THE CAREER CHOICE of Max Gass was almost predetermined at birth. As the only son of hard-working immigrants, Max was groomed to be a businessman. His father, Samuel Gass, had lived the classic rags to riches story, arriving penniless in the New World, and making a success of himself, first in the rag recycling business and then in shoe manufacturing. Max, however, did not find material success in the business world nor did it satisfy him intellectually or emotionally.

When Max was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts, in 1911, his father was still working in the rag business. The family lived in a ‘three-decker’ on Orange Street in Chelsea, above the apartment of his maternal grandparents. Max’s birth was followed over the next eleven years by the arrival of four sisters. In the early 1920s the family moved to a large house at 27 County Road in Chelsea, a veritable mansion compared to their former cramped quarters and a tangible symbol of Samuel’s success.

Early on, Max showed a strong aptitude for both scholarship and religion. His father hired Rabbi Bernard Dubrow, an immigrant melamed (teacher) to home tutor Max and his sisters in Hebrew.[1] After these lessons ended Max did not receive additional formal religious training. Instead, through persistent and life-long study he became learned in Torah and Talmud and taught himself how to chant prayers as competently as a professional cantor.

In 1925, Max graduated from Chelsea High School. Beside his senior picture in the Beacon, the high school yearbook, is the quotation, He lived at peace with all mankind; in friendship he was true. He went on to Boston University where he majored in law, with a minor in economics and social science. He received his Bachelor’s Degree in Laws in 1930, and his Master’s Degree in Laws degree in 1931.

Chelsea High School, Max’s alma mater, was also the school that his children, Paul and Janet, later attended.

In 1921, Samuel Gass had started Lion Shoe Company in Lynn, Massachusetts, with his brothers Morris and Nathan Gass, and his wife’s brother-in-law Abe Gootman. As a young man Max worked in the family business. After Lion Shoe closed in 1940, Max became the right-hand man of his father, assisting him with business matters pertaining to the family’s investments and real estate holdings. Samuel Gass helped Max begin a new business venture, the Liberty Wool Stock Company, in partnership with Max’s second cousin, Nathan Cutler, and brother-in-law, Jonas Ullian. The business was located on Second Avenue in Chelsea, and three of Max’s sister helped out. It is apparent from correspondence between Samuel and his offspring that Sam was calling the shots.

Read Samuel Gass’s correspondence

Rabbi Baruch Korff, Max’s brother-in-law, described the relationship between Max and his father:

“Mattes was very devoted to his father, extremely devoted. I’ve never met a son more devoted. If you had told him to be in a harness and be the horse, he would be the horse.

“Max once said to me, ‘You know where you have honor thy father and thy mother? It’s the only commandment where the reward is given right there. Honor thy father and thy mother that your days may be long on earth. Of all the Ten Commandments, this is the only one in which you are given immediate reward.’

“He really was a believer that G-d will prolong his life if he honors his father and mother. And beyond that, he was genuinely fond of his father. The father had a severe case of arthritis, and would wear half gloves to cover up the warts and the hands. Mattes would look at those hands and say, ‘This is what saw me through college’.”

FAMILY COMMITMENTS WERE CENTRAL to Max and Adele’s marriage. Sam Gass had placed some of his assets in the form of securities and real estate in his wife’s name. After she died the assets were transferred to the newly created Lena Gass Family Trust. One third of the trust’s income was paid out to Sam Gass. The rest was evening split among his five children. Following Sam’s death, Max and his brother-in-law Joseph Alter (Minnie Gass’s husband) became the trustees. They divided the money and stocks among the children, leaving in the trust the real estate, a block of stores which Max Gass managed.

Baruch Korff, Max’s brother-in-law described Max’s business ethics succinctly:

“Mattes was the epitome of honesty and integrity. He wouldn’t take a penny that belonged to his sisters.”

Max applied his morality to his interactions with his tenants. As Paul Gass remembered:

“The rents on the properties were too low. My father kept them low, because, he said, You only took what you needed. If you didn’t need a lot of money, then you didn’t charge a lot of money. My father used to keep all the books, which were really meticulous. To see the books was just absolutely unreal, because pennies would be split.”

Max’s concept of family extended to Adele’s brothers and sisters, and he enjoyed socializing with them. Left to right: Betty Korff Berkovitz, Max and Adele Gass, ???, Nathan Korff, Max Korff (in Navy uniform)

Although Max made a living in the business world all of his life, he lacked the business acumen of his father and likely would have been happier and more successful if he had become a rabbi or followed another career path more in tune with his spiritual needs. Given a business problem, when all else had been tried, Max Gass sought a spiritual solution. A story told by Max’s first cousin Harrison Gass, who worked with him at Lion Shoe, illustrates this:

“Max was in the shoe factory, he’d been there for a few years, and we had a problem, a pattern problem. You have to have a design [for a shoe], like when you make coats, shoes, and things have to fit. And everything was fine except the shoes when they got out at the end, they didn’t fit.

“So we had all kinds of experts he brought in—we brought a guy from New York to figure what was wrong—and still it wouldn’t fit. And it was a big important shoe at the time. Finally we decided, well I guess we better throw it out.

“Max says, ‘No, don’t throw it out. Maybe I can help.’

“‘Good, what you gonna do?’

“And he said he’s going to write a kvittel. A kvittel is a little note you write if you got a serious problem in life. You write your problem and you fold it up, and then you find some holy place, preferably in the cracks of the holy wall in Jerusalem, and you stick it in there. And somehow miraculously the answer would come back. So he’s going to write a kvittel and take it to the Grand Rabbi Korff.”

As an observant Jew, Max chose to work in businesses where he would not be required to come in on the Sabbath or on Jewish holidays. Throughout his adult life he was actively involved in the Jewish community, occasionally serving as cantor at the Orange Street shul in Chelsea, and in the Winthrop synagogue, writing and delivering his own prayers. According to his son Paul:

“My father and his cousin, Hymie Razin, used to compete to be the cantor at the Orange Street shul. Hymie would get to be cantor during the High Holidays and Max would get to be cantor on Saturdays.”

Max also served as a chaplain of the Noddles Island Lodge of the Masons in Boston.

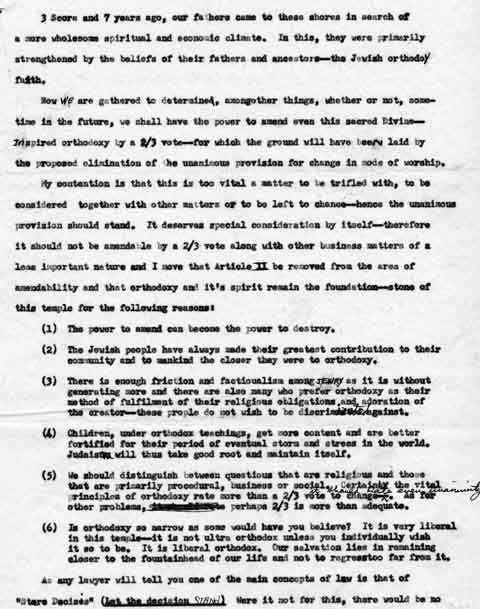

Max was vehemently opposed to any deviation from the Orthodox form of worship at his synagogue.

