Refuge in Canada

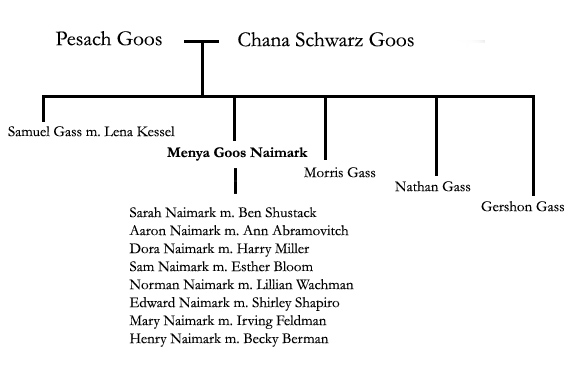

MENYA GOOS, THE SECOND OLDEST of Pesach and Chana Goos’s children, had a more difficult life than her brothers. Menya was born in Turiysk, Russia, on January 6, 1883, and when she was a young woman, she entered into an arranged marriage with Jacob (Yankel) Naimark. They lived in Menya’s childhood home, the house that had belonged to Pesach Goos. Although Menya and Jacob had 10 children, the marriage was not a happy one.

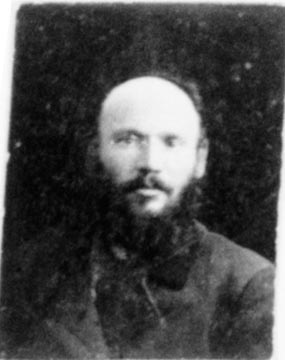

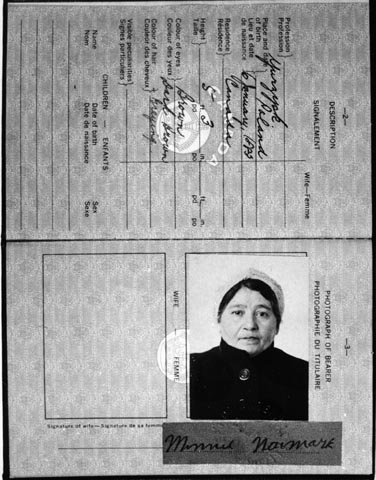

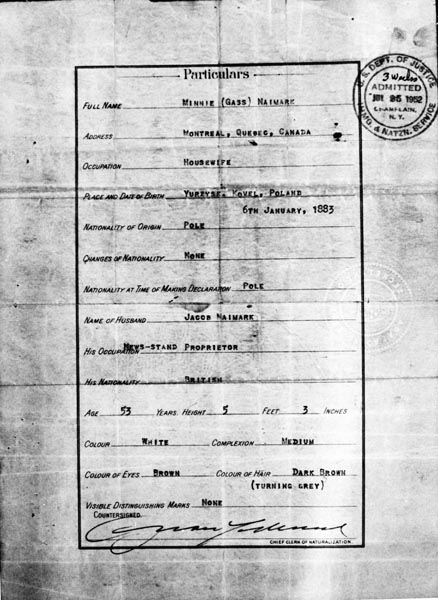

Minnie Goos Naimark (1883-1965) and Jacob Naimark (1880-1957)

All of the Naimark children were born in Turiysk. The oldest child, a son, died in Turiysk at age 16, and another child died at birth. Their names have been forgotten. Menya and Jacob brought their eight surviving children with them to Montreal, Canada, in March 1927. They included:

Sarah Naimark Shustack (1907-1983)

Dora (Dvorah) Naimark Miller (1909-1981)

Aaron Naimark (1910-1987)

Sam (Shloime) Naimark (Born: 1913)

Norman (Nute) Naimark (1914-1987)

