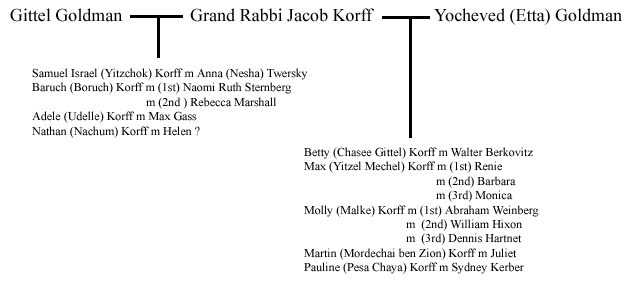

THE ZVILLER REBBE

WHEN GRAND RABBI JACOB ISRAEL KORFF DIED IN 1952 at his home in the Boston neighborhood of Dorchester, more than 5,000 mourners paid their respects, including Boston Mayor John Hynes and Massachusetts Governor Paul A. Dever. Boston had never seen such an outpouring of grief for a Jewish leader. Who was this Rabbi Korff and why was he so revered?

Jacob Israel Korff was born in Medzhibozh, Russia, on 26 Tishri 5643 (October 23, 1883), and became an esteemed leader of the Hasidic movement, first in Russia and later in America. Korff was part of a dynasty of rabbis that stretched back at least eight centuries and included the Ba’al Shem Tov, the Ba’al Shem Tov’s grandson Rabbi Baruch of Medzhibozh, and the Hasidic dynasties of the rebbes[1] of Medzhibozh, Chernobyl, Karlin, and Apte. Yet, Jacob’s ascension to Grand Rabbi of Zvil at the tender age of 24 created quite a stir:

Thousands of mourners filled the streets of Dorchester during Grand Rabbi Korff’s funeral procession.

“In the beginning of the [20th Century] he married Gitla, daughter of the tzaddik Rabbi Michaela [Yechiel Michel Goldman], the oldest son of thetzaddik Rabbi Mordichla of Zvil…After their marriage he settled in Zvil [known today as Novograd Volynsk], was supported for some years at his father-in-law’s table, and blessed his time learning Torah. In the meantime, Rabbi Michaela, relying on his standing in the town and his influence on a known part of the public, was laying the groundwork for his son-in-law to become rabbi of the town.

“This created a controversy among the people, not out of personal opposition to Rabbi Jacob Israel, but because they saw this as an insult to the judges of Zvil.

“After the death of Rabbi Moshe Shmuel [the last chief rabbi of Zvil] his position was to have been filled by his son and heir, Rabbi Yoel Hadin, who was working as a rabbi in Ranovka. He moved to Zvil, but because of his humility he didn’t agree to put the crown of chief rabbi on his head, and consequently none of the other rabbis dared to reach for the crown. [Note: The use of the term crown is metaphorical.]

“Even the oldest of the judges, Rabbi Alter, a judge of noble spirit and pure soul, who certainly was a distinguished rabbi…and for whom the cloak of the rabbinate was appropriate, recoiled from this office. And here appears a young man, who has not yet reached the years of strength (30), who is being made rabbi of such a large and important Jewish community… [Rabbi Korff was only 24 years old at the time.]

“This was an event that brought dissension to the city. [But] It was impossible to start a war against Rabbi Michaela, since his name and family heritage loomed large, and many rabbis and ordinary people depended on him.

“The establishment of Rabbi Jacob Israel Korff as a rabbi in the town became a fact. A young man with energy and initiative, he quickly captured the hearts of the residents and their opposition turned to friendship.” [2]

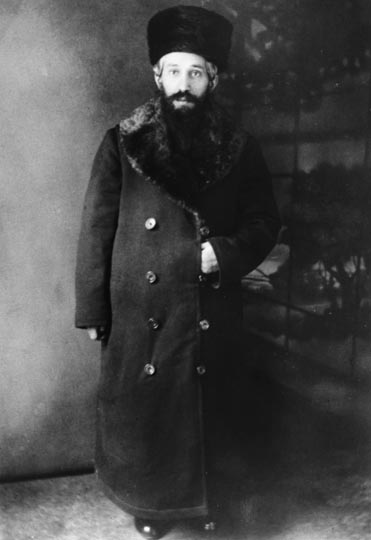

According to his daughter, Adele, “Jacob Korff was a tiny man but his eyes seemed to talk. When people met him, they did not get a sense of power but detected a sense of humility.”