Max’s granddaughter Lisa Gass recalled that if you expressed interest in some aspect of Judaism it meant a lot to Max. He loved to take the time to discuss and explain the intricacies of his faith. When she was 13, Lisa talked to Max about her coming Bat Mitzvah. She told him that if she was going to do it she wanted to go all the way, to put on the tefillin and the tallis. And Max was against it because, in Jewish tradition, only males did these things.

Max then went to the Talmud and consulted rabbis trying to find a source in Jewish law where it stated that women were prohibited from participating in this way. When he was unable to find such a prohibition, he took Lisa to a Jewish bookstore in Boston and bought her the tefillin and tallis himself. Even though Max Gass was very much a traditionalist, he was willing to go against tradition if Jewish law did not uphold it.

Max’s other granddaughter, Leslie Gass shared her recollections of Max:

“Most of my memories are of him praying, reading, and talking about Hebrew school. I especially remember him at Passover. We’d have twenty or thirty people all sitting around this huge table in my grandparents’ small apartment. He would be at the head of the table reading all the prayers in Hebrew. And sometimes people would start talking and he’d crack a little joke. That was when he got older—at first he was more strict about the Seder. There hasn’t been a Passover like that since he died.”

Max’s Commentary and Analysis

AMONG MAX’S GASS PAPERS was a folder labeled Commentary/Analysis, which contained treatises on a variety of subjects. One essay written in 1960 was titled “An Analysis of Ford Motor and General Motors” and over the course of 11 pages delved into the importance of the newly introduced compact car lines (Corvair by GM and the Falcon and Comet lines by Ford) in meeting the need of the American car-buyer for economy in operation and purchase price. Others issues Max addressed were competition from European car makers, building factories abroad to benefit from cheaper labor conditions, the non-automotive operations of Ford and GM, and a comparison of the book value of the two car companies. In the end he concluded:

“…Ford has earned more per common share and has paid out more in dividends per common share than General Motors. It is true that Ford pays out in dividends a smaller percent of what they earn per share than General Motors. However, the main attraction of Ford is the actual dividends received, plus the bright opportunity for capital gains and increase in dividend.

“The fact that Ford has relatively fewer shares than General Motors spreads the earnings on fewer shares. Ford could easily have an upside potential of 100-110—in which event a stock split might be considered possible. General Motors could reach the middle fifties without too much difficulty and is always a good investment, but hasn’t the speculative attractiveness for 1960.

“However for the long term investor, General Motors represents solid value because of its large operations—is more diversified and is not too dependent on the car business, which historically has, at times, proven itself cyclical.”

In “How to Plan and Pay for the Safe and Adequate Highways We Need,” written circa 1974, Max recommended the need for bold, futuristic thinking:

“In a growing country like the United States, planning ahead twenty-five years for a highway system which may then be adequate is not unreasonable and certainly within the realm of attainment. In fact, not to plan far enough ahead would mean traffic congestion and the future deterioration of the safety record we now enjoy…If we build roads only to have to rebuild them when the traffic demands it, we will run into the unfortunate experience of states like Connecticut and New Jersey, which need to revise their highways and make them wider and more adequate when a bold, original plan would have obviated all that for less money.

Max recommended the building of more circuitous and roundabout routes as “they involve the buying up of less costlier land than the buying up of buildings and land in the heart of the city or in the outskirts, thereof which puts money into real estate which is intended in the first place for the building of roads.”

Although he could not have predicted the terrorist attacks by Islamic extremists in the 21st Century, Max recognized the need for adequate civil defense funding and planning in major cities. He addressed the need for roads that could handle mass evacuations from large cities during an emergency:

“Bearing in mind the vulnerability of large cities in this atomic age, roads must be built and existing roads must be improved to create and supplement new means of egress from these cities in the event they [city dwellers] have to unscramble hurriedly to the country in the event of hostilities.”

He reasoned that by joining the cause of civil defense with highway development the needs of both would be better met: “…better roads mean better handling of disaster causalities.”

As part of his civil defense plan, Max suggested that states construct large parking garages in cites which could be used for parking during normal tines and be converted into makeshift hospitals during an emergency:

“…parking lots with underground space for cars in normal times, would take away the heavy parking from the streets, and in times of disaster could serve as places for movable hospitals and shelters…where people needing prompt attention would not die… because normal hospital facilities [were] either destroyed …or were never meant to care for the number of cases that would eventuate from disaster conditions.”

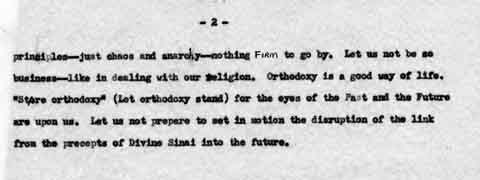

During World War II, Max took a course in civil defense and served as an air raid warden in the city of Chelsea. Perhaps these experiences made him more cognizant of the vulnerability of urban areas to enemy attack and helped him link the need for proper highway design with civil defense planning.

He also suggested the decentralization of industries “so as not to present some enemy with an over-attractive target.” Additionally he predicted that the long term result of such a plan would be “the gradual infiltration of the industries into agricultural areas so that employment will be more evenly spread throughout the country.” As part of his plan for decentralization, Max advocated the building of atomic power plants as a source of energy.

To pay for the building of a proper highway system, Max suggested that the diversion of funds from the gas tax be stopped. He recommended that the U.S. government sell “one-half of its utility interests and use the proceeds for building highways where needed…” He also proposed the federal government “issue long-term bonds payable a little each year…and it could issue short-term bonds providing that the money that the state collects for the gas tax pay off these short-term bonds as they mature…” He was not a fan of toll roads.

“Much has been mentioned about the benefits of toll roads as not being an immediate expense but one that the public pays for gradually. However, there is too much inefficiency and loss of receipts in this method. It is best wherever possible to face the pain of the expense of building the roads—let the [federal] government and the regions of states bear their proper portions of debts…”

He concluded:

“In time of calm, better roads are necessary to enjoy scenic travel and for safer driving. But in times of emergency, when this country must flex its muscles and fast so that the compact strength of the country will be felt from every nook and corner of the land, we owe it to ourselves to have the safest and most adequate highways possible or, in this world of struggle and tension, we might wish we did.”

Max’s eight-page essay on “Objective Oblivion” written in the wake of World War II, dealt with the threat of nuclear war, the challenges of capitalism, the Russian challenge for European domination, the Marshall Plan, and the need to reach out to China. This was not an optimistic piece of writing:

“As the world treads on the doorstep of the Atomic Age, the forthcoming tug-of-war for world political power shows that the world has no objective worthy of the name. One objective that has never been attained for long is peace. And well may one ask, “What objectives are worthwhile, if peace, the greatest of all objectives is unattainable?” The different political systems are unable to translate post-war chaos to universal understanding nor can it change uncertainty to a reasonable predictability. All means at civilization’s command are inadequate to achieve peace. We must therefore contemplate the dread alternative of further friction and possible oblivion.”

