A LIFE TOGETHER

AFTER THEIR HONEYMOON, Max Gass and Adele Korff moved into the home of Max’s parents at 27 County Road in Chelsea, Massachusetts. Adele’s father Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff foresaw conflicts from this living arrangement, which threw two exceptionally strong-willed people together—Adele and her father-in-law, Samuel Gass. According to Adele:

“My father was a very wise man and he said, My child, take a room, but by yourself with your husband. However, my father-in-law wanted Max and me to live in his home. Always a good conniver, Sam said, Even a criminal gets a chance. Try it. If you don’t like it you can move out.”

So the newlyweds joined Sam’s household, which included his wife Lena, their unmarried daughters Anna (age 22), Minnie (age 20), and Patty (age 15), as well as their married daughter Ida (age 25) and her husband Jonas Ullian, a pharmacist. Ida, who had wed nearly 2 years earlier, was pregnant with her first child.

Although Sam was extremely generous and effective in dealing with his extended family and the Jewish community, he had difficulty translating this spirit of generosity to his own immediate family. He ruled with an iron hand and had encountered little resistance from the members of his household until Adele came along. In Adele, he had finally met his match and he respected her feisty spirit. However, his vocal admiration for his daughter-in-law set Adele apart from his daughters and so Adele’s relationship with her sisters-in-law, especially Minnie and Ida, was not harmonious. Adele explained:

“Sam tried to ingratiate himself with me and in the process he fostered animosity between his daughters and me. He praised me, bragging that I could do anything, and if anything needed to be done they should ask me for help. Now, if I was one of his daughters I would have been resentful. He created a lot of hard feelings.”

Adele thought that in addition to her father-in-law’s favor, the gifts she received from Max—a 2½-caret marquis engagement ring and a Persian lamb coat—also made her sisters-in-law jealous, but Adele’s son Paul had a different opinion:

“The tension between my mother and her sisters-in-law probably arose from differences in outlook and lack of maturity. My mother’s personality and background were extremely different from theirs. She was raised in the strict Hasidic tradition of service and sacrifice for the greater good of the community. Her sisters-in-law had experienced a more typical American middle-class upbringing. The friction was more a clash of culture than anything else. In addition, all of them, including my mother, were relatively young when my mother joined the family. They lacked the maturity to deal with their differences.”

The tense living arrangement led Max and Adele to move from 27 Country Road after only a couple of months. Adele explained why Sam fought hard to keep them in his home:

“My father-in- law tried to put obstacles in my way to prevent Max and me from moving out because my husband was the rent collector, the garbage collector, the chauffeur, everything. At that time my husband worked for Sam in the shoe factory and didn’t draw his salary. Sam collected Max’s salary and gave Max an allowance.”

Nevertheless, the couple moved to a spacious, top-floor apartment on Murray Street in Chelsea, and that is where they began their family.

Children

ADELE WAS SO YOUNG and protected when she married she actually was ignorant of the facts of life. One month after her wedding, she became pregnant but didn’t know it. Adele explained how she discovered she was pregnant:

“I didn’t know much about sex and I was so naive that I thought that you got pregnant if you were unwell and got kissed. Max had kissed me when we had a shower and I wasn’t feeling good. I came home, to my father’s house, and I kept punching my stomach. I walked around like death warmed over. And my father said to me, What’s the matter?

“Nothing, I answered. I was so ashamed. I couldn’t be pregnant in his eyes. I was really very ignorant of the facts of life.

I had cramps and my brother Samuel came to visit me. I was in bed and he wanted to know what was wrong. So I told him I hadn’t had my period in more than a month. He called the doctor and the doctor told me I was pregnant and had to stay in bed for a couple of weeks to prevent a miscarriage. My friend, Eva Quacher, came and took care of me. She told me the facts of life.

Paul Gass was born in 1938, the first grandson on both sides of the family. Eight days after his birth, the family had a bris (ritual circumcision), and at that time Paul received his Hebrew name, Pesach, after Sam’s father.[1] A month after Paul’s birth, the family observed another ritual in their home: the redemption, or buying back, of the firstborn son.[2]

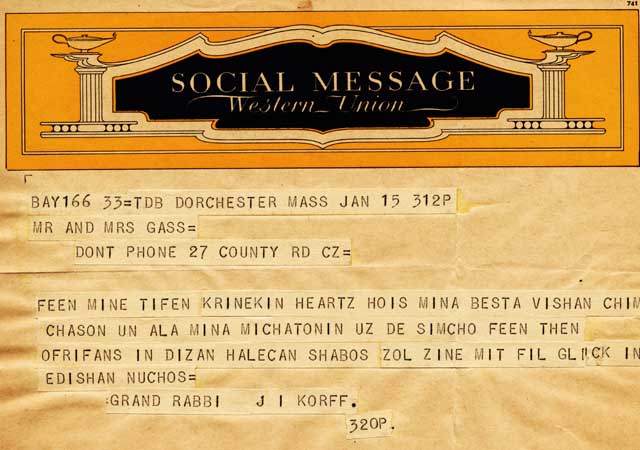

Congratulatory telegram from Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff to Sam and Lena Gass on the birth of their first male grandchild

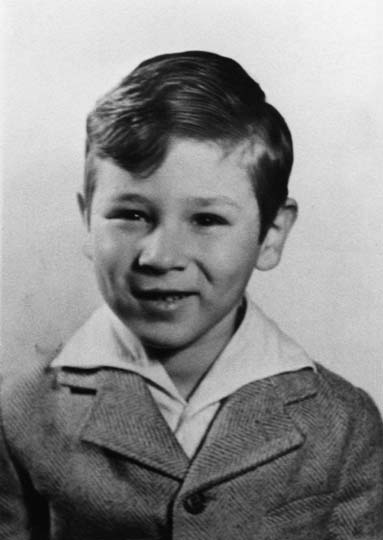

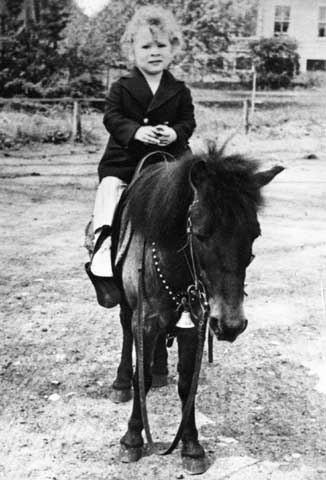

Paul Gass’s early years

Two years later, Adele was pregnant again and the family moved to 33 Fremont Avenue in Chelsea. Adele loved her new surroundings:

“Our Chelsea home was a big house and I loved to garden in the yard. We had a beautiful rose garden with a white trellis through it and around it. I loved to cut the roses and bring them inside. We also grew grapes on another trellis and Max tried to make wine from them in the basement. The grapes would always rot and Max would dump them in the rose garden. We had the reddest wine-colored roses!”