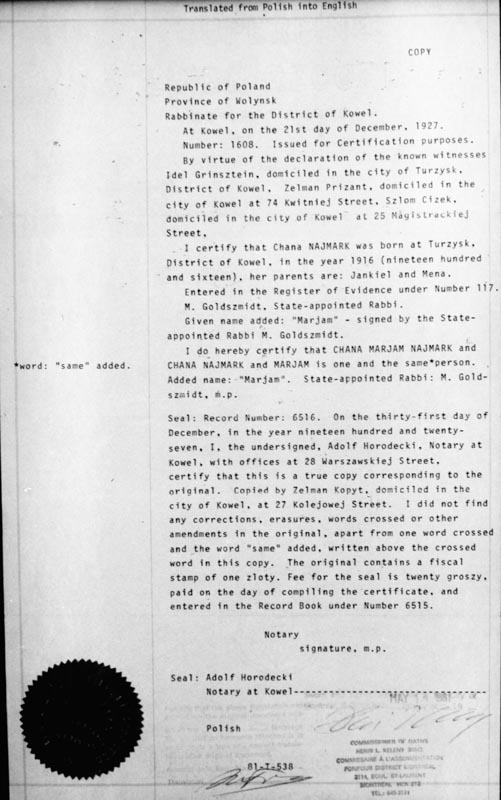

Mary (Chana Miriam) Naimark Feldman (Born: 1916)

Edward (Isick) Naimark (Born: 1918)

Henry (Huna) Naimark (Born: 1920)

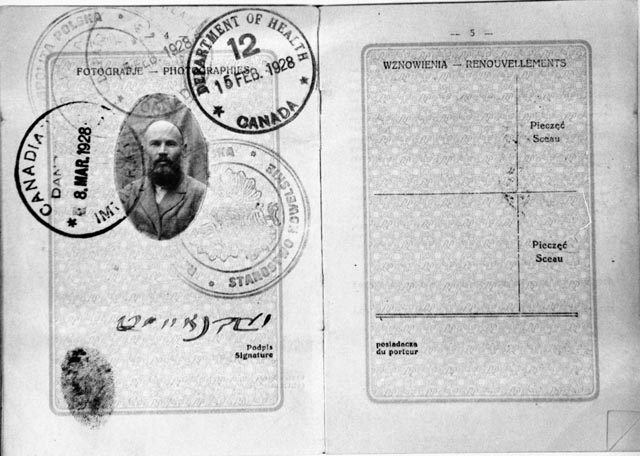

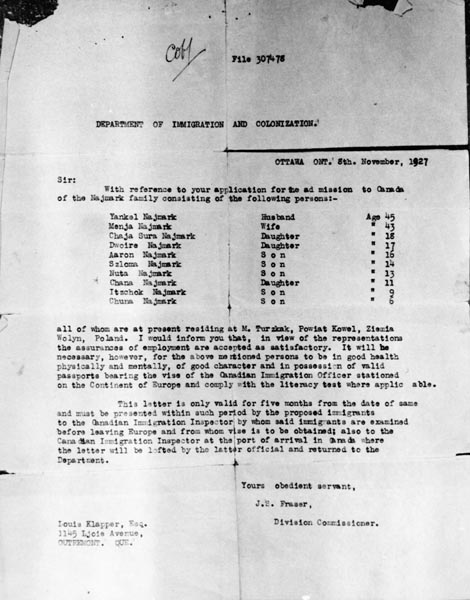

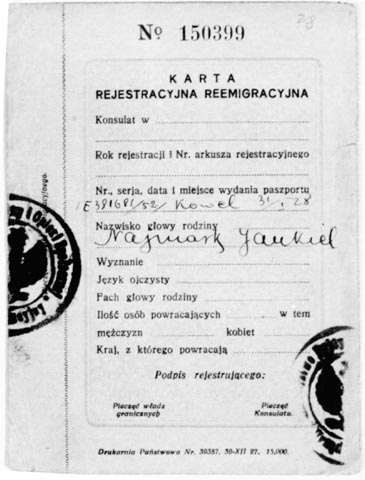

Canadian document enabling the Naimark family to immigrate to Canada

After the first of the children were born, Jacob immigrated to the United States. He probably went between the births of Aaron and Sam. Jacob visited Chelsea, Massachusetts, where his brother-in-law, Samuel Gass, had already established himself in the rag recycling business. However, Jacob decided to set down roots in New York City because friends from Turiysk—landsmen—had settled there. Jacob lived in New York for two years, but lacking a trade and an education he found it too difficult to succeed, and so he returned to his family in Russia.