Max enjoyed writing long letters to editors of newspapers. One of his favorite themes was the threat of communism. There is no evidence showing that any of these letters were published. Here is a sample from a letter sent to the editor of the New York Times, dated January 7, 1948:

“…Our policy toward Russia is not firm enough. If it were, the wave of aggressions would have ceased long ago. Why are there so many focal points of unrest all over the globe? They cannot all be due to internal conditions, which are unfavorable, and if they are, they would have been healed long ago if there were no obstructionism that prevented the normal flow of trade. All know that the aftermath of war is very bitter but certainly not so bad that people are looking for more war. The unrest, coming as it does, all at once, suggests a common source of irritation. Why are we not assisted by Russia in feeding Europe? Or must a European sell his soul to eat? And if Russia hasn’t the food to feed Europe with, why doesn’t she stop bragging about the superiority of her system over capitalism? The United States has done its fair share. Strong leadership in our country would stop silent aggression and we would eventually have a world at peace…”

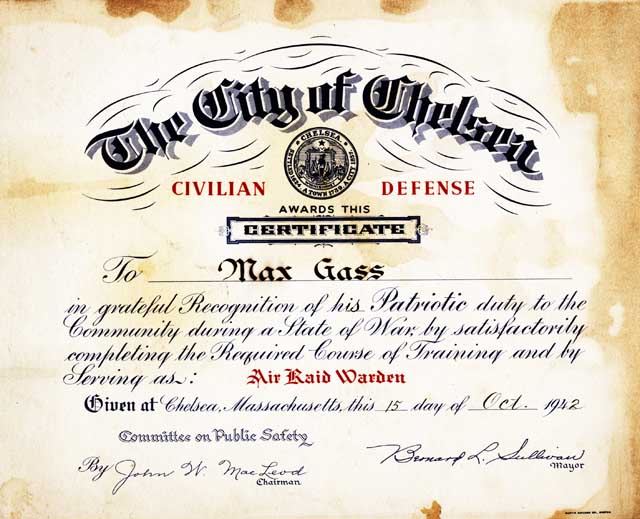

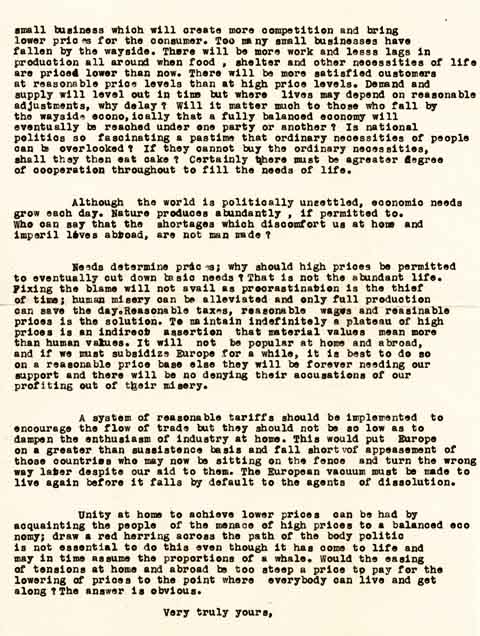

Concern about the cost of living led Max to write this letter to the editor in 1947.

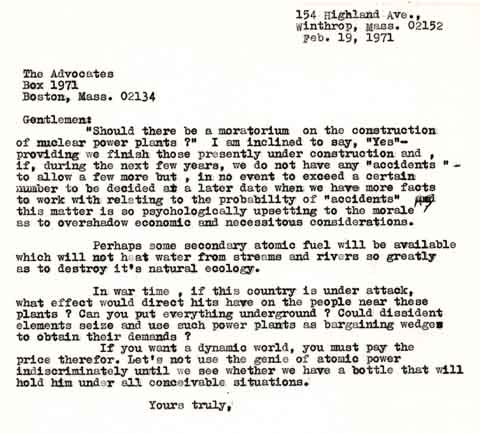

Max was perhaps 30 years ahead of his time in his concern about nuclear power plants being targets for America’s enemies.

Letters to Businesses

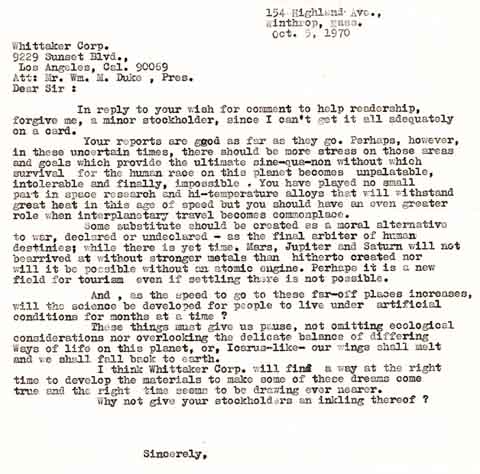

MAX SHOWED NO HESITATION in telling corporations how to better run their businesses. Below is just a smattering of the many letters Max wrote dispensing business advice.

Max the Inventor

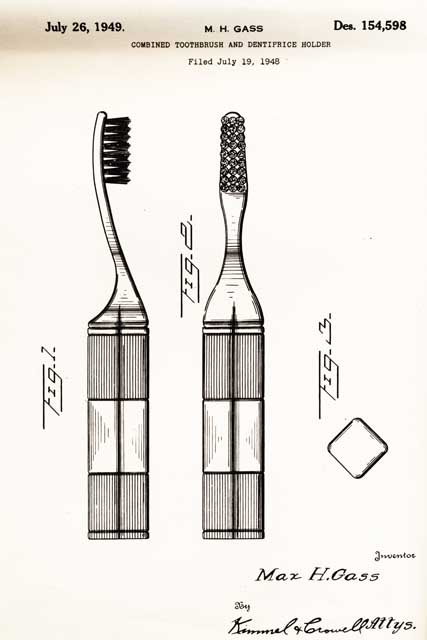

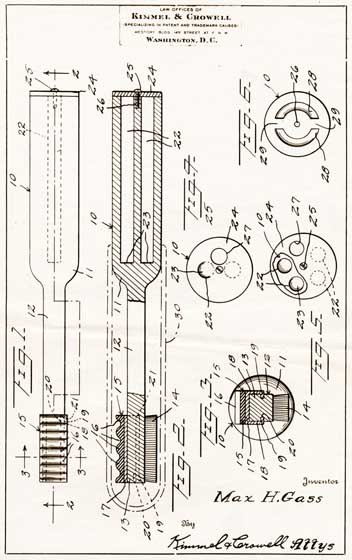

Max Gass had a creative imagination and over the course of his lifetime invented a number of devices and games. One of these he took all the way to patent—a toothbrush, which included a gum massager, a sterilization compartment, and a hollow handle for holding pellets of tooth cleaning powder. This design was patented in 1949.

Max’s patent for a combined toothbrush and dentifrice holder

Other inventions described in his papers included a can-opener cleaning kit, a Roll-It-On glue stick, and a tilted invoice box. This last Max described in a letter to a Mr. David James, from whom he sought funding for several of his inventions:

“Where I work we have a metal box of six compartments (open in front) wherein go invoices of the orders. Sometimes an invoice falls out, occasioning delay and problems due to it’s becoming lost. I have often thought that if the same metal box could have the slots tilted downward at an angle, the invoices could not fall out even if the fan were going full force in the summer on a hot day.”

Both glue sticks and tilted invoice boxes are now available in any office supply store, although Max Gass himself was not able to carry these ideas all the way to patent and manufacture.

The games Max Gass invented are unique in that through them Max sought to convey values and improve society. A game show designed for television called Make Sense involved sayings broken into their component words. Various clues were given to a panel of players to help them reconstruct the sayings, working against each other and against the clock. As Max described the game, its purpose was “for entertainment and to promote learning by restating some wisdom that these times are sorely in need of.”