33 Fremont Avenue, Chelsea

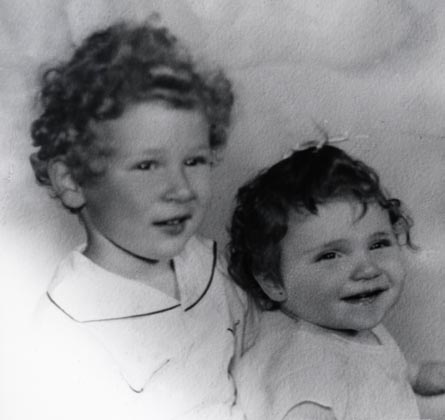

The Gasses second child, Janet was born in the spring of 1940, and the family held a naming ceremony for her at the synagogue, where she was given the name Gittel for Adele’s martyred mother.

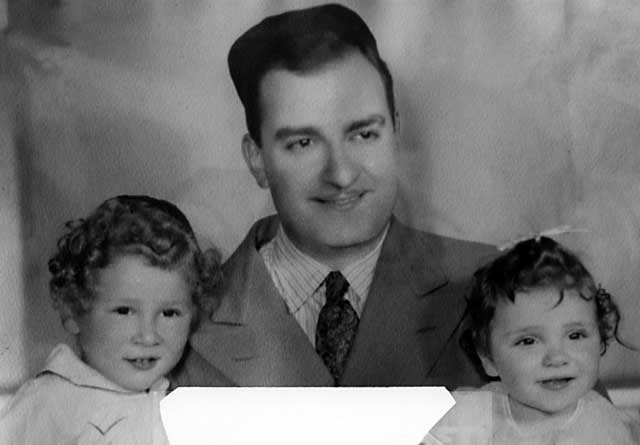

Max, Paul, and Janet

Max and Adele’s third child, Jay Marshall Gass was born in August 1944. At the bris he was given the name Mordechai for Adele’s paternal grandfather.

Read about Adele’s first haircuT.

An Observant Jewish Household

ADELE AND MAX BOTH ADHERED to Jewish tradition. However, Max was more observant and practiced traditional rituals strictly. Adele, more modern in outlook, modified her observances in situations where she found the ritual no longer served its intended purpose. This form of reasoning led Adele to stop going to the mikva (the ritual bath). Adele explained:

“The week before my wedding I had gone to the mikva. According to the Bible, immersion in a mikva is required to restore an impure person to a state of purity. Women are considered to be unclean when they get their periods and they are supposed to abstain from relations with their husbands. On the seventh day after a woman’s period has ended, she is suppose to go to the mikva and then she can resume her wifely obligation.

“After the wedding and up until my father passed away I went to the mikva regularly, and then I didn’t go any more. Going to the mikva was time consuming. I spent about an hour within the mikva building itself and then I spent time traveling back and forth to it. I felt that you could get just as clean in a shower.

“The mikva was like a deep tub. According to Jewish Law, the water in it has to come from a natural source like a well, spring, or lake. Even water from rain or melted snow or ice can be used.

“At the mikva, there is a female attendant who trims your nails. Then you take a bath and clean yourself all over. A covering is draped over you and you walk down a few steps into the mikva. The attendant takes the covering because you are supposed to enter the water without anything on. Next, you dunk once and the attendant says a special immersion blessing. Then you dunk twice more and come out.

“There was a fee. I tipped more because I didn’t want to immerse myself in anybody else’s water. Because the water wasn’t very clean in the Chelsea mikva, I paid the attendant to drain the mikva and scrub the sides before refilling it for me.

“I went to the mikva while my father was alive because when I missed a month meddlers always informed him and I didn’t want to hurt him.”

Portraits of Adele

Daily Prayer and Food Blessings

DAILY OBSERVANCE WAS A GIVEN in the Gass home. Before eating breakfast, Max always said the morning prayers, reciting them at home unless it was a holiday, the Sabbath, or a day that he didn’t go into work. On those days he went to shul [the synagogue]. He began with the Modeh Ani, the first prayer of the day, where he thanked G-d for restoring him to consciousness after his night’s sleep. On weekdays he wore tefillin[1] on the arm and head during the morning service. (Tefillin aren’t worn on Shabbos or on holidays.)

Max practiced ritual hand washing in the morning before he laid his tefillin and davoned (prayed). He filled a special two-handled cup with water and transferred it from his right hand to his left. Then he poured some water on his right hand, transferred the cup back to his right hand, and poured water on his left hand. He repeated these steps twice more and then recited the hand-washing blessing. He also performed this ritual before each meal.

Following Jewish custom, Max always recited a blessing for everything he ate, even snacks. At the beginning of meals where bread was served, he would sprinkle the bread with salt[2] and say the Ha-motzi blessing:

Baruch ata Adonoi Elohenu melech ha-olam, ha-motzi lechem min ha-aretz.

(Praised be Thou, O Lord our God, King of the universe, who brings bread from the earth.)

The Ha-motzi prayer covers all the foods that are eaten during the meal. However if bread is not included then a special blessing for each kind of food is recited. There is a special blessing for vegetables, for fruits, for wine, for beverages other than wine, and a catch-all blessing thanking G-d for creating many types of foods.

Max always bentched (sang grace) after meals. If there were at least three men present—a mezuman (quorum needed)—he began the grace with a special introduction.

Max loved to tell stories, especially ones from the Bible. He would begin with a tale that seemed contemporary in nature but then he would slip in a story from the Bible. He was a master of puns and would try to trick the children into learning about being a Jew.

Janet Gass

Max davoned every night and then he would say the Shema. This was the first blessing he and Adele taught their children and they said it when they were small before going to sleep but as they grew up they stopped saying it at bedtime.

Adele and Max occasionally made time for an evening out during the busy child-rearing years. Top photo: Adele and Max; bottom photo: Adele with her brother Nathan Korff and ??

Shabbos–Sabbath, the Day of Rest

MAX GASS AND HIS FAMILY kept the Sabbath. Adele described what this entailed:

“On Fridays, Max left work early to come home before sundown. Sometimes, he would go to the synagogue. I would light the Sabbath candles and Max would recite Kiddish over the wine and say the Ha-motzi over the challah [braided bread]. Then I’d served the Friday night meal. At the end of the meal Max sang Hebrew songs.