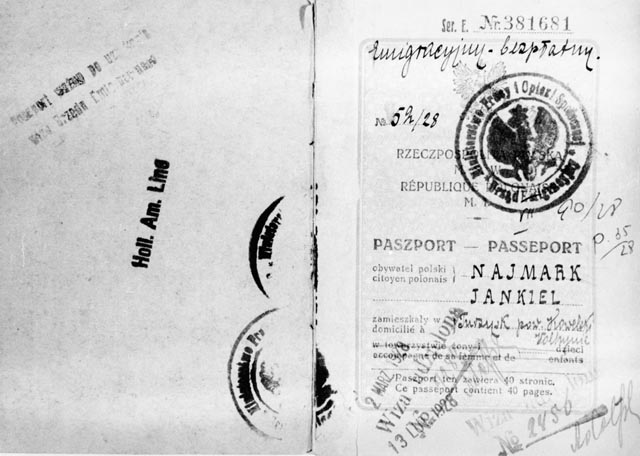

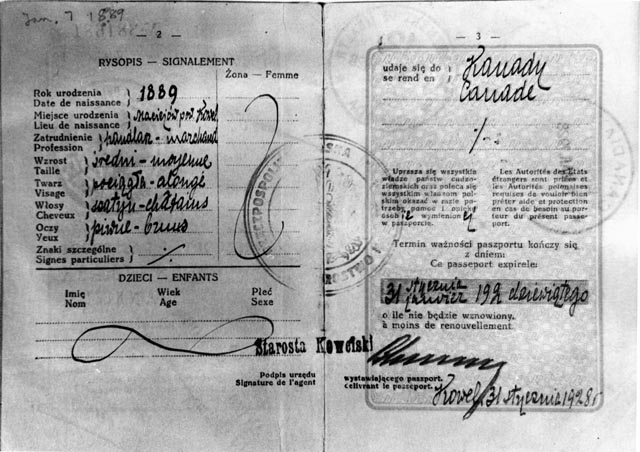

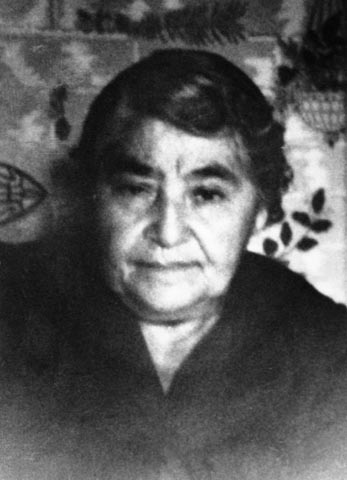

Jacob Naimark’s early passport photos and passports from the old country

Menya’s son Sam Naimark remembered their life in Turiysk:

“I grew up in a small village with about 150 Jewish families. It was on a river in the Ukraine, near the Polish-Russian border. The town was one-third Jewish, one third-Polish and one-third Ukrainian. The Ukrainians hated the Poles, the Poles hated the Ukrainians, and both of them hated the Jews. I have a scar on my head from an unprovoked attack in Turiysk. A boy—either Polish or Ukrainian—threw a stone and struck me in the head. The gash required stitches but there was no doctor available. Polacks in gangs would sneak behind Jewish men and cut off their beards with knives. This happened to my father once and after that he kept off the beard.

“My father worked hard at different jobs. For a while he was in the wool business. He walked miles and miles to Warsaw to collect wool. He would be gone three or four days. Then he returned home and dyed the wool. He sold it on Tuesdays—market day. People came to Turiysk from all the small villages around it to sell and buy goods. My father was able to sell the wool but he could not make a living. My mother’s brothers sent her money from America. Jacob was not lazy, and he was resentful that he had to depend on his brothers-in-law for support.

“The Ukraine is a region for growing grain. At first in Turiysk there were only windmills to grind the grain. Then one man built a water mill on the river. He knew the business, but he was uneducated and old, so he needed a smart Jew to run it. My father managed the mill for him, and we all worked at the mill. The grain in fifty-pound sacks would be brought in to be weighed. My job was to record the weight and figure out the price for grinding it. Then the sacks were carried upstairs and the grain was ground into flour.