Another game, Moving Basketball was a permutation of the game of basketball. Max thought it was unfair that tall guys could stand in front of the basket and score easily while little guys couldn’t win. To make the game more fair, he designed a moving basket. `This involved an electronic arm, which moved the basket slowly in a half-circle, right to left, and back again. According to Max:

“Shooting at a moving object should modernize the game in an age when take-offs from earth to the moon have become commonplace. It should bring basketball up-to-date with a Space Age of projectiles launched from a moving Earth trying for a landing on other moving bodies in the Solar System. With this innovation, the game should be more of a challenge for six and seven- footers, and give some of their shorter competition a more even chance to win.”

Max’s hope was, that if he could find a backer and this invention took off, “The new game would be 50% owned by the public. 50% of the profits, after expenses, would go to rebuilding slums in big cities, and provide scholarships for needy youths.”

It is characteristic of Max Gass that his dream was never just to enhance his personal fortune, but always to contribute to society and bring inspiration and higher values to humanity.

Max did not just sit on his ideas, but carried on a brisk correspondence with patent attorneys, television executives, financiers, and the research and development departments of major corporations, trying to find support, funding and a possible market.

Max the Writer

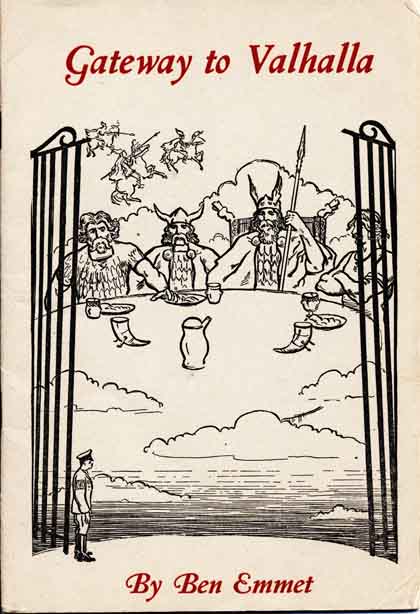

WRITING WAS PERHAPS Max Gass’s favorite occupation, and as he did with his inventions, he sought actively to get his ideas out into the public forum. Max sent letters and poems to magazines and newspapers, manuscripts of plays and novels to publishers. After numerous attempts to find a commercial publisher for his play, Bacchus is Risen, he self- published it with Bruce Humphries, Inc. a Boston publisher, and the book was assigned a copyright by the Library of Congress in June 1941. A second play, Gateway to Valhalla was published in 1945 under the pseudonym Ben Emmet, also by Bruce Humphries, Inc. Following its publication Max sought for years to get the play produced, sending copies to numerous radio and movie studios, as well as theater production companies and workshops.

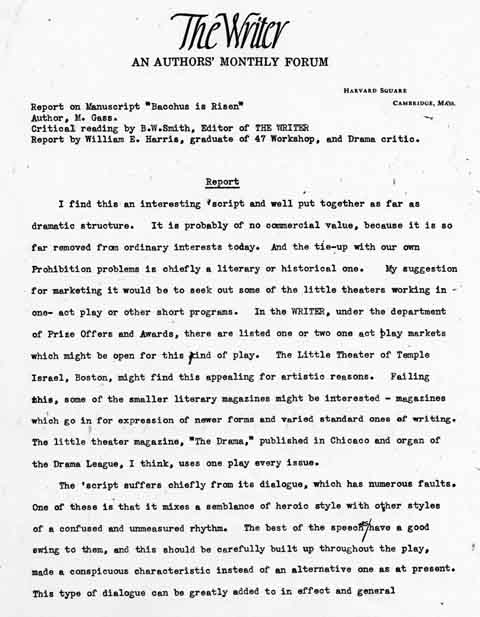

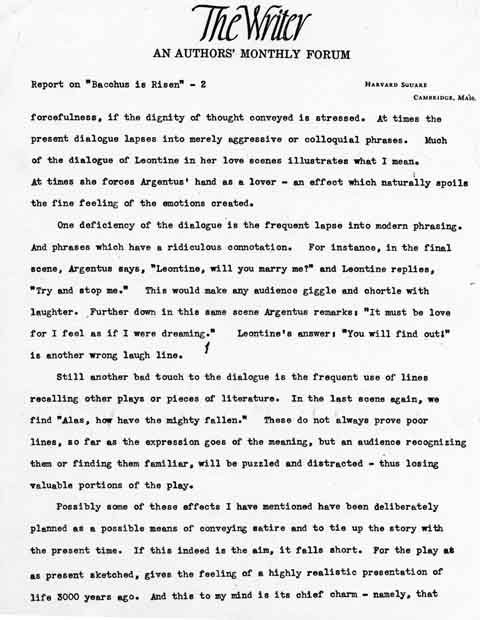

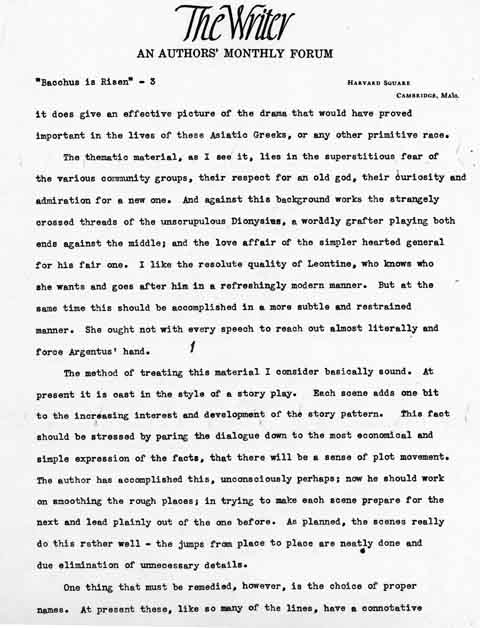

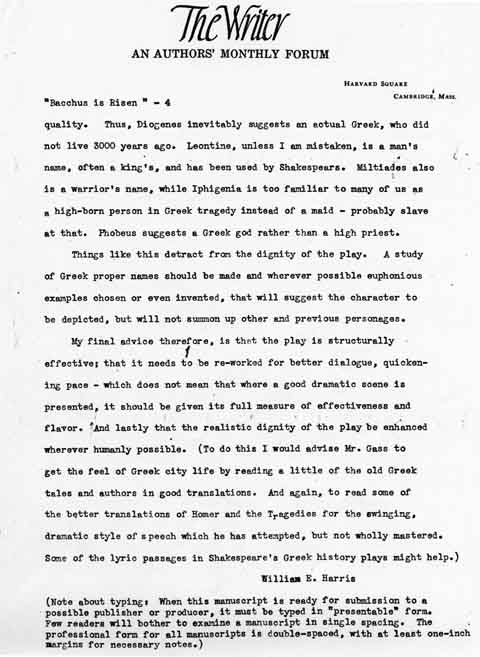

Max had his play Bacchus is Risen professionally critiqued, a service for which he liked played a fee. The analysis of his writing provides insight into Max’s lack of success in finding a publisher for any of his writings.