“The candles were lit no later than 18 minutes before sunset. I usually covered my hair with a lace shawl but if I was in a hurry I just threw on a napkin. After I kindled the candles, I moved my hands back and forth over the flames three times, placed my hands over my eyes, and said the blessing:

Baruch ata Adonoi, Elohenu melech ha-olam, asher kideshanu be-mitzvotav, ve-tzivanu le-hadlik ner shel Shabbat.

(Praised be Thou, O Lord our G-d, King of the universe, who has sanctified us by His commandments and commanded us to kindle the Sabbath lights.)

“I kind of meditated after saying the blessing and I blessed my family so they would be well and happy. When I had all three children I lit five candles—one for each family member. And then when I lost Jay, I lit four, than three candles after Janet was gone. Sometimes I would light only two.

“I placed three challahs on the table. Two little ones were used for the Ha-motzi. Over the challah I placed a decorative cover with the word Shabbat embroidered on it in Hebrew. After Max said the Ha-motzi, he removed the cover, broke off a piece of the challah and passed it around. The third challah was normal size and not part of the ceremony, it was just for convenience. It had been pre-sliced and we ate it during the meal. When I was first married I used to bake my own challah. I would let the dough rise overnight and then I would braid and bake it. I even had special pans to make different shapes. Later, I just picked it up at the bakery.

“After the meal I cleared the dishes but I couldn’t wash them and I couldn’t do any more cooking, although I left food on the stove with a low flame burning. Max wouldn’t even allow me to turn on lights. It was like living in my father’s home—come Friday after sundown we weren’t allowed to do anything

“However on the Sabbath, I could prepare food like making a salad, and serving it. I could use knives. The prohibition was against cooking because in the olden days making a fire took a lot of work. You weren’t allowed to do anything that was work. Half of the things that are prohibited in modern times wouldn’t be prohibited if the Bible were written today. The main theme of the Bible was that G-d created the earth and everything else in six days and on the seventh day He rested. When the Bible was written, you didn’t have electric lights, telephones, and cars that started with the turn of a key. Max refused to talk on the telephone on the Sabbath but I did and this bothered him. He didn’t like the idea of my answering the phone and even in an emergency he wouldn’t use it.

“On Saturday mornings Max walked to the synagogue—about three miles away. He walked even in the worst rain and snowstorms because he wouldn’t violate the Sabbath by driving. Max often lead the service in the synagogue. He was like the gabbai, the person who assists in running a congregational service. He’d read and translate the Torah and Haftorah. There were other congregants who could lead the service, too, but Max led the most often. After he died, the Winthrop synagogue placed a plaque in the chapel to honor his memory.

“Sometimes after services Max brought people home for the mid-day meal. If he returned by himself, he would nap after eating. I would be very bored so I just read.

“I never made gefilte fish for Max because he hated it but Paul loved it, so sometimes I prepared it for him. I made mine using pike and white fish—it was very good. I never wrote down the recipe for it or for anything else. I did everything from memory and somehow I managed to make it come out right.

“Max didn’t like tzimmes [a vegetable casserole sometimes prepared with meat] but it was easy to make and it could be reheated without losing its flavor. I made tzimmes with sweet potatoes, carrots, and kishke [a mixture of bread crumbs, spices, and egg stuffed in a casing] and I baked it in the oven. The kids liked it. I only prepared cholent [slow-cooked main dish with meat, beans, and potatoes] for my father-in-law. He used to love stuffed chicken neck with baked beans and potatoes.

“Shalosh Seudos [the third meal] was served before Havdalah. It was a light supper, a milkh [dairy] meal, usually consisting of cheese, lox, tuna, and so on. We never had herring because it came with onions and Max hated onions. However, Max loved kippers. So on Saturdays he got canned kippers but on Sunday when I could cook I made him fresh kippers—they stunk up the house.

“After sunset on Saturday, Max conducted a Havdalah ceremony and then I was free to do anything. Havdalah marks the end of the Sabbath and separates it from drudgery of the work week. We used a special wine cup, and a besomim [spicebox] that I bought in Israel. It contained cinnamon, cloves, and other spices. Max lit the Havdalah candle [a braided candle with two wicks that burned like a torch] and recited a blessing. He would put his fingers in front of the candle and look at his fingernails in the candlelight. We used to say to our children, Hold the candle high so you will grow tall.

“Max blessed the wine and the spicebox and then we passed the spicebox around and sniffed it. He said a few more blessings and extinguished the candle by spilling a little bit of wine on the counter and dousing the candle in it. Then he would dip two fingers in the spilt wine to bring good luck and put his fingers in his pocket.”

Max’s son Paul, did not follow Max’s religious traditions but it did not generate conflict between the two. According to Paul:

“I had a great respect for my father and although I drove on the Sabbath, I always parked the car two or three blocks away from home in a direction I knew he wouldn’t walk in. My mother was aware of this. My father would never acknowledge that I would deliberately violate Jewish laws. After I was married, if he saw something that wasn’t kosher in my house, he would assume that it was something my wife, Judy, brought in by mistake. He rationalized these things. Out of respect for my parents, we always prepared everything 100% kosher for them when they visited.”

Passover

PESACH (PASSOVER)[1], which commemorates the deliverance of the Hebrew people from Egyptian slavery, was a very special time in the Gass household. Adele described Passover in her home:

“Pesach was the most demanding of the Jewish holidays and I used to dread it each year because it was so much work. To commemorate the deliverance of the Hebrew people from Egyptian slavery, the Bible requires that we retell the story of the exodus, remember that once we were slaves in Egypt, and eliminate all hametz [foods that are fermented or can cause fermentation] from the diet and from the home. Wheat, barley, spelt, rye, and oats, and anything made from these grains are hametz except for matzah. In addition the use of utensils—plates, cutlery, pots, pans, etc.—that came into contact with hametz is forbidden unless they are koshered for Passover. This total elimination of hametz serves as a reminder that the fleeing Hebrews lacked the time to allow dough to rise before baking it.

“Max watched over me to make sure I complied with the Biblical commandments. Max didn’t take any short cuts when it came to following Jewish law. Everything in the entire house had to be spotless—rugs, furniture, closets, drawers—everything! I had a separate set of dishes special for Passover that I pulled out each year, but we still needed to kasher [make kosher] other items for Passover. This was usually accomplished by immersing the items in boiling water.

“I removed the shelves from the refrigerator, washed the refrigerator thoroughly, and then I washed it again with baking soda and lined the shelves with aluminum foil. I cleaned the burners of the stove, immersed them in boiling water and then wiped them clean. For the inside of the oven I used Easy Off oven cleaner and then I wash it down with baking soda. It was a lot of work.