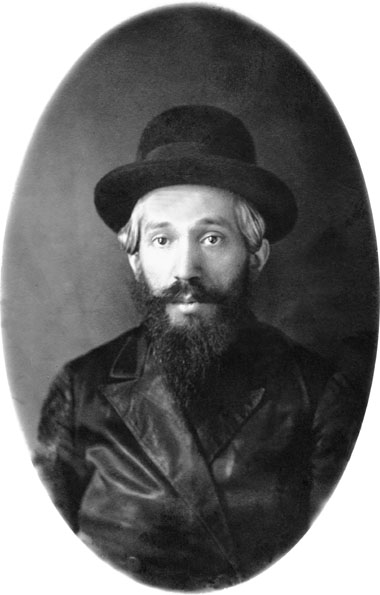

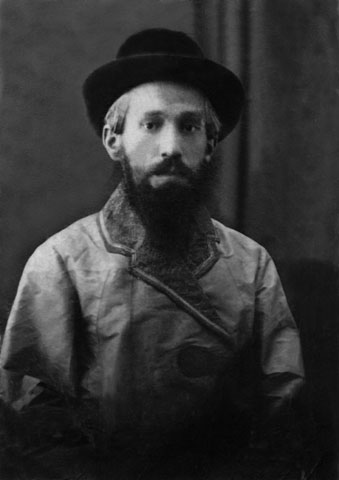

Rabbi Korff in his younger days

Listen to Adele Korff Gass’s talk about her Chasidic heritage:

Zvil or Novograd Volynsk? A word on place names.

RABBI JACOB KORFF’S CAPABILITIES WERE RECOGNIZED at an early age:

“…As a child [Korff] won local fame as an iluy, a child prodigy in the field of rabbinics, and at the age of seven he won commendation when he delivered an intricate Talmudic discourse. When he was eleven years old he was enrolled in a yeshiva and from there he was sent to various rabbinic seminaries in Lithuania.[3] The three years before his ordination were spent at the yeshiva at Navorodok and when he was ordained he received the s’micha [rabbinical ordination] from some of the leading rabbinic personalities of the century. They included Rabbi Yechiel Michal Epstein, compiler of the Aruch Hashulchan,[4] and the well-known saint and sage, Rabbi Mordecai of Oshmino.[5]

“There followed two years of rabbinic research resulting [in] several treatises which won him further signatures for his s’micha from the famous gaon, Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk, Rabbi Shneirson of Kapust, and Rabbi Weil of Kiev.” [6]

The origin of the Korff name

Rabbi Korff was very involved in the betterment of life in Zvil. He worked at bringing order and rule to the existing Jewish institutions and established many new charitable and religious organizations.[7] He also served as the chief justice of the rabbinical courts.

“In this connection, he was noted for his clear-cut decisions, which he wrote himself… His sole objective at all times was to offer justice and to serve the people with all his heart and soul. Many of the rabbinic authorities hailed these decisions as masterpieces in rabbinic lore and impressive in their analytical scheme.[8]

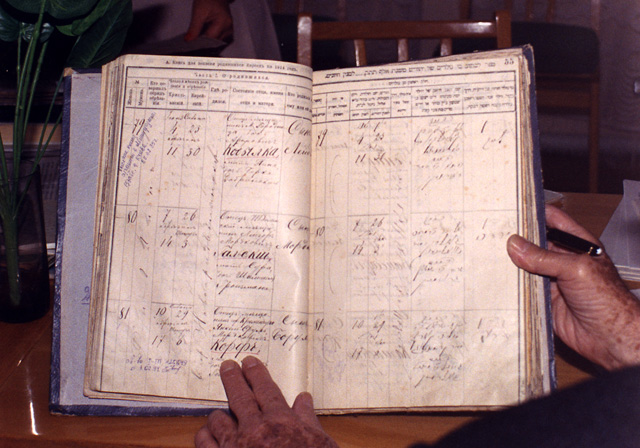

As part of his job as chief rabbi of Zvil, Rabbi Jacob Korff had the responsibility of keeping track of the births, marriages, and deaths of the Jews in the region. His ledgers were stored in the regional capitol, Zhitomir, and can be seen today. This is a close up of some entries from 1917 or 1918 recorded by Rabbi Jacob Korff. The hands in the photograph belong to his son Rabbi Baruch Korff, who visited the archive in 1994.

Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff did not limit his activities to the Jewish community alone. He served in the kisaunya tsud (government) acting as a liaison between the secular authorities and the Jewish community. In the early 1900s Zvil was a city of about 60,000 inhabitants,[9] equally divided between Jews and gentiles. There were three synagogues and four churches. Most of the Christians were Ukrainian Gregorian (Russian Orthodox), although a sprinkling were Roman Catholic.

A street in Zvil (Novograd Volynsk), 1916

Rabbi Korff’s son, Baruch, described the makeup of the town at that time: [10]

“The Jews had prospered in Zvil and on the whole had a much higher standard of living than their gentile neighbors. The Jews were the merchants, landlords, physicians, and lawyers. The Christians for the most part depended on the Jews for their livelihood. They worked as domestics in Jewish homes and supplied the labor for the Jewish-owned sugar refinery. Deep resentment existed among the Gentiles who resented their subservient position. The Jews returned their animosity. Little fraternization took place between the two groups but given the economic circumstances they were compelled to get along.”

The years following the Russian revolution in 1917 were chaotic throughout Russia and the town of Zvil did not escape the turmoil.