“In Turiysk, my mother had a lot of friends. She was a very likable woman and good to the children. She worked very hard but always employed a Ukrainian woman who lived with us. As cramped as we were in our small house we had to find the woman a place to sleep. She helped my mother with the housework.

“In back of the house we had about three acres of land. Every growing season this woman, my mother, and the oldest children would help to cultivate the land to grow all kinds of vegetables—lots of vegetables, which would last us practically from one growing season to another.”

Turiysk street scene

In the small town of Turiysk all the Jews kept an eye on each other. This not-so-subtle pressure fostered the keeping of tradition. Each day, there were morning, afternoon, and evening services, which all the males of the community attended. According to Sam:

“Menya was an observant Jew. She lit Sabbath candles every week and observed the other traditions. Each year before Rosh Hashanah, she went to the graveyard and visited her father’s grave. During the shiva [mourning] period after the death of a close relative, Menya covered the mirror in black. She always washed her hands after returning from a cemetery.

Sam Naimark recalled how Turiysk changed with the times:

“During World War I, Turiysk was occupied by Germans. The soldiers used to steal food from the barracks and gave it to the Jews but not to the Poles or Ukrainians.

“After the war, Turiysk came under Polish rule. My mother insisted on leaving because of us children—she didn’t want her sons to grow up and serve in the Polish army. At seventeen, boys were called up. If you were a sixteen-year-old male, you couldn’t even leave the country. When Aaron was sixteen my parents paid some lawyers a lot of money to change the dates of our birth certificates and make all the boys appear to be a year younger. I know I was born in 1912, but on all my papers my birth date is 1913.[1] Once Aaron appeared to be fifteen years, he was allowed to emigrate.

“My mother had always wanted to join her brothers in Chelsea because of the pogroms in Russia and Poland. In 1927, Jacob finally was persuaded. He listened to my sisters, Sara and Devorah [Dora]. Immigration into the United States was then on a quota basis, and it would have taken another ten or twenty years before our family could obtain entry. We were able instead to get papers into Canada. Menya’s brothers all chipped in to pay for our passage and we moved to Montreal, it being the Canadian city closest to Boston. Menya brought from Europe her samovar, two silver candlesticks, and a silver Kiddish cup.

“We came over on the Vollendam, a freighter with few accommodations for passengers. Every one of us was seasick except for Aaron. He had a job attending to everybody else. Nobody could sleep and nobody could eat. Most of the time we stayed below deck except to throw up.”