“I packed up all my everyday dishes and washed all my cupboards. I had a closed-in porch and I had cabinets built on it. I transferred everything from my inside cabinets to the outside ones. Then I had room for my Passover groceries. After Passover I transferred the outside items back inside.

“For Passover use, I owned two sets of dishes for twelve, plus glasses, utensils, and silverware. These were dishes for flayshig [meat]. We always held big sedars on the first and second nights of Passover with as many as 35 to 60 people, including guests who were not Jewish. We only had a few dishes and cutlery for milchig [dairy] meals for our immediate family to get through the week.

“The night before the first sedar, Max conducted a search called Bedikat Hametz. There was a special blessing before the search began in which we thanked G-d for commanding us to remove the hametz. Max went from room to room with a candle looking for hametz.. I had placed breadcrumbs on the windowsills and he would sweep them off with a feather into a bag. We bundled up the crumbs and the next day we took them to the rabbi. He burned them in an oven and marked down our name.

“My father always wore a kippel [special robe] to the sedar. Sometimes Max wore a kippel, too, but at other times he wore a diner jacket or suit and tie. I made Max a kishn, a special cushion to recline on during the sedar. [Reclining at meals is a symbol of freedom.] We used to have a long Haggadah but I bought a shorter version because the kids got restless. Max didn’t like that. Regardless of how we rushed him, we didn’t get through the sedar until 11:00. He just went on and on and on, especially if he had participants who were interested. I would urge him to read faster, and he would, but he would break to tell stories. Max would have preferred to finish at midnight or later. My father’s sedars lasted until three in the morning.

“I made my own charoset using sweet red wine, Macintosh apples, walnuts, and a little bit on cinnamon. I used to put the ingredients through the grinder to make a paste. I also used to grate my own horseradish but later I bought the bottled white kind. When the children opened the door for Elijah, Max took a sip of wine from Elijah’s Cup. Max wasn’t a big drinker so he didn’t empty the goblet. When Max ransomed the afikomon, all the children got a little gift or money evenly divided.

“At the end of Passover I packed away the Passover dishes and unpacked my every day ones. Max wouldn’t let me buy bread the night Passover ended because he felt it wasn’t kosher if it was baked during Passover.”

Sukkot

ADELE DESCRIBED HER FAMILY’S observance of Sukkot.[2]

“When the kids were younger Max would make Kiddish in the sukkah at the temple during Sukkot. We had a sukkah at home but Max didn’t think it was kosher enough because the roof was solid, and the stars weren’t visible through it. Years ago in my father’s house, we placed the sukkah on the side of the house. It was enormous! A lot of the people took literally the Biblical commandment, ‘You shall live in booths,’ and so they slept in it even though it sometimes became quite cold at night and rained. Max and I didn’t sleep in our sukkah.

“At the home of Max’s parents, the porch on the second floor became a sukkah. It was kind of like a room with a roof that moved.”

Max was always the first in the synagogue to place his order for the etrog [citron] and the lulav—a green bouquet consisting of the lulav [palm branch], three hadasim, [myrtle branches], and two aravot [willow branches]. These items are ancient symbols of the harvest and are used in a ritual blessing inside the sukkah. The lulav, hadasim, and aravot are tied together in a holder made from palm leaves. Inside the sukkah the lulav bouquet is held in the right hand, the etrog is held in the left, and a special blessing is recited. Then the lulav is waved by pointing it in six different directions and shaking it each time to symbolize G-d’s presence everywhere. Max always brought home his etrog and lulav except on the Sabbath when he left them at the synagogue.

As American as Apple Pie

During World War II, Adele made time to volunteer for the Red Cross as a truck driver. She drove trucks, an ambulance, and even a motorcycle for the Red Cross. In this photo, she is being honored for her participation. Paul remembered a small benefit of his mother’s prowess behind the wheel. One time a large truck was blocking the road and the truck driver was nowhere in sight. So to the astonishment of Paul, Adele got out of their car and moved drove the truck out of her way.

Like father, like son. In some ways, Max and Paul were similar. Max Gass (left) gives an army salute during World War I; (right) Paul saluting on the left with an unidentified friend during World War II.

Max and Adele also integrated American traditions into their household, including huge birthday parties with lots of friends and family. At this birthday party for Janet, Janet and Paul are standing at the back of the table, flanked on the left by Aunt Anna Gass Shapiro and their father, and on the right by their grandmother Lena Kessel Gass, their mother, and Aunt Minnie Gass Alter. Jay is standing (or sitting) directly in front of Lena.

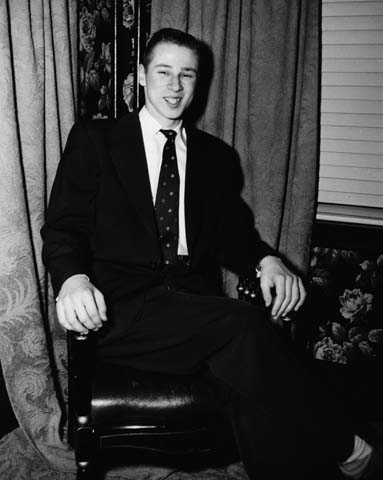

Paul (right) with a friend

Friends of Paul and Janet

Paul, back row 3rd from right and his classmates

JAY

Jay Gass

EVERY HOUSEHOLD HAS ITS SADNESS. In Max and Adele’s case tragedy came early when Jay, their youngest child was stricken with leukemia. Jay was spiritual, giving, and bright. He liked the Yeshiva (a Jewish day school that provided both secular and religious instruction) so his parents sent him there instead of to public school. According to Adele:

“Jay was studious even as young as he was. When the rabbi would say, Go out and play, Jay would reply, Rabbi I have no time. Jay was very spiritual and very giving. He always talked with G-d. Before he became ill, he would say his nighttime prayers, look up in the sky, and murmur, I wonder what death is. I had premonitions with Jay. It used to scare me the way he talked. He always spouted wisdom that was way beyond his age.

“One day, Jay stepped on a piece of broken glass in the bathroom and we couldn’t stop the bleeding quickly. When the wound didn’t heal we took him to the doctor. The doctor tested Jay’s blood and made the diagnosis of leukemia.

“Jay went into the Children’s Hospital for three weeks after his initial diagnosis. I paid for a private room because I stayed overnight with Jay. Everyday he gave me a list of gifts to buy for the kids in the leukemia ward. I would buy the gifts and then take him into the ward so he could give the gifts away. He was in the hospital off and on for transfusions. These stays lasted three or four days at a time. He would say to me, I’m tired I think I need a transfusion. He lived just seven months.

