| RABBI BARUCH KORFF |

|

After the creation of the state of Israel, Baruch returned to a more traditional career path, serving as a congregational rabbi.

One of the staunchest and most articulate defenders of President Nixon during the Watergate Scandal, Baruch founded the National Citizens Committee for Fairness to the Presidency in 1973 to generate support for the beleaguered president. A year later, he established the President Nixon Justice Fund, which raised $350,000 to pay for Mr. Nixon's legal expenses. As a result of his efforts on the President’s behalf Baruch became a member of the inner circle of the White House and remained close to Nixon after he left office. Baruch’s close association with Richard Nixon began with the Senate Watergate hearings in 1973, when Baruch was a retired rabbi living on a farm in Rehoboth, Massachusetts. He became convinced that the President was being persecuted by Congress and the press.

“As I watched on television,” said Korff, “my disbelief grew into disgust, then anger. For four-and-a-half months Nixon’s reputation was publicly attacked, and the authority of his presidency weakened, in proceedings that were ostensibly a quest for truth but struck me as nothing more than a clash of political ideologies, an attempt to reverse the 1972 election results. It was a highly one-sided clash as well…

“I have always leaned to the right politically, though I supported the Democratic candidate in four of the thirteen presidential elections I have voted in. In 1960 and 1968, in fact, I voted for Nixon’s opponent.

“But the catalyst for me, having spent more than half my life working to rescue Jews around the world, was that Richard Nixon was the single most powerful ally of that cause. In 1972 alone, at his intervention, Leonid Brezhnev released more than 30,000 Jews, a six-fold increase over the previous rate of exodus. The rate in 1973 was even greater.

“Nixon was also the leader of Israel’s foremost ally. Preserving the influence of his office was important then, and for the future, not least because of the politics of oil in the Middle East.

“These is a classic Jewish concept, derived from the Psalms of David, known as Hakoras Hatov (pronounced Ha-KOH-ras Ha-TOVE), or sense of gratitude. The greater the need for help, the greater the obligation to show gratitude for that help… Which made more troubling to me the fact that so many Jews were in the anti-Nixon camp… But rescuing Jews is a black-and-white issue to me. So I particularly resented the ingratitude of anti-Nixon Jews…

“I was also concerned that the powerful forces of antisemitism latent in the United States, most of whose practitioners sided with Nixon politically, could be aroused by the presence of so many Jews in the liberal coalition against him. A rabbi visible in his defense might help defuse those forces and prevent as well a backlash against our alliance with Israel.

“Did I think Nixon was innocent of the charges against him? Initially yes…”

“Scrupulousness about means is not only justified it is required when there is a safety margin. That is what being civilized means. But I saw no safety margins during Watergate for the issues that mattered to me. Whether Nixon was guilty or not, therefore was of limited importance to me. Not only did I tend to believe him, I thought ends took precedence.

“So after the New York Times rejected a letter I wrote on July 1 defending Nixon, I picked up the phone and persuaded seventeen friends and acquaintances to join with me in trying to turn public opinion around. With $1,000 from me, $2,000 from the friends, and a bank loan, in we plunged. The first ad of the National Citizens Committee for Fairness to the Presidency appeared in the Times on Sunday, July 29, 1973.”[1]

|

|

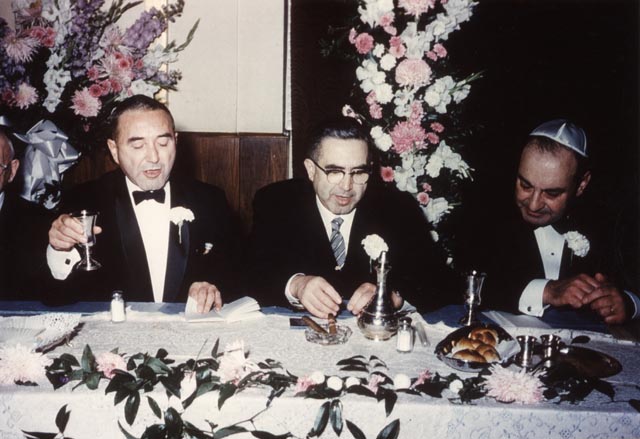

Despite his busy life, Baruch (left) made time for important family events, including this simcha, circa 1973. Here, he is leading the blessing over the wine. Joining him are his brother, Rabbi Samuel I. Korff (center) and brother-in-law, Max Gass. |

Click here to read how Baruch became Nixon’s rabbi.

The former President was obviously moved by Baruch’s friendship, as he mentioned the rabbi in his biography. Here Nixon described Baruch's reaction to his decision to resign from the Presidency:

“Rabbi Korff summoned his usual eloquence and said that although he would accept whatever I decided, he felt obligated to say what he thought. You will be sinning against history if you allow the partisan cabal in Congress and the jackals in the media to force you from office, he said.

“He spoke with the fire of an Old Testament prophet, but he saw that my mind was made up. He said that if I did resign, I owed it to my supporters to do it with my head high and not just slip away." [2]

Baruch described his relationship with Richard Nixon in his own book, The President and I, and even spoke of his memories of the oval office only days before his death in 1995.[3]

Baruch Korff made numerous enemies as a result of his defense of President Nixon, many of whom were quite viscous in their attacks. Some made their displeasure known directly to his face, spitting out their venom even when his young daughter Zamira was by his side. Other critics, those appealing to a wider audience, lambasted him, ridiculed him, and lampooned him in the media.

“Rabbi Alexander M. Schindler, president of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, called Korff ‘an apologist for rampant immortality’ and suggested that many people in the Jewish community were embarrassed by his actions and statements.”[4]

However, one writer, columnist Marc Fisher of the Washington Post produced a well balanced treatment of Baruch’s life, taking into account the opinions of his detractors but capturing the essence of his greatness. It is reprinted here with his permission.[5]

|

|

[1] The President and I,

pp. 3-6.

[2]

Nixon, Richard:

RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon, Grosset & Dunlop, 1978.

[3] Interview

with Rabbi Baruch Korff; 133 Brown Street, Providence, R.I., by Susan

Sekuler, July 1995. Transcript held in 2004 by Paul Gass, Gloucester, MA.

[4]

“Baruch Korff, 81, Rabbi and Defender of Nixon” by Eric Pace, The New

York Times, New York, 27 January 1995.

[5]

“Korff was as loyal as they come” by Marc Fisher, Washington Post,

Washington DC, printed in the Attleboro Sun Times, Attleboro,

Vermont, July 30, 1995.