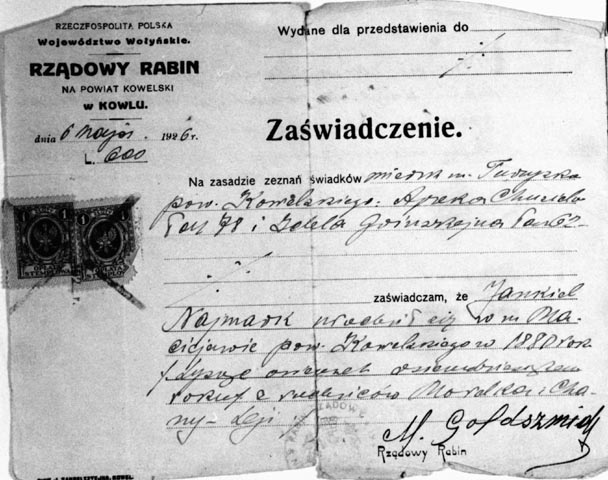

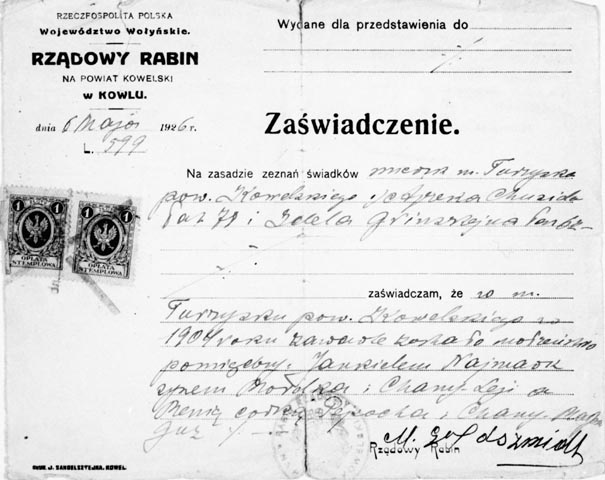

A translation of a notarized Polish document attesting to Chana Marjam (Miriam) Naimark’s birth in Turiysk in 1916

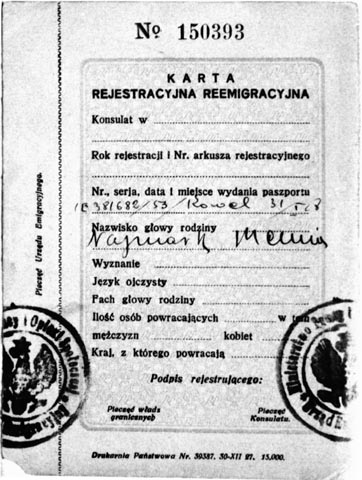

Menya and Jacob used these passports to leave Poland.

Menya’s brother Morris Gass and his wife Sarah came to Montreal and greeted the Naimarks when they arrived. The first night, Sarah found a home where all ten Naimarks could stay. Within a day or two, she had rented an apartment for them and enrolled the younger ones in school. She went shopping as everybody needed clothing. She also gave all the family members their English names.

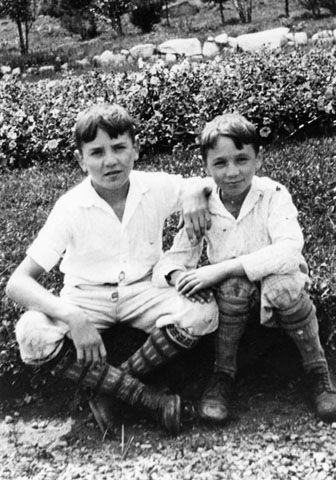

Eddie and Henry Naimark, the youngest sons of Menya and Jacob, were able to get an education when the family moved to Canada. The oldest siblings had to work.

In Montreal, with help from his brothers-in-law in Massachusetts, Jacob purchased three newspaper stands, and he and his two oldest sons, Aaron and Sam, went into business. The younger children attended school. During the years that followed Jacob worked at various jobs. Lillian Naimark, Norman’s wife, recalls:

“Jacob didn’t know the ways here. The boys didn’t want to sell newspapers anymore and went on to other things. For a while Jacob went into the brush business. And before that he was in Dependable Slippers. But he had been a farmer in Europe, he ran a mill, he wasn’t a businessman. He didn’t make a big success of any of the businesses he went into here.”

Jacob attended shul regularly. He paid for one seat for himself but not for his sons so they didn’t attend the high holidays when the shul was filled to capacity. As a reaction, when his youngest son Henry went to shul as an adult, he always took seats for his own children.

View of Montreal from the Church of Notre Dame

Credit: ©1900. Detroit Publishing Company. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-D4-15494]

Dominion Square, Montreal

Credit: ©1900. Detroit Publishing Company. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-D4-12496]

Place Viger Hotel and Station, Montreal

Credit: ©1900. Detroit Publishing Company. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-D4-12499]

Montreal city hall

Credit: ©1900. Detroit Publishing Company. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-D4-12497]

An ice castle built for Montreal’s Midwinter Carnival, 1909

Credit: ©1909. Keystone View Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-96850]

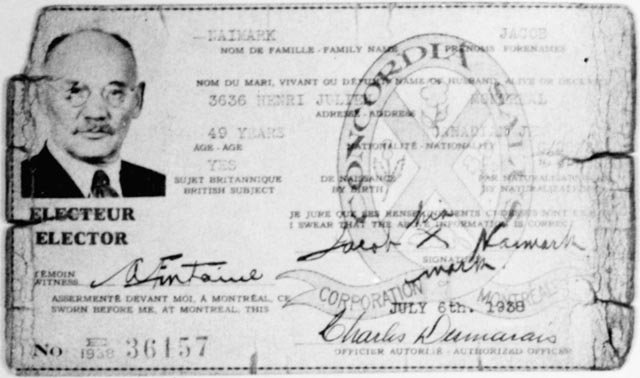

Jacob Naimark at 40. Is this identity document Jacob’s Canadian voter registration card?