“My brother, Rabbi Samuel Korff, was the Jewish chaplain of the Boston Fire Department. He would bring Jay home from the hospital in his official car and let Jay press the siren.

“I made a mistake—I tried to shield both Paul and Janet from Jay’s illness. When I knew Jay was dying I sent them to my sister in Connecticut. I regret this very much. They came back after shiva and Janet said, I’ll never forgive you for not letting us be with him.”

Paul remembers this sad time, too:

“The only time my father ever raised his hand and let me really have it was one day when I was fighting with Janet. Janet and I usually didn’t fight much but perhaps we were responding to the tension in the house. My father chased me into the garage, hitting me. That’s when I knew Jay was dying because my father said, How can you be like this when your brother is dying? Cherish your sister!

“I stopped fighting with Janet but I didn’t really grasp the meaning of what my father had told me. It was only after Janet and I were sent away to our aunt that I really understood that Jay was dying. I can remember Janet and me crying and feeling like we should be doing something.

“The terrible time came afterward when we stopped doing things together as a family. When Jay was alive we had gone on lots of family excursions. We visited Franklin Field, Franklin Park, places like that. I remember visiting Pioneer Village and my brother stepped on a hot coal or maybe I stepped on it. We always did things as a family, sometimes just the five of us, or sometimes with the extended family, too. We visited my mother’s family in Dorchester and my father’s family at 27 County Road. It was always family. After Jay died, all the outings stopped. The magic just left. My father started having nightmares. He kept Jay’s toys by his bed and near his desk. We maintained the routine of seeing relatives but 27 County Road was never the same after Jay’s and my grandmother Lena’s deaths.”

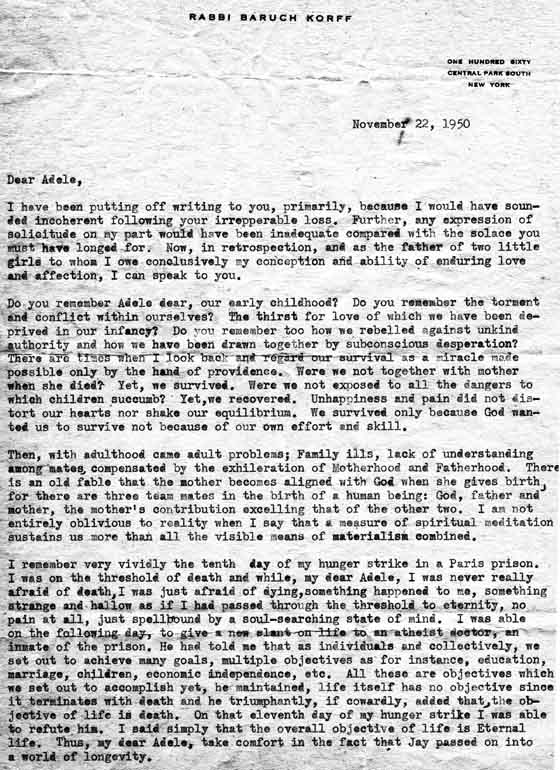

Condolence letter written by Baruch Korff to Adele after the death of Jay. The second page of the letter is missing

Jay died in 1950. Max would have liked to have more children but Adele became quite ill after Jay’s death and the doctor advised against another pregnancy.

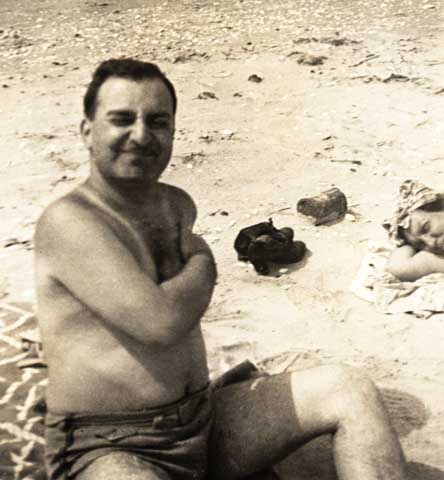

Max enjoying a day at the beach, probably before Jay’s death.

Janet

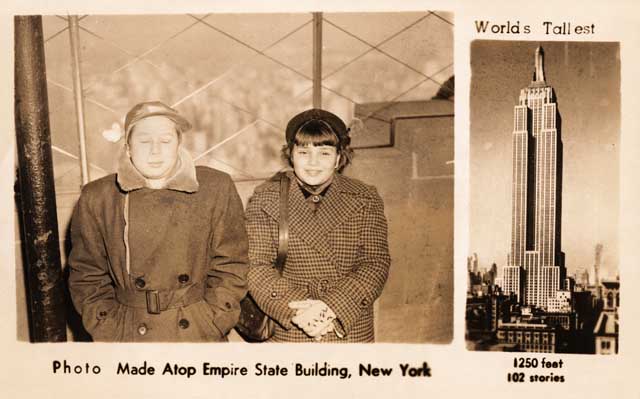

Paul and Janet atop the Empire State Building several years after Jay’s death when the family had adapted to their new life without Jay.

Janet and Paul

Paul and Janet in their teen years

BY THE TIME PAUL AND JANET REACHED adolescence, the family had regained its equilibrium and their teenage years were happy ones in the Gass household. The big kitchen in their home in Chelsea served as a focus of family activity and provided a warm, cozy ambience for the many visiting friends and relatives. Adele seemed to cook continually, preparing everything from scratch. She earned a reputation among friends and family as a great cook and good baker. Her soups were especially admired. She loved to nurture children, making sure all their physical needs were met.

All the members of the family liked to congregate in the kitchen, talking and eating. Everybody interacted with each other. Paul had a huge appetite and would down enormous hero sandwiches concocted from rye bread, pickles, coleslaw, and every kind of kosher meat imaginable. He was also big on ice cream. He would take a half-gallon container of ice cream, cut it in half, and eat out of the carton.

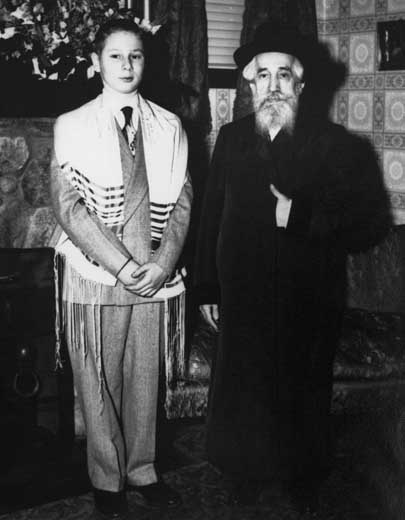

A Bar Mitzvah is major milestone in any boy’s life, but especially for the oldest grandson of a grand rabbi.