“One of the horrible aftereffects of the revolution was a wave of pogroms. The first pogrom began on a Friday at dawn in the old market place. Jewish stands and stores were robbed…Christian peasants from the surrounding area spread terror in throughout the entire day of Shabbat [Saturday]. The Jewish community of Zvil, realizing that they couldn’t standup up against the rampaging peasants, sent a message asking for help from the nearby town of Zhitomir. Advisors from Zhitomir responded immediately, and the first Jewish self-defense group was organized under the leadership of Turkanovski, a student. That evening the self-defense group rode through the town in two trucks shooting into the air. The police who were helping the robbers left and the peasants scattered…It was reported that Rabbi Korff took an active part in the self-defense group. The self-defense group risked their lives trying to help the Jews who were robbed and attacked.”[11]

It may be hard to imagine such a small, pious man standing up to Ukrainian and Russian thugs and armed soldiers and policemen, but Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff exhibited great courage during the anti-Jewish riots that occurred in the wake of the Russian Revolution.

Read more about the anti-Jewish riots in Zvil.

DURING THE HECTIC AND TERROR-RIDDEN YEARS of 1917 to 1920, Rabbi Jacob Korff was not afraid to take even greater risks to bring stability to the town.

“The government of Zvil itself changed hands several times. When the White Russians [the anti-revolutionaries] seized the city and [a] pogrom broke out and many Jews in the community paid the supreme sacrifice, the rabbi took a Torah Scroll and bearing it aloft marched directly to the military headquarters of the conquerors. The commanding officer was startled by Rabbi Korff’s sudden and fearless demonstration.

“To discredit the rabbi and the Jews of the community the officer connived a devilish plan. First, he accused the Jews of harboring the enemy and for that reason many of the Jews had been executed. Second, he challenged the rabbi to go into a local church and pronounce that the accusation was untrue and furthermore that the Jews were not hiding ammunition. Rabbi Korff agreed to accept the officer’s challenge. In the company of a military escort, he marched to the church where he was met at the entrance by the priest. In the courtyard was assembled many of the townspeople. The priest came forth and in no uncertain terms declared that he believed the rabbi and offered a strong plea to the commanding officer to stop killing innocent people.

“Suddenly the commander turned to the rabbi and said, “I’ll believe you only if you will go in the company of my officers to every Jewish home and see to it that every Jew in the community meets at the synagogue and there together take an oath that they did not fight on the enemy side.”

“The rabbi immediately realized that the malevolent plan of the officer was to draw the entire Jewish community to one place– and there slaughter them. The rabbi had no choice but to say that he agreed. The rabbi was furnished with an armed escort and warned that if he returned empty handed he would be shot.

“The rabbi made a pretense that he wanted to stop at his own home first. Here he entertained his escorts with liquid [alcoholic] refreshments–and quietly sent his beadle to warn the people to go into hiding. While all this was going on, the pounding of artillery could be heard [from] across the river, more and more distinctly. As the sounds of the distant guns increased, the more lavish was the rabbi’s entertainment of the officers.

“The pounding of the guns eventually stopped and the news soon spread that the Polish army had marched into the city. The Poles, too, were not cordial to the Jews. They took the rabbi as their hostage and ordered a ransom of 100 horses, 5,000 pounds of flour, a large sum of money, and sundry other items. The rabbi had been held at gunpoint in the town square until the “contributions” were brought in.

“These scenes were repeated countless times during the war and the local government continually changed. Whether it was the White Russians, the Bolsheviks or the Poles, the practice of [killing] the Jews and pillaging their homes was a common occurrence and taxed Rabbi Korff’s leadership qualities to capacity.” [12]

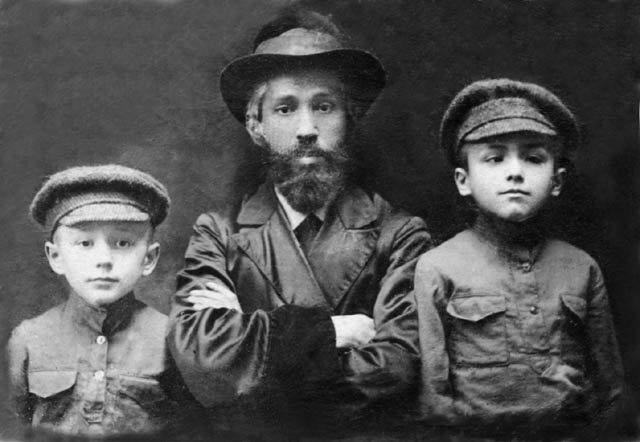

Rabbi Korff with his two oldest sons, Baruch (left) and Samuel

During the worst pogrom in the summer of 1919, the rabbi’s family had its most horrific experience, when Gittel, Jacob’s 29-year-old wife, became trapped during anti-Jewish riot with her four young children.[13] Samuel was then eight; Baruch, five; Adele, two; and Nathan, 11 months. No one knows precisely how Gittel died. There are at least three different accounts of her death. Her son, Baruch, provided his eyewitness account:

“On a weekday afternoon in the late summer of 1919, the bells of all four churches in Zvil began to peal simultaneously. The Gentiles quietly left their jobs and gathered in the streets. The Jews soon followed, and to their horror, they discovered the tolling of the bells was a call to arms. The Christian clergy called upon their parishioners to wreak death and destruction upon the Jews, so the rape and murder began. The Jews fled in terror.