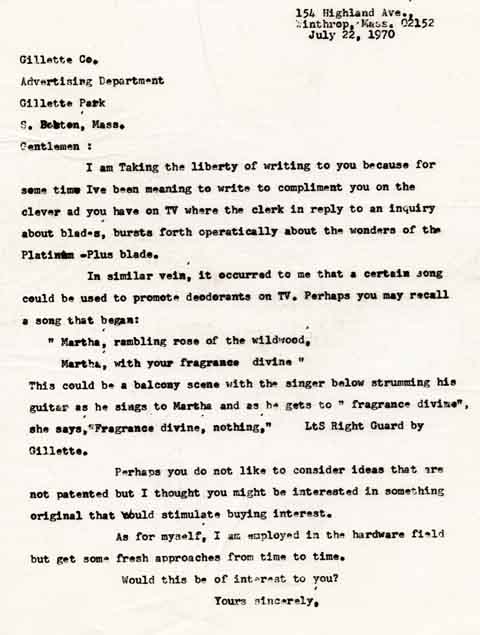

Max Gass’s correspondence reflects much of the inner workings of his wind and his values. In a letter to the Gillette Company, Max attempted to turn his flare for words into a job:

July 26, 1967

Gentlemen:

Allow me to introduce myself to you in a short summary. The following is confidential. I have charge of inventory control at Hardware Agency Co.—20 Simmons St, Boston, Mass. Prior to that, I was a partner in the Liberty Wool Stock Co., Chelsea, Mass., for eight years. I am 58 and a graduate of Boston University with degrees of L.L.I???, LLM and B.S.

I have busied myself writing in my spare time and have found a strength and knack for sayings of my own concoction. My writing to you is due to the thought that these ideas suitably imprinted on plaques might be appealing as a sales promotional idea in your Papermate line as well as some suggestions in some of your other products competing for the consumer’s dollar.

The need and demand for fresh and novel approaches may come in handy for manufacturers of the fine writing instruments and perhaps allow me to make my contribution to the growing field of knowledge. I feel that I can be of value to your organization and would like to meet you.

Sincerely yours,

Max Gass

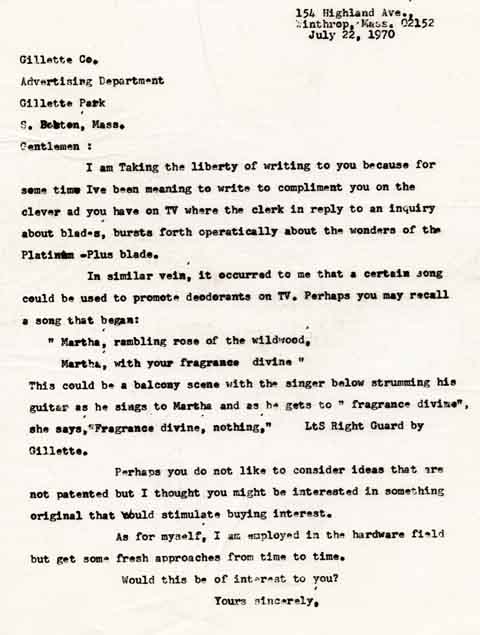

Max wrote Gillette again three years later:

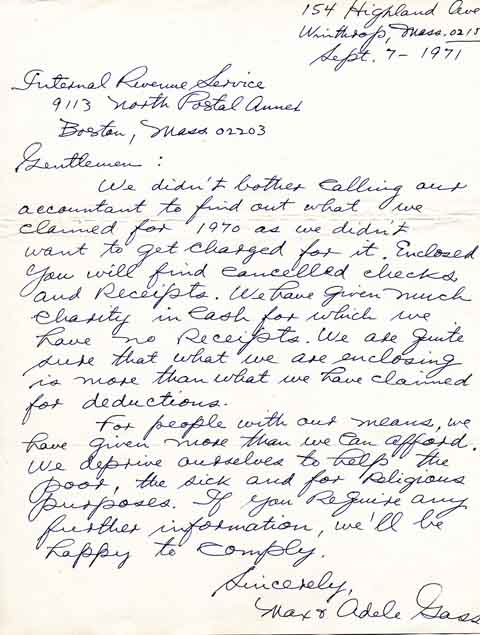

A letter to the Internal Revenue Service dated September 7, 1971, was written during a period when Max’s income was low but he and Adele continued to make generous contributions to charity.

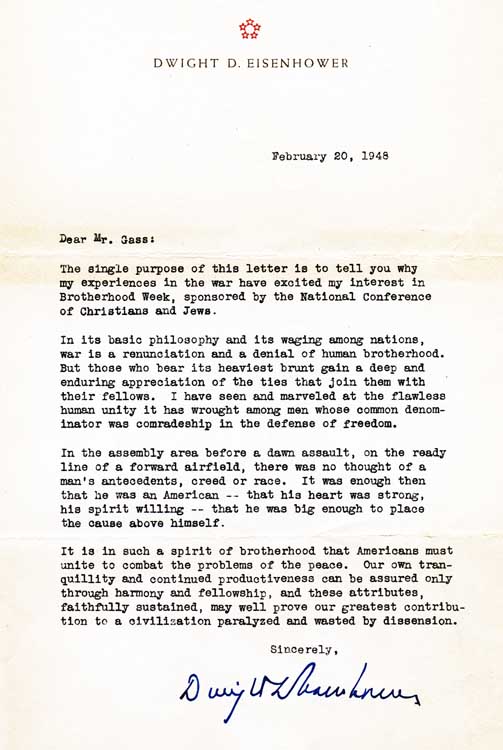

Max must have written an extraordinary letter to General Dwight D. Eisenhower because he received the following reply.