Bar Mitzvah boy Paul Gass with his grandfather Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff

Front: left to right: Betty Korff Berkowitz, Adele Korff Gass; second row: Pauline Korff Kerber, Etta Korff, Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff, Paul Gass, Janet Gass; Back: Walter Berkowitz, Max Gass

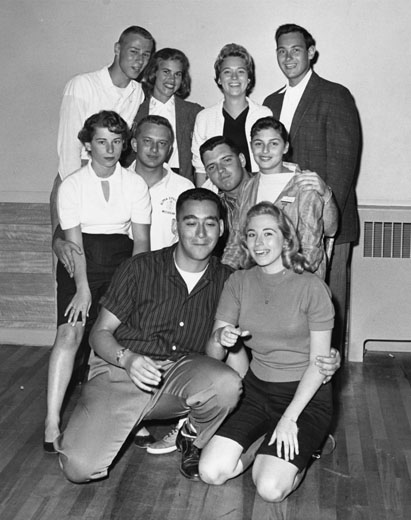

The Bar Mitzvah celebration was quite lively with so many of Paul’s cousins and friends in attendance. Front row, far left: Joe Korff and Janet Gass; third row, 5th from left: Paul Gass

Adele enjoyed hosting small family dinners too. Left to right: Minnie & Joe Alter; Ida, Jonas & Judy Ullian; Max, Janet & Adele Gass; Sam & Nesha Korff; Shiela & Sam Fish

Both Janet and Paul were active teenagers with lots of friends. They were constantly on the go, roller skating, playing stickball, and bowling. They especially enjoyed just hanging out with the kids they liked.

Janet (seated near center) and her friends

Paul (back row, far left) with his crowd

Paul and friends

Janet was attractive with excellent taste in clothing. She listened to records constantly, loved to throw slumber parties, and championed the underdog. The phone was always ringing for her. She loved to shop and her taste in jewelry was conservative.

Janet was not a rebellious adolescent. According to her mother, she was very respectful, sincere, and straight forward.

Janet was a cheerleader in school, bubbly in personality with a strong, hearty laugh. She was bright but not pretentious. She had a passion for Spanish and Latin, and even asked her parents to send her Spanish and Latin texts one summer when she worked a counselor at an overnight camp.

Janet enjoyed being a camp counselor

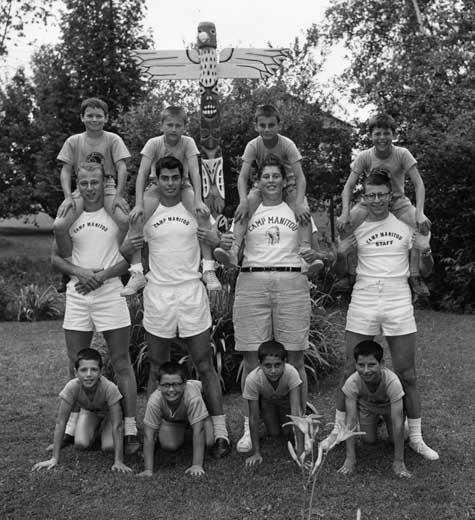

Paul as a counselor-in-training

Paul far left, standing with camper on his shoulders

Paul (far right)

Chelsea High School

In 1957, Janet graduated from Chelsea High School and enrolled in Colby College, then a two-year institution in Maine. After graduating in 1959, she moved to New York City, where she held a day job and attended New York University (NYU) in the evening. She was awarded her college degree from NYU in 1962.

Janet and her prom dates

Janet receiving her college diploma

Six months earlier, on October 16, 1961, Janet had married Laurence (Larry) Dayton. It was his second marriage and Adele had a premonition that the marriage would not work. Paul shared her apprehension. Although Janet did not heed Adele’s advice to break off the engagement, Adele provided her with the fairy-tale wedding that Janet had dreamed about. According to Paul:

“My parents didn’t have money, yet they threw a very expensive wedding for Janet. To pay for it, they had to borrow against the cash value of an insurance policy.”

Janet and Larry

Janet and Max at her engagement party

Mr. and Mrs. Larry Dayton

The newlyweds moved to Amherst, Massachusetts, where Larry was a graduate student in a doctoral program and Janet worked in the campus’s Hillel office to support them. Janet wanted children but Larry did not. For three years she tried to make the marriage work but the couple couldn’t resolve their differences. Janet walked out once but then returned. The separation became permanent when she discovered Larry was interested in someone else. Initially she took another apartment in Amherst but six or seven months afterward she returned to her parents’ home, feeling like she had failed at life. In 1963, Janet died of a broken heart.

Paul remembered the shock of Janet’s death on the family:

“I lived in the same house with Janet and it just blew my mind that I didn’t know what was going on although I had noticed that she stopped taking care of herself. I never really knew my sister and she never really knew me. She didn’t have any support mechanisms in place when her marriage failed.”

The loss of two of his three children devastated Max. He became quieter and passive after Janet’s death. Adele was able to share her grief with friends and family. Max never discussed it but Paul observed the effect on him:

“The death of two of his children was very hard. When my brother died my father kept all his toys around. When my sister died he had all her records and different things around for years and years.”

The house on Fremont Avenue held too many painful memories, so two years after Janet’s death, Max and Adele sold it and moved to a house nearby on Highland Avenue in Chelsea.

Adele seemed to have had only one regret about her relationship to Max. It pertained to a thoughtless comment to a friend that Max overheard. Adele’s voice was filled with sadness when she described what happened:

“Max and I were married on the 20th of the month. For many years on the 20th of every month Max would write me a poem and give me a little gift. Then one day I said to a friend, Can you imagine a man still writing poetry to his bride after all these years. He never did it again after that.”