Menya is remembered as a lovely woman, very good-natured and intelligent. She was very motivated to learn to speak and read English, and she anglicized her name, changing it to Minnie. She took English lessons in a Jesuit Church and paid her children to speak English to her. She even taught herself to write.

Despite her interest in the modern world, Menya still clung to some superstitions from the shtetl. She believed 13 was an unlucky number and she tied red ribbons on cribs to keep away the evil eye. If someone would compliment a beautiful or smart child, Menya would say (in Yiddish), Three women sitting on a stone wherever it came from it should go back. Pu-pu-pu.

MENYA’S SON SAM REMEMBERS Menya as being very good to the children:

“She had a heart. If a kid hurt himself and started crying, she would cry. But not my father, he was strict with everybody.”

Menya maintained close ties to her three brothers and occasional visits took place between the Massachusetts and Montreal families. Whenever Menya went to Chelsea, she always came back with a permanent and outfitted with new clothes from top to bottom. Whenever her brothers visited Menya in Montreal they always came with a suitcase full of women’s shoes in all sizes with the bottoms scraped to make them look like they were used. [This was probably a ploy to avoid paying duty on the shoes at the Canadian border.]

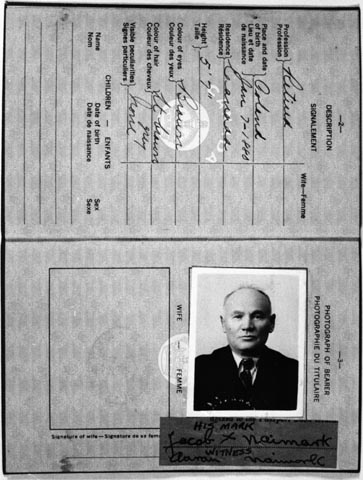

Jacob and Menya’s Canadian passports

U.S. document allowing Menya to visit in the United States

The most frequent visitors to Montreal were Morris and Sarah Gass with their children, and Adele Gass, Max’s wife. Samuel Gass visited Menya once or twice a year and stayed as long as his supply of Camel cigarettes and instant coffee lasted. When word came that Samuel Gass had died, Menya dropped to the ground and knocked her head against the floor.

Jacob and Menya Naimark were not a happy couple.

Each summer, the Naimarks spent three weeks in Chelsea, one week with each brother’s family. These were delightful, happy times. The Naimark children would be taken on outings with their cousins. One Sunday each year there was a grand picnic, which included all the brothers, their wives and children, and the complete extended family. Louis Gass, a more distant relative who was very close to Sam Gass, organized this event year after year. Despite all this togetherness, the Naimark children never got to know their uncles intimately.

The Naimarks also had extended family in America on their paternal side. Jacob’s brother, who went by the surname, Newmark, lived in Brooklyn, New York. Jacob left another brother behind in Turiysk—Surik (Israel) Naimark—who perished in the Holocaust with his family. This is a fate that the Naimarks would have shared if they had not immigrated. None of the Jews who were living in Turiysk at the start of the Holocaust survived it. The Naimarks knew they owed their lives to the Gass brothers.

The marriage of Jacob and Menya, the product of a matchmaker, was not successful. Jacob communicated poorly with his wife and children. Menya never complained, but in 1948, after the children were grown and married with children of their own, Menya left her husband.

Their grandson Arnold Feldman, the son of Mary Naimark and Irving Feldman, remembered them both after the separation:

“Jacob appeared to be a very old man, possibly because he was bald and religious, always either coming from shul or going to. I remember visiting on Sundays, or perhaps after Bar Mitzvah lessons, drinking tea from a glass. It was a very small apartment and we were a lot of grandchildren.