“Gittel clutched infant Nathan in her arms and tried to lead the three other children to safety. A shot rang out and she toppled backward onto pieces of broken furniture, surrounded by the dead and dying. Bleeding from a flesh wound, Gittel nursed her whimpering infant, fearing the cries would endanger all their lives. They remained there, still and quite, Gittel pretending to be dead. Daylight faded into night and the bells finally ceased their ominous call. Scavengers came and combed the area, stripping clothes and valuables from the dead. One approached Gittel and tried to rip her diamond-studded earrings from her ears. She screamed out in pain. The scavenger drew out his gun and pumped her full of bullets. However, the children were spared and they found refuge with Sabina, their Gentile maid. She protected them until it was safe for the children to rejoin their father.”[14]

Another version of the tragedy was described in the press release prepared weeks before Rabbi Korff died:

“As [the Jews] were led to their deaths, the rabbi’s wife called out to the people, Let us walk together. The enemy must not see fear upon our faces. We shall live on! Her heroic expression was halted as a bullet pierced her heart. She dropped to the ground holding in her arms her six-month-old infant, Nathan. Around her were her three other children…The children were soon recognized by one of the hooligans–the Shabbos goy of the rabbi–and the children’s lives were spared.

“While this pogrom was going on, Rabbi Korff was absent from his home…trying to aid in the evacuation of some of the people in another part of the city.[15] A number of the families had lost their homes as a result of a conflagration…caused by the incendiary bombs which had been thrown into the city by the Russians. During this effort, the rabbi was injured and was found lying in the street unconscious by one of the peasants who took him into his home and nursed him for several days.

“After returning to his home and realizing the great tragedy that had befallen so many of the Jewish townspeople as well as himself, Rabbi Korff was determined that the remaining members of the community must find a haven, and he immediately dedicated himself to his plan of having as many of his neighbors as well as his own family migrate to the United States so that they would be safe from degradation and persecution.” [16]

Listen to Adele Korff Gass’s description of her mother’s murder:

(Recorded November 9, 1992 in Winthrop, Massachusetts)

ACCORDING TO RABBI KORFF’S GRANDSON, Joe Korff, Gittel’s children did not like to talk about the pogrom in which their mother was killed. The version he did hear from his father, Rabbi Samuel Korff, who was eight at the time, was somewhat different from Baruch’s memory. Joe recalled:

Rabbi Korff’s wisdom, courage, and leadership qualities earned him the allegiance of thousands of followers. Because of his popularity and many years of service in Zvil, he retained the title, “Der Zviller Rebbe” even after he moved to America.

“I asked my father once how my grandmother had died. I asked who had killed her–the White Russians or the Red Russians [Bolsheviks]. And he said it didn’t really matter, both groups were equally bad to the Jews. But it may have been the White Russians. She was taken up against a wall and shot. He was eight years old at the time, the oldest of his brothers and sister, and he said that Gittel died in his arms.”

Read about Rabbi Jacob Korff’s arrest.

In the end, the exact way that Gittel died was less important than the fact that her family was bereft. Now, Rabbi Jacob Korff had not only the responsibilities of the Jewish community to absorb his time, but he also was the caretaker of four young children. Clearly, he needed a wife to help him fulfill his family obligations.

In June 1921, nearly two years after his wife’s murder, Jacob took his sister-in-law, Yocheved (Etta) Goldman, to be his bride. A year later, Etta gave birth in Korets to a daughter, Chasse (Betty Korff Berkovitz), the first of five children from this marriage.

Learn more about Rabbi Korff’s wives.