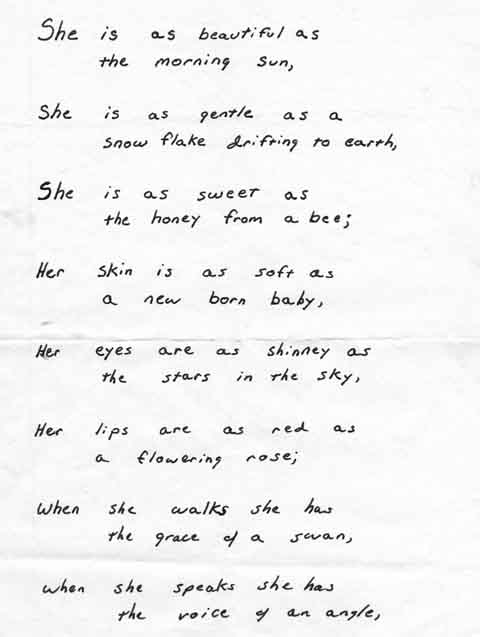

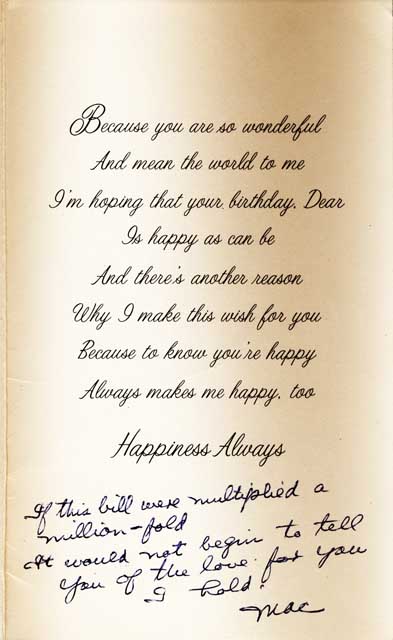

One of Max’s poems for Adele

Max, however, continued to express his love in writing on her birthday and their anniversary.

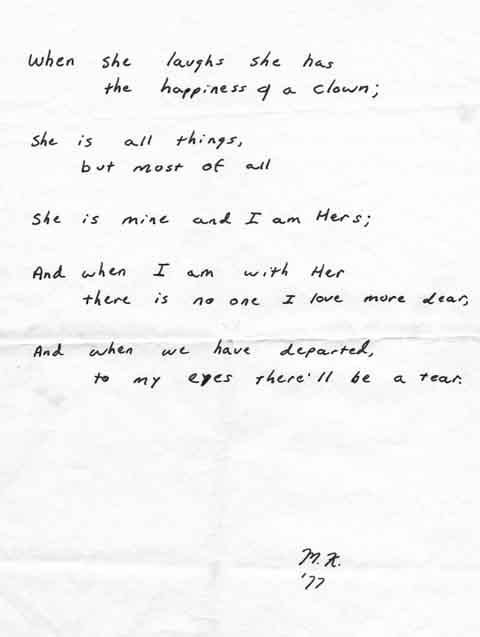

An anniversary letter to Adele

Max must have enclosed some money with this greeting card.

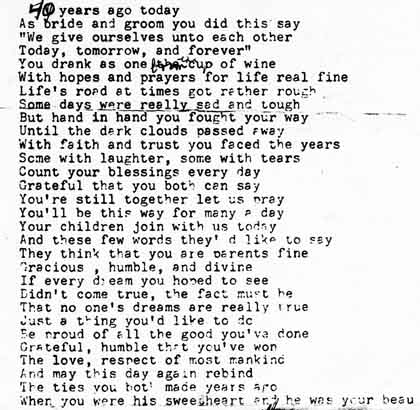

An unidentified well-wisher prepared this poem in honor of the Gass’s 40th wedding anniversary.

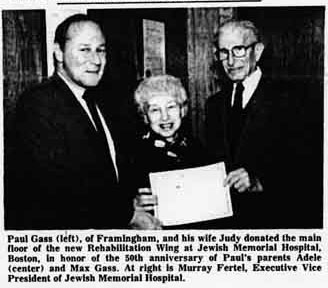

In honor of Max and Adele’s 50th wedding anniversary, Paul and his wife Judy donated the main floor of the new rehabilitation wing of Jewish Memorial Hospital.

Courtesy of the Jewish Reporter, Framingham, MA

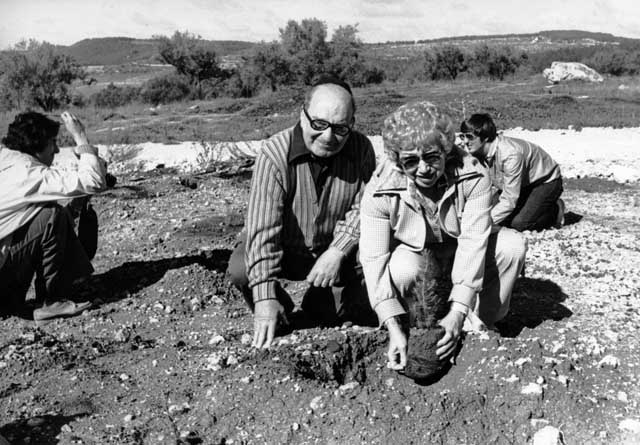

Max and Adele loved to travel, and one of their favorite destinations was Israel.

Max and Adele participating in tree planting, an event sponsored by the Jewish National Fund. For more than 100 years the Jewish National Fund has been planting trees in Israel (in 2005 the total number was in excess of 240 million trees), transforming barren dessert land into lush forests.

Max removing his shoes outside before entering a Jerusalem mosque

Max and Adele in Jerusalem

Max and Adele standing in the ruins of a huge mosque from Turkish times in Ramle, Israel

Max at the Wailing Wall

Taking the Queen Elizabeth II to Israel, despite terrorist threats, 1973

Reprinted courtesy of the Chelsea Record

Max and Adele dressed for a costume ball aboard a cruise ship. Perhaps these photos were taken on the Queen Elizabeth cruise.

Adele returned to Russia for another visit.

When Adele visited this Moscow synagogue in the 1960s or 1970s she met some congregants from Novograd Volynsk who remember her parents.

This photo of Adele was probably taken on her second trip to Russia.

The Fiftieth Wedding Anniversary Celebration

Max and Adele were fortunate enough to be able to celebrate fifty years of marriage. Paul and his then-wife Judy, hosted a large party in their honor at the Royal Sonasta Hotel in Cambridge, Massachusetts on Sunday, January 4, 1987.

Max and Adele at their 50th wedding anniversary celebration

Max and Adele with their son Paul, daughter-in-law Judy, and granddaughters Lisa and Leslie

Food always plays a prominent role at parties hosted by Jewish families.