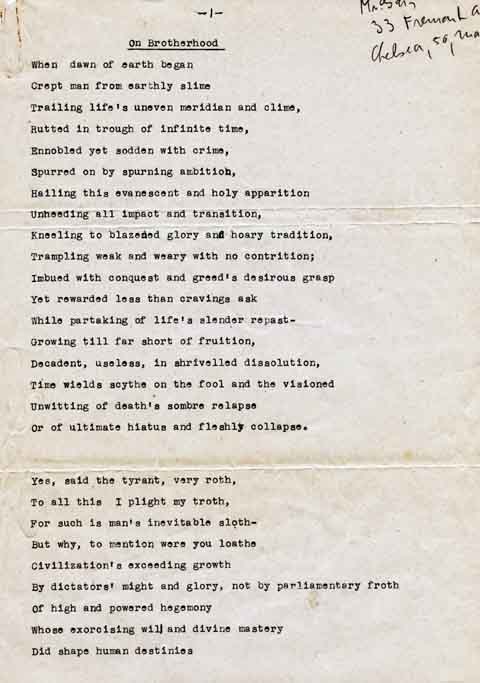

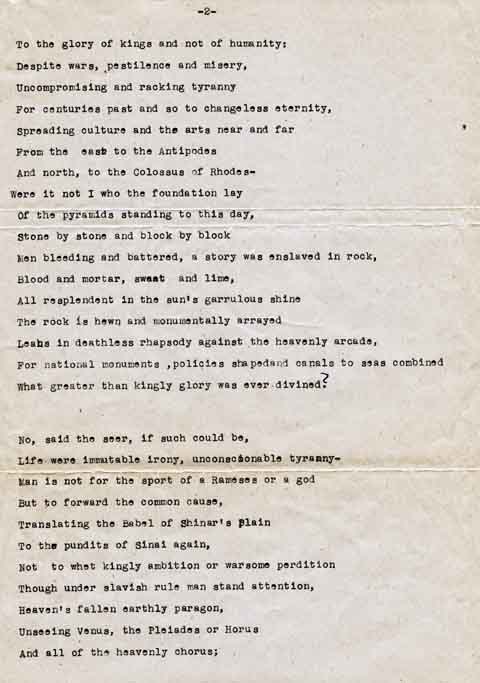

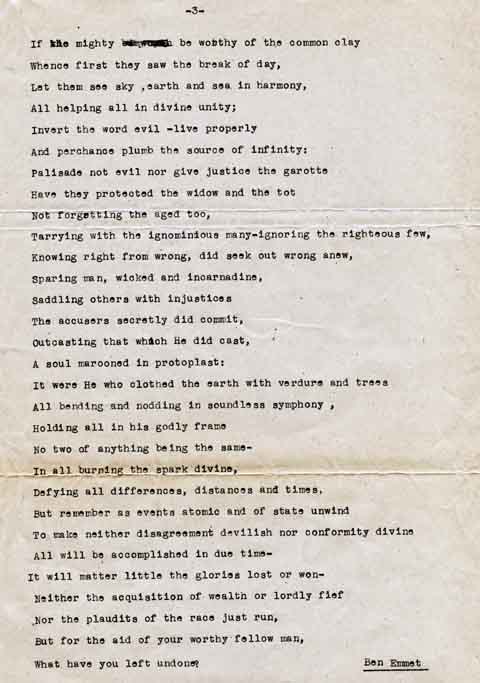

Perhaps Eisenhower was responding to this treatise on brotherhood that Max wrote under the pseudonym Ben Emmet.

Brotherhood

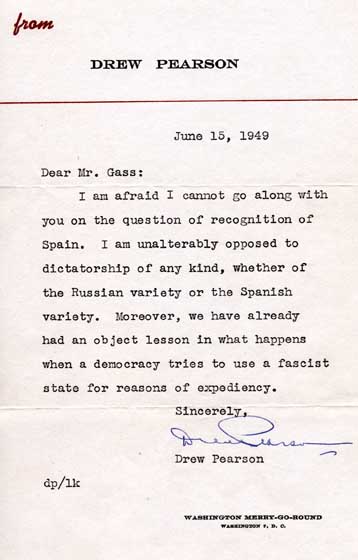

His persuasive charms however did resonate with Drew Pearson. Drew Pearson (1897-1969) was a syndicated columnist and a strong supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He was renown for exposing corrupt politicians and was vocal about his views on foreign policy. During World War II he became a radio commentator and in the early 1950s he was one of the journalists courageous enough to take a stand against Joseph McCarthy.

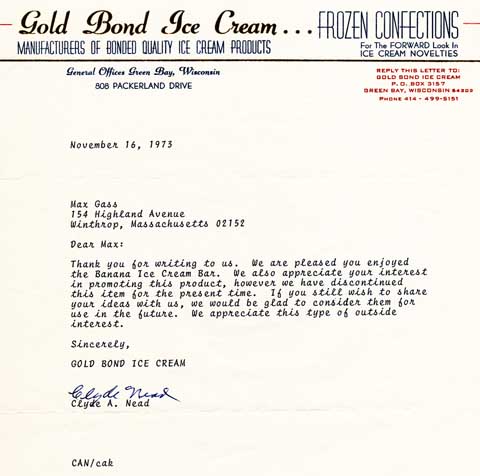

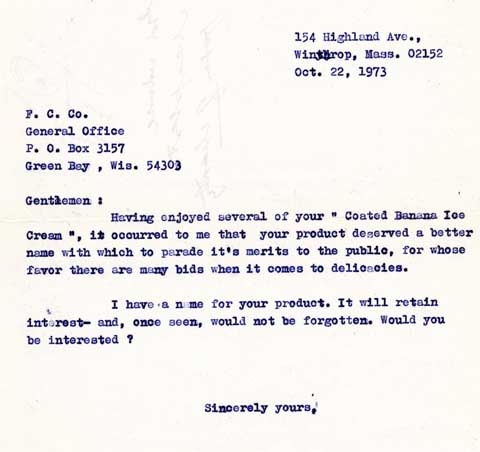

It was not beyond Max to give unsolicited advice to corporations. This letter was sent to the F.C. Company in Green Bay, Wisconsin:

Gentlemen:

Having enjoyed several of your “Coated Banana Ice Cream,” it occurred to me that your product deserved a better name with which to parade its merits to the public, for whose favor there are many bids when it comes to delicacies.

I have a name for your product. It will retain interest and once seen, would not be forgotten. Would you be interested?

Sincerely yours,

Max Gass

This letter was addressed to Richard Birnbaum, the vice-president of AC&R Advertising, Inc.

November 30, 1976

Dear Sir:

In reply to your letter of Nov. 24, concerning advertising of TAP, The Airline of Portugal, of which you are the advertising agency.

I have seen the advertisements, some in the N.Y. Times and one in the Boston Sunday Globe. They are very decorative but my approach is that despite the beautiful trips offered to Portugal and other points, more attention should be paid to the enormous travel value offered during this inflationary period when inflation has diminished the monies in the individual travel budgets that would otherwise be available for travel, particularly to Portugal, which is not so far away.

The way it could be done without diminishing what you have to offer for a Portugal trip is to start off the advertisement with the following lead line in large letters:

YOU DON’T HAVE TO BE FRUGAL

TO FLY TO PORTUGALReading the lines, Portugal has to be pronounced Port-toog-el to rhyme with frugal in order that people should remember it and look at it again. Your message should be more effective with this bit of verbal legerdemain.

Wishing TAP and yourselves every success,

Sincerely,

Max Gass

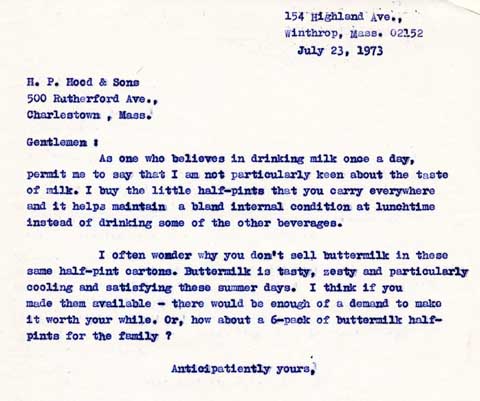

In this letter to H.P. Hood, a leading dairy in the Boston area, Max was promoting buttermilk.