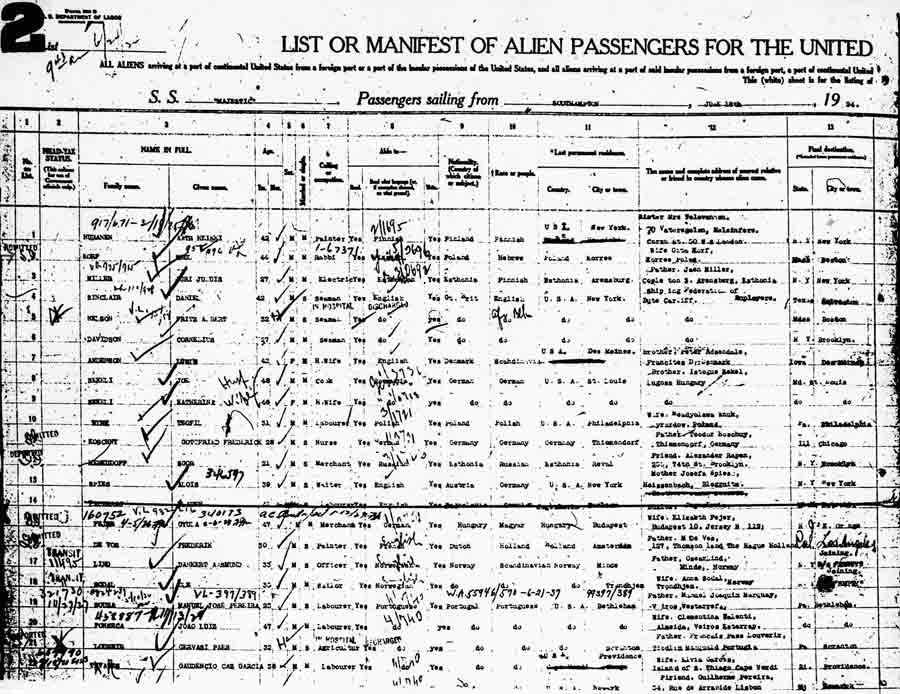

While Rabbi Korff was busy in Zvil helping the Jewish community to weather the effects of World War I, many of his followers had established themselves in America. By 1924, they had saved enough money to pay for the rabbi’s passage. He sailed alone from South Hampton, England, on the S.S. Majestic and arrived in New York on June 18, 1924.[17] His followers settled him in Dorchester, Massachusetts.

This is the S.S. Majestic, the ship that took Rabbi Korff to America. At the time that it was built, the Majestic was the world’s largest ship, weighing 56,621 tons and measuring 956 feet long.

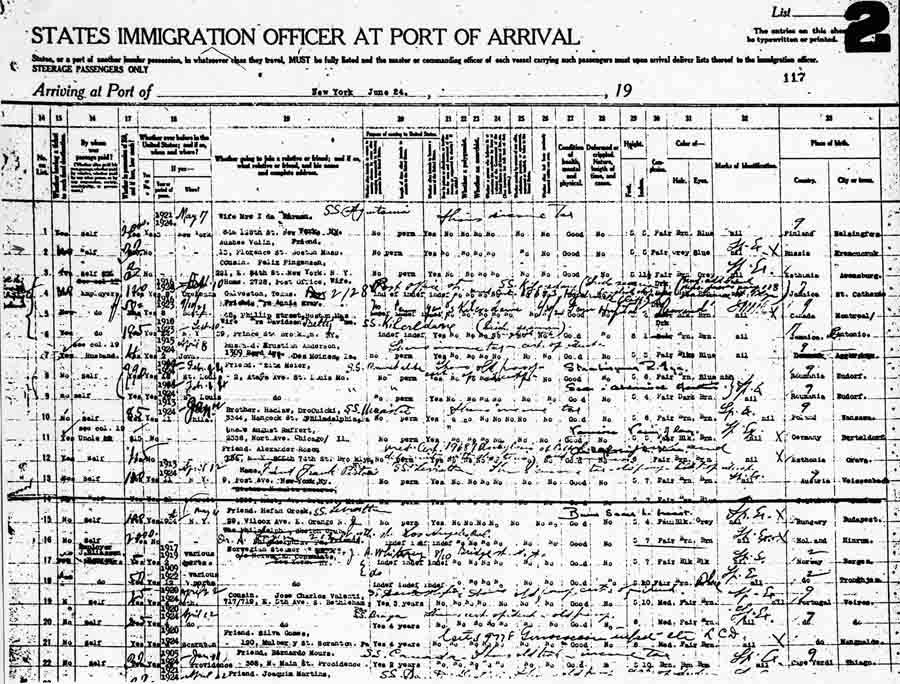

This ship manifest from the S.S. Majestic, which sailed from Southampton, England on June 18, 1924, and arrived in New York six days later, shows Rabbi Korff [spelled Korf] in the second column down. Interestingly, it lists his wife as Gita, an amalgamation of Gittel and Etta. According to this manifest, Rabbi Korff’s birthplace was Kremcucruk, Russia (Kremenchug–SE of Kiev). His wife’s naturalization papers show his birthplace as Padolla, Wolyn, Russia. Neither is correct. Rabbi Korff’s naturalization papers accurately identify his birthplace as Medjubisz, Podolski, Russia. The commonly accepted spelling for the town today is Medzibozh. According to his son Baruch, Rabbi Korff was raised in Medzibozh in the home that belonged to the grandson of the Ba’al Shem Tov

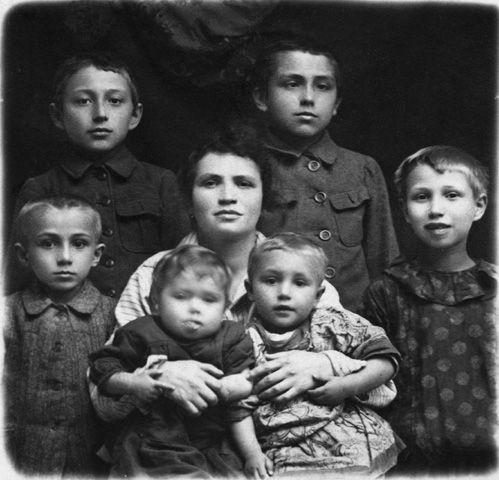

Etta and the children Caption: Etta (center) Samuel Korff (back far-right) and siblings (clockwise) Adele, Nathan, Max, Betty, and Baruch. The children of Gittel never accepted Etta as their new mother, addressing her as “Auntie,” not as “mother.”

Two years later, Grand Rabbi Korff sent some people to Europe to arrange passage for Etta and the six children. The family traveled to America with their own suite of rooms on the S.S. Samaria and their own private kosher dining room. When they arrived in Dorchester they were treated like royalty. The streets were closed and there was a cortege of cars–a real parade. In America, Jacob and Etta had three more children: Molly, born in 1927, Martin, born in 1929, and Pauline, born in 1930.