View of Boston’s Museum of Science along the Charles River, as seen from the Royal Sonasta Hotel where the anniversary party was held

Family of Adele’s brother of blessed memory, Rabbi Samuel Korff: Front: Harriet, Nesha, Phyliss; back: David and Joe

Paul giving a speech at his parents’ 50th anniversary celebration

Max’s nieces and nephews: Nancy, Judy, Ida, Mona; back: Lenny, Jeff, Fred, Greg, Mark

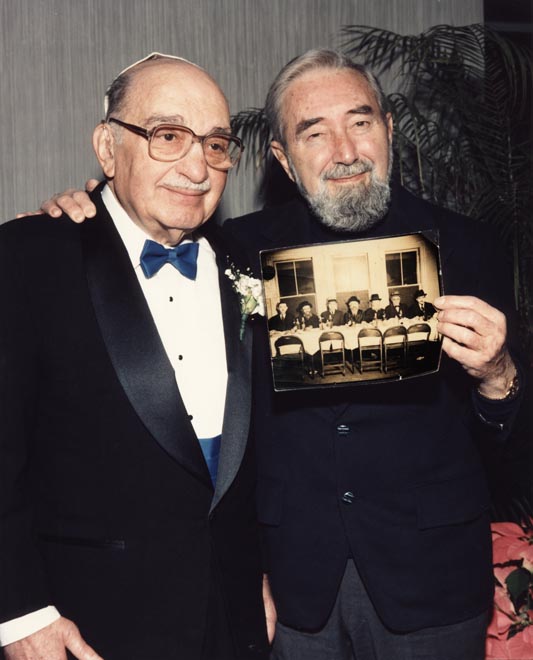

Max and his brother-in-law Rabbi Baruch Korff, holding a photo take at Max and Adele’s wedding 50 years earlier

Father and son

Max and Adele with Paul and Judy and their daughters Leslie and Lisa

The whole mishpocha (almost). Front row, sitting, left to right: Lenny and Nancy, Ellen and Jack, Jonathon; 2nd row, standing: Julia, Julie; sitting: Polly, Betty, Leslie, Lisa, Adele, Max, Jordan (kneeling); 3rd row: Baruch, Monica, Max, Molly, Lisa (standing sideways), Ida Gass, Sarah Gass, Nesha Korff, Susie, Mottie, Phyliss; 4th row: William (Sonny), Judy & Paul, Fred (partially obscured), David Korff, Joe, Mike, Harriet, Judy

[1] In Ashkenazi tradition, children are named for relatives who have died, and they are never named for people who are living. In this way names are handed down through the generations. Adele was named Udel after the only daughter of the Ba’al Shem Tov. Max was named Matityahu Aharon (Mattes for short) after his maternal great-grandfather.

[2] According to the Torah, the firstborn son of a mother belongs to G-d, and is expected to dedicate his life to serving G-d. To free the child from this obligation, the child is redeemed by having the father pay a fee of five silver shekels (five silver coins) to a Kohen, (a Jewish priest) If the child is a Kohen or Levi, (inherited positions through the male line), the family foregoes this ritual because Kohens and Levites were obligated to serve in the Temple.

[1] Tefillin were created to carry out the commandment to place a sign upon the hand and forehead as a reminder to fulfill G-d’s commandments. They are composed of two parts. The tefillin shel yad is wound around the arm and hand. The tefillin shel rosh is placed on the head. Each part has a bayit, a box, made from the skin of a kosher animal in the shape of a perfect square.

The shel yad has one compartment; the shel rosh has four separate compartments and has the Hebrew letter shin on two sides of it. In each box, written on parchment, is one set of four Torah portions dealing with the mitzvah of tefillin:

- ‘And this shall serve you as a sign on your hand and as reminder on your forehead–in order that the teachings of the Lord may be in your mouth–that with a mighty hand the Lord freed you from Egypt.’ (Exodus 13:9)

- ‘And so it shall be as a sign upon your hand and as symbol on your forehead that with a mighty hand the Lord freed us from Egypt.’ (Exodus: 13:16)

- ‘Bind them as a sign on your hand and let them serve as a symbol on your forehead.’ (Deuteronomy 6:8)

- ‘Therefore impress these my words upon your very heart: bind them as a sign on your hand and let them serve as symbol on your forehead.’ (Deuteronomy 11:18)

For the shel yad the portions are written on a single piece of parchment; for the yad rosh each portion is written on a separate parchment.

“The tefillin are placed on the arm and the forehead in a prescribed manner with the saying of prescribed blessings. One long strap knotted in the shape of the Hebrew letter yod is attached to the shel yad. This strap is shaped in the form of a noose so it can be tightened on the arm. Another long strap knotted in the shape of the Hebrew letter dalet is attached to the shel rosh. It forms a circle which can be adjusted to fit the head.

[2] The tradition of sprinkling salt on bread has it roots in ancient times when our forefathers salted all their sacrifices. According to the Talmud, “A man’s table is like the altar,” so traditional Jews salt their bread before eating it.

[1] Passover is observed for eight days, except in Israel where it is observed for seven. The highlight is the sedar, where the Exodus story is retold through a sequence of prayers, readings, activities, songs, and feasting outlined in a book called the Haggadah. A sedar plate holding symbolic Passover foods is placed on the holiday table. These foods are (1) Maror–bitter herbs (usually horseradish)— symbolize the bitter lives of the Hebrew slaves in Egypt. (2) Charoset–a mixture of fruit and nuts–is a reminder of the mortar the Israelites made for their masters. (3) Zero’a–shankbone (usually a roasted lamb bone)–symbolizes the paschal lamb eaten on Passover by the Hebrews when the Temple stood in Jerusalem. (4) Karpas–a green vegetable that is dipped in salt water–suggests springtime and rebirth. (5) Baytza–roasted egg–represents the sacrifices brought to the Temple at festival times. (6)Chazeret–lettuce, radish or another bitter vegetable–symbolizes the bitterness of slavery.

Three pieces of matzah are placed on the sedar table. Two of the pieces depict the loaves of challah placed on the Sabbath or festival table. The third represents the Passover holiday. During the sedar the leader breaks off a piece of the middle matzah and hides it. The children hunt for it later and ransom it for a gift. This matzah is known as the afikomon (Greek for desert) and is the last food eaten at the sedar meal.

A goblet filled with wine is also placed on the table. It is Elijah’s cup, a symbol of hope that the prophet Elijah, the harbinger of the Messiah, will appear that night and usher in the Messianic age.

[2] Sukkot, the Festival of Booths, is one of three Pilgrim Festivals. Passover and Shavuot are the others. It is celebrated for seven days (although some people have an eight-day celebration). In ancient times Jews traveled to Jerusalem by foot to celebrate the holiday. They brought a portion of their fall crops to give to the priests. Some of the offering was used as a sacrifice at the Temple, the rest was kept by the priests to feed their families.

The sukkah, the primary symbol of Sukkot, is a temporary dwelling, a reminder of the shelter Jews slept in while wandering in the wilderness after fleeing Egypt. Sukkahs are also reminiscent of the huts the Israelites constructed near their fields at harvest time.

Contemporary sukkahs can be made from a variety of materials–wood, plastic, canvas, etc. The main requirement is that the roof be sufficiently dense to provide more shade than sunlight during the day but not dense enough to obscure starlight at night.