act violated the Constitution. The attorney representing the Lion Shoe Company was quoted in the Boston Globe as saying that the firm would take its case to the Supreme Court if necessary. But in May 1937, the National Labor Relations Board declared that the company, having engaged in unfair labor practices, was in violation of the National Labor Relations Act. The Board ordered the company to withdraw its recognition from the company union and to recognize the United Shoe Workers Union as the collective bargaining agency of its employees. The Lion Shoe Company was also ordered to reinstate the striking employees.

“Despite the Lion Shoe Company’s hard line against the unions, it was finding it increasingly difficult to deal with them. The labor trouble, which Lion experienced, seems to have led the owners to consider closing the factory. Another factor which prompted the owners to reevaluate their position was that by the late 1930s, Lion Shoe was operating under an older management team. The owners lacked the vitality that was needed to stay in business and compete with firms in Maine and New Hampshire. Many of their children, having gone to college, were headed towards other occupations, so there was no one to continue the family’s business. The brothers felt too that their children might not do as well in the business as they had done because of the problems plaguing the industry at the time. One son [Samuel’s son Max Gass] decided against going into the business because he felt it would interfere with his practice of Judaism. Although his father was a very pious man and observed the Sabbath, he kept his factory open on Saturdays in order to compete with other firms. He also held Christmas parties for his non-Jewish employees. But he had been willing to make these and other sacrifices to insure his family’s economic security. His son however, who did not have to make these sacrifices, felt that his religion was more important to him than business.

“All of these factors led to the Gass brothers’ decision to close their factory in 1940. In its twenty years in business, Lion Shoe never had a losing year; even during the Depression of the 1930s they made a profit because their shoes were so inexpensive. People bought shoes even during the Depression. When it closed, the firm had amassed enough wealth for all four families to be financially secure.” [9]

The oldest sons of each of the partners had spent time working at the factory and could have kept the business going. Nathan’s son, Harrison Gass, shed more light on the decision to close:

“I’d worked at Lion Shoe for about six or seven months when finally they decided they were going to close the business. Not that they were broke. It was still profitable but it was getting more difficult. The way of making shoes had changed. Instead of stitching the bottoms on, their competitors switched to cementing the soles on. The partners had to change some equipment and they weren’t really up to it. They decided it was time to close the place.

“They weren’t ready to turn the business over to the younger people. They had an agreement that if they ever split up, none of their progeny would ever take over the factory because the others wouldn’t like it. I didn’t understand. Not that I knew much about it, but I knew I could run the business. I knew something, I could have paid them out in time, but they felt they’d all do it together or none of them, so they closed the factory.”

Read more about the shoe business in Massachusetts.

Sam Gass

After the Lion Shoe Company was dissolved, Sam Gass returned to the rag business, helping his son Max set up the Liberty Wool Stock Company in partnership with Max’s cousin Nathan Cutler and brother-in-law Jonas Ullian.[10] The business was located on Second Avenue in Chelsea. Anna and two of the other Gass daughters helped with the business. Postcards and letters written by Sam to the family provide insight to the dynamic between Sam Gass and his now-adult offspring.

Read Samuel Gass in his own words, albeit translated from the Yiddish.

![This photograph from 1911 shows the employees of the United Shoe Machinery Co., Beverley, Massachusetts, the company that produced and leased the shoe-making machinery that Lion Gass used. Credit: @1911 Notman Photo Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number: PAN SUBJECT – Groups no. 10]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/unitedshoe6a25872uw.jpg)

![These photos were taken of the interior and exterior of an unidentified Lynn shoe factory in 1895 by photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston. The machinery and layout of this shoe factory were probably similar to that used in the Lion Shoe Factory 25 years later. Credit: Frances Benjamin Johnston; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction numbers LC-USZ62-24327, LC-USZ62-26129, LC-USZ-262-24326, and LC-USZ-262-24310]](http://paulgassfamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/pg4017w.jpg)