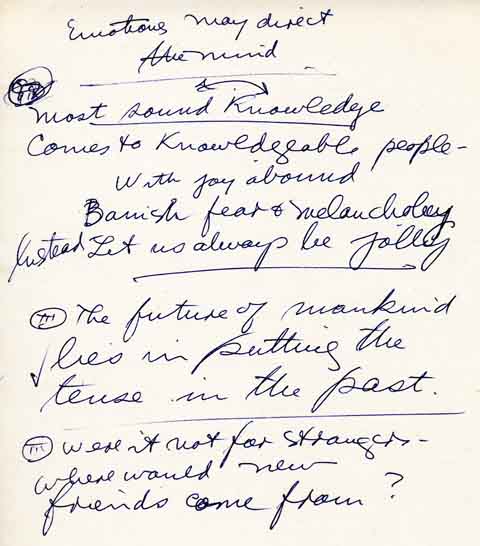

Max’s Sayings

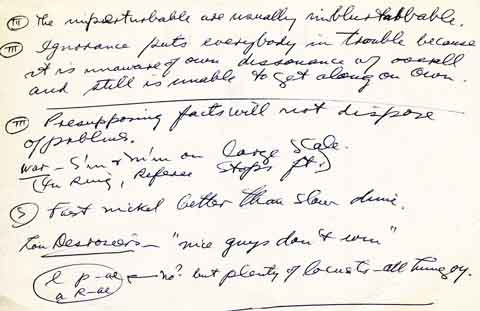

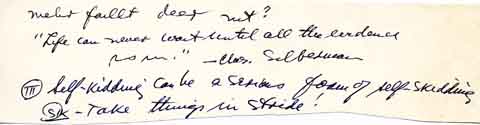

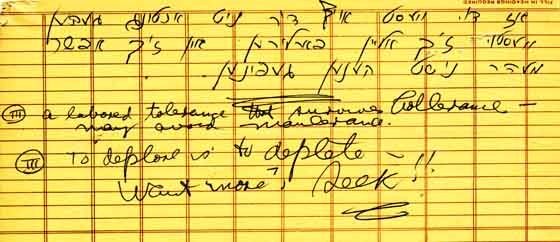

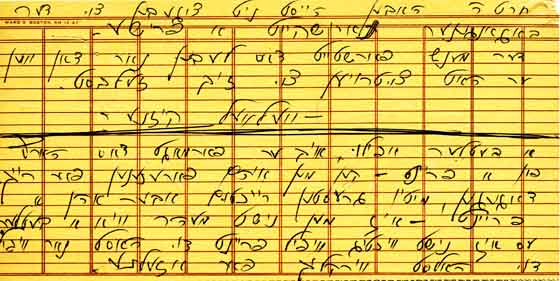

DEAREST TO MAX GASS’S HEART of all his creative endeavors were his sayings. Max loved sayings. He collected them, and he spent a lifetime writing and refining his own original sayings. Some he wrote in English, some in Yiddish, his first language. After his death his son Paul found boxes of Max Gass’s sayings, written in notebooks, on napkins and envelopes, on the margins of magazine clippings and the backs of programs. The writing was often done spontaneously at prayer services, while reading an article, talking to friends or listening to a speaker.

On a slip of paper found among a thousand others, he mused about this lifetime pursuit:

“Why do I write sayings? Merely to satisfy vanity? Possibly, but not really. For entertainment? To a degree, but not altogether. To cast light on human errors and foibles–preventing them from becoming excesses. To help make known what should be more readily known. To set down what is worthwhile. Although there is nothing new under the sun, and sayings repeated long enough sound like clichés, new meanings can be found with sufficient patience, new approaches that can cast light on the pathways of life.”

Max Gass identified his own original English sayings with the initial “M”. A series of sayings on business which he identified with the initial “S” are doubtless bits of wisdom he overheard from his father, Samuel Gass. Of the many sayings he wrote down in Hebrew script some are certainly his original work. Just as certainly some are Yiddish sayings he overheard, or are based on scriptural texts from his Judaic studies.

A small sampling of the sayings that Max collected over a lifetime

Max titled his collection at different times, Facts, Opinions and Foibles, Face, Faith and Foible, and (his favorite) Plax Du Max. He made many attempts to market his sayings—on aluminum frames, wooden plaques, greeting cards, the backs of photo prints, and with tea bags. He tried to interest Xerox, Hallmark Cards, Polaroid, Salada Foods, Celestial Seasonings, and other corporations in his sayings without success.

Read about Max Gass’s Yiddish and Hebrew Sayings

In 2004, fifteen years after Max’s death, a sampling of Max’s sayings and an analysis of his writing was published by Mikhail Khazin in The Jewish Advocate (Boston), The Yiddish Forverts (New York) and in two Russian-language magazines, Contact (Boston) and Vestnik (Baltimore).

Max’s Final Years

Neat the end of his life Max worked part-time in his son Paul’s company, Eaton Financial. These were years in which he had the opportunity to use the knowledge and wisdom accumulated over a lifetime. John Colton, Senior Vice President at Eaton, remembered Max well:

“I got to know Max when he came here. It must have been three years… He was here two or three days a week. Max was primarily an investment advisor. His responsibilities were to help manage the pension fund, the various investments that the Company had—mostly stocks and bonds.

“Instead of always focusing on the stock market where you can spend hours analyzing numbers, he had a broader perspective, which made him much more successful in looking at investments. He seemed to have a longer horizon, and sort of a larger scope than most people. That was very helpful to us because we’re a very young, very fast-growing company. And in that environment you kind of get lost. His perspective on a longer timeframe gave us a tremendous sense of balance.

“I saw the results. The pension plans and the profit-sharing plans did very well in those years. He really contributed while he was here. It was good for both sides.

“Every time something happened—nuclear disaster, the stock market going down, rising interest rates—he always seemed to be able to look beyond that sort of short-term negative. That’s very comforting. I think that came from inside. This was a company which was doubling in size every year, which had gone from thirty employees to—well we’re four hundred employees today—in less than four years. So in this explosion of growth, and people coming and going, he seemed to have a very calm approach to things. And he always did it with a smile.

“He was a fascinating man. For someone who essentially had the job of analyzing investments—which meant he didn’t work with others, because he was the only one who did it here—he still got to know everybody. He took a genuine interest in the people that were here. To him it didn’t make any difference what you did. You were an Eaton employee and it didn’t make any difference whether you were a Senior Vice President or a part-time clerical.

“We were all extremely fond of him too. He had a very warm quality. Genuine interest in people and a way of always appearing to be happy and pleased with what was going on with both the people as well as the company.

“I was at the time the oldest employee. I would have been fifty-two or fifty-three. The average employee was probably just twenty-seven or twenty-eight. So he was the only really mature person here. And he really enjoyed the younger people. Unlike a lot of older people he never criticized, never, whether it was short skirts or loud music or whatever was going on. Sometimes you’d find him in deep conversation with one of the younger people here. Just interested in what they were doing, what they were thinking.

“In all the times that we talked he never talked about the past. He always talked about the future. But you never could talk to him about something like Is the stock market going to go up or down? He wanted to talk about why, and what that means today as you look out into the future. Whether it goes up or down really was not as important as the way things happen.

“He was always humorous. If you think of a word picture of him you have to include the word smile. And you’d always see people smiling around him.”

Max Gass in his later years

DOROTHY VINE, VICE-PRESIDENT at Eaton during the time Max worked there also remembered him as a very thoughtful man:

“I think he had a way to relate day-to-day things to the bigger picture. He was very oriented towards values. He didn’t look like a businessman. To me he looked more like a professor. There’s a certain kind of authoritativeness that comes from age. I had a lot of respect for him as far as his mind went. He was a real smart man. He was always interested in sharing his ideas and his thoughts about really any subject.

“Max loved to get into conversations. He didn’t push himself on people, but if you showed any interest at all, ‘Let’s talk.’ He seemed to really enjoy just being connected with people. He wasn’t one to bury himself in his office.

“I think Max really was concerned about humanity as a whole. And it was almost like we should be able to do something about it. He may have been a person who would have been happier living in a different period, in the old type culture where scholarship and family were honored and religious values were dominant. He carried that around with him, the value system he inherited. He tried very hard to understand the time he lived in.”

Judy Gass, Paul’s first wife and the only daughter-in-law Max got to know, had warm memories of those years:

“When he came to work in the business in the later years, he and I came to know each other very well. He used to come in and sit in my office and chat. And so I had a chance to understand his dreams, where he had come from and where he had wished to be.