Rabbi Jacob Korff became a U.S. citizen on November 9, 1931,[18] and his foreign-born children were granted citizenship through him. Etta was naturalized more than 20 years later on December 7, 1953.[19]

The rebbe was not a rich man but he saved up a few thousand dollars and purchased a large house at 163 Woodrow Avenue in Dorchester–to provide a home for his family and a place for people who had nowhere else to go. Although his children often did without, he provided a safety net for the community. Anybody who needed help came to him. Jacob, like all grand rabbis, was a lawyer, teacher, judge, and therapist all rolled into one. And like most rabbis, Rabbi Jacob Korff did not abuse this power; however, he never performed a wedding ceremony unless he knew the participants from childhood, and he never granted divorces.

Listen to Adele Korff Gass’s description of a typical morning in the life of her father grand Rabbi Jakob Korff:

Rabbi Korff’s altruism was part of his heritage. In rabbinical families it was a tradition not to live for one’s self but to help others. The Rebbe’s house was always filled with people–rich and poor alike. They came to hear every word of wisdom that he could offer them. If they needed a meal, he provided it. If they needed clothing, he gave it. The children gave up their beds and cots lined the attic so people without a bed could find shelter for the night.

When people came to Rabbi Korff for advice or legal matters, they left money. He used this money to meet the needs of the poor. His daughter, Adele, once wanted to replace the rebbe’s worn kaputta (long coat) but he refused because he rarely spent money on himself.

Rabbi Korff’s good deeds were listed in the press release distributed during his final illness:

“During all his years of service to G-d and man, Grand Rabbi Korff set up before himself certain personal rules of conduct. First, he never expended a dollar unless he had first set aside ten percent for charitable and religious purposes. This is in keeping with the Biblical tradition of the tithe or ma’aser. Second, his table is free to all in need. Wealthy guests who have come for the rabbi’s advice rub shoulders with unfortunates who sit at the table for a handout. Scholars and laymen, rich and poor are treated alike.[20]

Listen to Adele Korff Gass explanation of her father’s generosity:

(Recorded November 9, 1992 in Winthrop, Massachusetts)

ON OCCASION WHEN THE GRAND RABBI’S OWN FINANCIAL SITUATION was not at best, close friends would advise him to curtail his philanthropic endeavors. To this the rabbi more than once queried, “You’re not asking me to curtail my light and heat and personal food bills, but you say I should cut down on help to other human beings. To help others in need is just as important as to have for one’s self the necessaries [sic] of life.” [21]

After Adele was married and she realized that her father was having a particularly tough year because he had given away all his money, she approached him at the High Holidays, gave him a honey cake, and like his many followers, she asked for his blessing. Like the others, Adele also left some money. This infuriated Jacob. He took the money and sent it to charity immediately, right in front of Adele.[22]

Listen to Adele Korff Gass explain her family’s view of materialism:

(Recorded November 9, 1992 in Winthrop, Massachusetts)

Among the countless incidents told about Grand Rabbi Korff’s magnanimous heart and charitable soul are many that record the part the rebbe played in aiding those who came to Boston as refugees from the Holocaust. One particular occasion was well documented:

“One Friday morning it was noted by members of his family that he was missing from home. He had not left word about going anywhere, and as the hours dragged on, members of the family became quite concerned about his safety. After almost a whole day of anguish, a fleet of taxis suddenly pulled up in front of his home and some thirty-nine foreign-looking men, women, and children emerged from the vehicles. Neighbors and passersby were astounded by this entourage of men with flowing beards, boys with longpe’oth–all typical east European Hasidic Jews, who had been brought by Grand Rabbi Korff to his home directly from the ship as they landed in Boston. None of them had any place to spend the Sabbath and all were reluctant to continue their travels on the Sabbath to their final destinations in New York and Chicago. Food and sleeping quarters were arranged in Grand Rabbi Korff’s home and chapel, and once again he carried out one of his many mitzvot to help his fellow human beings.”[23]

Left to right Baruch Korff, ?, Max Gass (Jacob Korff’s son-in-law), Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff, ?, Samuel Gass (Max’s father), Rabbi Samuel I. Korff

Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff, followed the tradition of the Baal Shem Tov and began his day by daavening (praying) before or around sunrise, He donned two sets of tefillin, Rashi and Rabbenu Tam. He would have first put on his tallis (prayer shawl) and Rashi tefillin, daavened to Ashrei, and then removed the Rashi and put on Rabbenu Tam (except on Rosh Chodesh, where there is a slight difference) and finished daavening. Following tradition, he would have studied after davening, still wearing the Rabbenu Tam tefillin. It is conceivable that he might have removed the Rabbenu Tam tefillin after daavening, eaten breakfast (The rebbe’s typical breakfast consisted of tea, one egg, and a piece of toast) and then donned the tefillin again to study.