“I think the years that he worked at Eaton were probably his happiest because he wasn’t his father’s son, and he wasn’t his wife’s husband. He was Max. And the people in the business loved him. He would get his tea with his lunch and he would have his yarmulke on his head and he was hard of hearing, so he talked loud and everybody else talked loud. So you would hear these conversations, and people really liked him.

“He would float into my office and sit there and we’d have a kibbitz and it was nice. He loved to tell puns. You knew that he appreciated the turn of a word. He smiled and you could see that twinkle in his eye, if you were on the same wavelength with him and you picked it up. He was always willing to give people little Talmudic anecdotes and interpretations.

“And when he’d come to the holiday party we’d have each year—he never went to restaurants—he felt self conscious about going out and putting on the yarmulke, that people were going to look at him. But when he got his invitation to the Eaton party, he came, no question. And people came over and they introduced their spouses, ‘This is Max.’ At the Christmas party he wore his yarmulke and he felt very comfortable.

Max mingling comfortably at a social event

“I really worried about him when he was coming to work. He lived in Winthrop and he used to take route 9 to Framingham, the old road, because he did not want to drive fast.

“One day I was sitting in the office, Paul was out of town, and people came running in, ‘Judy, Judy, Max just fell down the front stairs.’ His glasses were bifocals and I guess he looked down and everything gets very out of focus. Anyway, he tripped and flew down those steep marble stairs and banged into the glass door at the bottom. So we called 911, and the fire department sent their ambulance.

“I took a look at him, and he didn’t have a bruise, nothing. He wasn’t hurt; it was amazing. So they put him on the stretcher and told him to lie still, and he says to me, ‘I hope there aren’t any photographers around; this won’t be a good thing for the company’s image.’ He was worried about the bad publicity for the company, not about himself!”

Paul Gass felt that Max had a premonition of his own death. Paul remembered walking with his father to pick up tuxedos for Max and Adele’s fiftieth anniversary party. Max had difficulty walking and was thinking out loud about what was happening to his body. Suddenly he stopped and said, Oh, I understand. When they came to the car he came over to hug Paul, unusually demonstrative for him to do out on the street. At the party that night during the filming of a video, Max made a speech on camera, holding onto the floor as if he wanted to leave some final thoughts to his family.

His granddaughter Leslie remembered the last time she saw him at the party:

“He was looking everywhere for me, and then I found him, and he said this long goodbye and gave me a kiss. I had such a warm feeling from him that night. It’s strange—sometimes I think he knew he was going to die.”

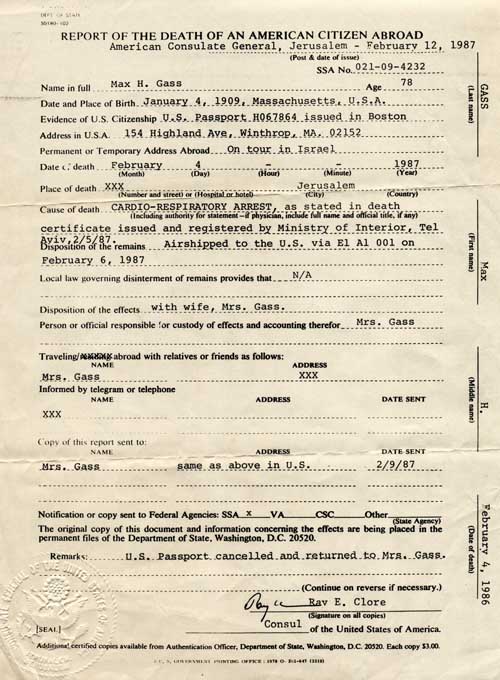

In 1987, soon after their fiftieth wedding anniversary, Max traveled to Israel with Adele. While in a Jerusalem hotel he died suddenly of a heart attack on a Friday while preparing for dinner.

Official report of Max’s death issued by the U.S. Consulate in Jerusalem

Lisa and her sister Leslie remembered Max as an affectionate grandfather, gentle and kind. He loved to dance with his small granddaughters at celebrations, Bar Mitzvahs. They would stand on his feet and he would dance. They used to play Mashie-Pashie, a traditional Yiddish card game, with him for hours.

Leslie recalled:

“He taught me to play chess when I was eight and now I have his chess board and pieces. He was kind of solitary when we were young—he’d go upstairs a lot to read and pray. He became more liberal as he got older. I remember after he died that we found all these liberal books in his library and it was a big surprise—things I wouldn’t think he would be reading.”

Lisa recalled:

He always called me Tovah, which was my Hebrew name. I told him I hated it, but he would say, But your name is Tovah, you are Tovah. It was important to him that I identify with my Jewish heritage.

Eulogy for Max Gass

AT THE FUNERAL FOR MAX GASS, his son Paul delivered a eulogy that best conveys the essence of the man:

“Shortly after he celebrated his fiftieth wedding anniversary and seventy-eighth birthday with his friends and family, my father and mother traveled to Israel. There on February 4, 1987, my father passed away.

“All his life, three times a day, my father faced east to Jerusalem to pray. Last week his soul passed on at the source of his prayers. He couldn’t have been any happier than he was in Israel with my mother, whom he loved with all his heart and soul. He worked up to the day before he departed for Israel. There was no illness. There was no pain. When his time came, G-d truly blessed him.

“My father tried his whole life to be a good person. He was a man of conviction, proud of being Jewish, religious and observant, respectful and dedicated to his faith. He was pure of heart and held the highest moral and ethical standards; his values were simple values of Good versus Evil—no half truths or white lies. A scholar, always learning and relearning, he was a writer, philosopher and poet. My father was honest and sincere, gentle and humble. He could not hurt a living thing—not a bug, a branch, a flower, anything.

“He loved his family and religion with a passion, was devoted to his mother, father, and sisters, cherished all of his nieces and nephews, and was extremely proud of his grand-children, Lisa and Leslie. His love for my mother was total.

“His ‘declining years’ were some of his best. Comfortable with himself, with business and religion not in conflict, he was at ease having lunch in the office or at a company party wearing a yarmulke. He seemed to enjoy the younger generation—people in their twenties at the office—even better than those in their sixties, seventies, and eighties at a synagogue, and was able to communicate with everyone on a wide range of subjects. When he arrived at work everyone talked a little louder so he could hear. He had a dry sense of humor and loved to make puns and plays on words.

“At the office when he was concerned about a pension or profit-sharing plan investment, he would demand attention; however, when he fell down the office stairs he wanted no attention for fear the company would get bad publicity.

“He was able to be religious, communicate with all generations, be productive and helpful, and not compromise his values. He lived his last years as he wanted to live them.

“On his desk there was a quotation—one of many quotations: Learn from life and correct your mistakes in living. I believe he worked very hard to do that.

“We all had good feelings for my father. He really succeeded in being a good man. He really succeeded in being a beautiful man. He said at his seventy-eighth birthday party a few short weeks ago: You cannot keep the candles burning forever. Do as much good as you can to keep the light burning. The world truly needs more light”.

Perhaps Adele Gass’s sister Betty Berkowitz encapsulated Max’s life the best:

“I remember Max Gass as somebody you could sit and talk with for hours, somebody who cared about humanity. He was highly educated, very well spoken. To me he seemed a fountain of knowledge. If it were up to him everybody in the world would have been good, people would do the right thing.”

In the wake of Max’s passing, Paul began the Gass Family History project as a means of honoring the memory of his father.