Adele Korff Gass described a typical day in her father’s life in America after he finished davening and studying:

“The people would start coming to consult with him. Later, the rabbis would arrive. My father usually met with people in the study. The room looked like a big dining room and contained a table large enough to seat at least 12. There was a couch near the table so my father could lie down when he tired–he had a heart condition. Although the room had curtains, there were no rugs and no decorations on the wall. Books were scattered all over–the couch, on the chairs, on the table. There were no books on secular topics, only Jewish writings. My father also used a small study with a roll top desk and a telephone.

“Intrigued by my father’s constant studying, l once asked, ‘Papa, how much can you learn?’ He replied, ‘The more you learn the less you know.”‘

Shabbos (Sabbath) at the Korffs was a joyous occasion. On Friday evening the candles were lit before going to shul. At the end of services while still in the synagogue, the singing of Sholom Aleichem[24] began and was continued on the way back from shul, and was concluded while walking around the Shabbos table. Then came daavening Minchah and Kabbolas Shabbos. The reciting of kiddush (blessing over wine) and ha-motzi (blessing over bread) came later. The Korffs and their guests would then eat a sumptuous meal. Shabbos hymns, presumably Zmiros, were sung during and throughout the meal

Adele described the scene:

“Sometimes the men danced around the table. Afterward, they discussed the weekly Torah portion and the Talmud. On Saturday after shul, eating again became a focus. The meal consisted of seven things to taste. We would have eggs with onion; liver with onions; onion with herrings, and more. That was the custom. There was always cholent (a slow-cooked stew of meat and vegetables) that had simmered overnight on the stove.

“Each Friday without fail, there was a certain man who came to our house. I would give him some change and his weekend meal–challah, fish, and some canned goods. My father had told us children, ‘if somebody puts a hand out, if you haven’t got a dollar give him fifty cents. If you haven’t got fifty cents, give a quarter. But never, never shame anybody by turning them away.’

The giant challah on the table indicates that this is a special occasion, such as a wedding, not a typical Shabbat dinner. (The use of a camera is another indicator.) Rabbi Korff is the second from the left.)

“One day after the man had finished his meal and left the house, l removed his plate from the table and found two bank books beneath it. On close inspection I discovered that the man had saved a substantial amount of money. I was furious and showed the books to my father. He ordered me to replace the books and the plate, and to pretend I had never seen them. Shortly after, the man returned to the table, clandestinely retrieved his belongings, and departed apparently with the belief that his secret was safe. Under my father’s direction never to shame a person, l continued to serve the man his weekly Shabbos meal but I didn’t load it with extras as I had in the past. Soon after, the man stopped coming.”

Celebrating Betty’s Wedding

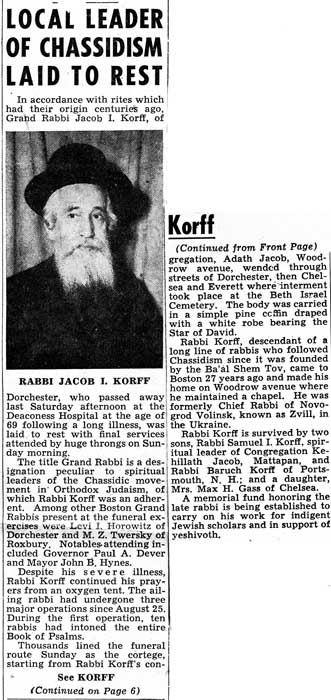

During the last years of his life, Rabbi Jacob Korff suffered from an acute case of spinal arthritis, anemia, diabetes, and cardiac illness. He passed away on Saturday, September 27,1952, in New England Deaconess Hospital at the age of 69, after undergoing three major operations the previous month. Rabbi Korff did not want to die on the Sabbath. He held off death until his son, Rabbi Samuel Korff, completed theHavdaleh service, signifying the end of the Sabbath. He indicated to Samuel with his eyes that his mind was clear and so Samuel recited theVidui, the prayer that is spoken when a person dies. Then the rebbe gave a sigh of relief and expired.

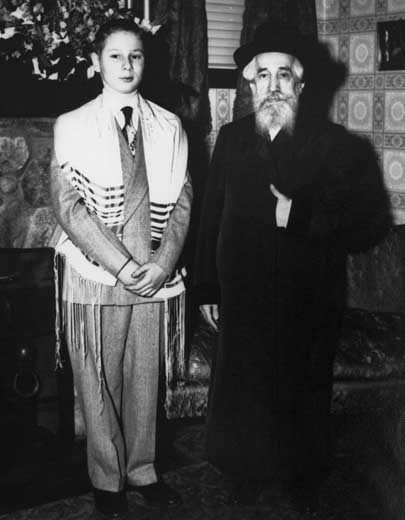

Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff lived long enough to celebrate the Bar Mitzvah of his grandson Paul Gass. Front: left to right: Betty Korff Berkowitz, Adele Korff Gass; second row: Pauline Korff Kerber, Etta Korff, Rabbi Jacob Korff, Paul Gass, Janet Gass; Back: Walter Berkowitz, Max Gass

Bar Mitzvah boy Paul Gass with his grandfather Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff after the ceremony

His body was returned to the chapel in his home on Woodrow Avenue and prepared for burial in a procedure called Tahara (purification). The body was carefully washed from head to toe while appropriate prayers were recited, and then it was wrapped in the white kittel (robe) that the rebbe had worn on Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and Passover. His tallit was draped over the kittel and one of the tzitziot (fringes) was removed as sign that Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff was no longer bound by the commandments of the Torah. Amid numerous candelabra, the rabbi’s body was never left unattended from the time of his death until his burial. This was in accordance with Jewish tradition as a sign of respect.

Approximately 300 rabbis visited the chapel and recited prayers, and selections from the Book of Psalms in a special service of consecration reserved for those who lead a saintly life. This special service began at the time of his death and ended when he was buried the next day. More than 5,000 mourners came to pay their respects but most could not get into the chapel.

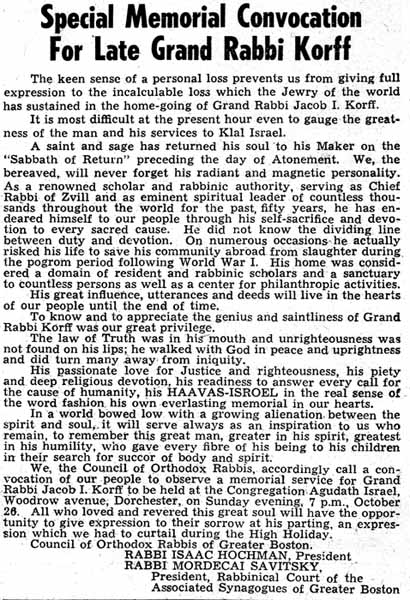

According to his obituary in the Boston Globe: [25]

“Governor Dever and Mayor Hynes headed the official list of mourners, entering the congregation for a last tribute to Rabbi Korff before his body, placed in a pine box fashioned during the night and glued together, was ‘given over to his people’ for a procession through Dorchester and Mattapan streets before being transferred to Everett for burial.

“Thousands lined the streets as the body was borne by relays of the faithful through Woodrow Avenue, Ashton Street, Columbine Street, Blue Hill Avenue to Calendar Street where the casket was placed in a hearse.

Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff’s funeral

“During the procession and ride to the cemetery, stops were made at 12 synagogues while prayers were recited and the psalms intoned on the steps of temples.”

Thousands of people followed the hearse to the burial site at Netzach Israel Cemetery in Everett. Pauline Korff Kerber’s husband Sidney recalls the funeral:

“When Grand Rabbi Korff passed away the family went to the cemetery in two cars. The men all piled into a big black limousine and the women all crammed into my father’s old green Dodge with me in the driver’s seat. I raced through Boston preceded by a police car with sirens blaring and the big black limousine. They could get through all the red lights and across the Mystic River Bridge without stopping for tolls. But every time we came to a red light I had to stop.”

Once all of his family, friends and followers were assembled Rabbi Korff was laid to rest in the family plot at Beth Israel cemetery.

This Ohel[26] was built over the final resting place of Grand Rabbi Jacob Israel Korff, signifying that he was a Tzadddik and Ish Kodosh, a righteous and holy person. It is an ancient custom of Jews to bring their troubles and prayer-requests to the graves of Tzaddikim and Kedoshim(righteous and holy people), especially on the eve of Yom Kippur and on their Yartzheit (anniversary of the death).

The final resting place of Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff

Following his death, Rabbi Korff’s former congregants placed an entry in the Zvil Yizkor Book, which was published in Israel. This moving tribute, which has been liberally quoted throughout this chapter, indicated the love and respect with which Grand Rabbi Korff was remembered by his landsmen.[27]

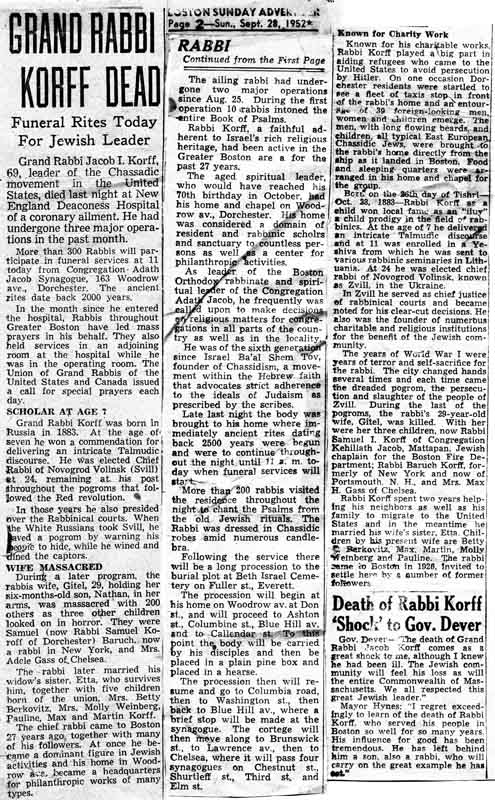

Rabbi Jacob Korff’s death notices

We have made every possible attempt to obtain the necessary permissions to reprint these articles but could

not find the rights holders. Please contact us if you are a copyright holder.