“I remember my grandmother more vividly. She spoke English very well and she taught me a Hebrew prayer to say before I went to bed at night. She was a very kind person. I visited her at Maimonides, which is a [nursing] home, after her heart attack, and she told me she had a good life. It had been a hard life but she was happy.

“She told me a story about when she was much younger. She was in bed, quite sick, and I guess she had high fever, and she said she had a vision she was dying. God came to her and said, What are you doing dying? You have eight children, you’re not ready. And she got better.”

Jacob Naimark passed away in 1957, and Menya in 1965.

Menya (Menya) Naimark

Menya and Jacob’s children all succeeded in the “new world.” In 1932, at the age of eighteen their second son Sam Naimark joined the first American/Canadian group to go to Palestine as kibbutzim. In Palestine, he met his wife Esther Bloom. They returned to Canada with their baby daughter in 1937 during the height of the Depression. From Montreal they made their way to New York City where Esther’s brother owned a bakery. He gave Sam a job driving the delivery truck, and Esther worked in the bakery. They eventually ended up in the liquor business in California.

Passport covers

Read about Sam and Esther’s experiences in Palestine

SAM NAIMARK RECALLED THE EVENTUAL SUCCESS of his brothers and sisters:

“In 1934, Aaron married Ann Abramovitch, a native-born Canadian. He went into the import/export business. He would make about three or four trips a year to Japan and buy a lot of the stuff that you find in five and ten cent stores. He had a big place at that time. The other boys, Norman, Eddie, and Henry, worked for Aaron as salesmen. He had customers—retail stores—practically all over Canada until World War II broke out.

Back row, left to right: Aaron & Ann Naimark with their children Mona and Allan standing in front of them (Edward wasn’t born yet); Esther & Sam Naimark with their children Elaine and Dena, 1943 or 1944

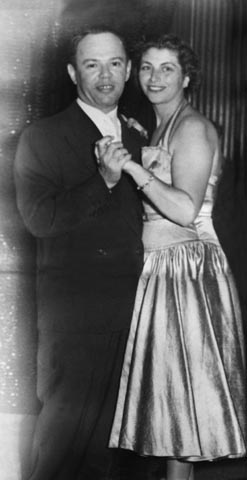

Ann Naimark dancing with Aaron

“The two youngest brothers, Eddie and Henry were taken into the army. A few years after the war was over, they went into the same kind of business as Aaron and began to compete with him for his customers. For the first couple of months there was some friction, but then Aaron didn’t mind. In 1950, he sold his inventory to Eddie and Henry, and went into the lingerie business. Eddie married Shirley Shapiro, and Henry married Becky Berman in 1944.

Wedding photo of Edward & Shirley Naimark, November 1944

“Aaron made a big success with his company, Supreme Lace. He built the Naimark Building in Montreal… Henry and Eddie bought the building from him, just before he died. [Aaron died in 1987.] Now Henry owns it with his two sons. Henry’s boys run the business today.

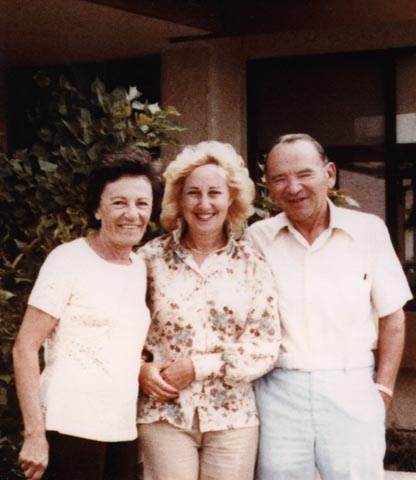

left to right: Henry, Becky, Shirley, and Eddie Naimark

“Sarah was a self-made person. All her life she worked in the needle trade, the factories. Her husband, Ben Shustack, was in the fur business. They made fur coats. Dora also worked in a dress factory until she and her husband Harry Miller went into the dry cleaning business.

left to right: Eddie & Shirley Naimark, Ben & Sarah Shustack, Irving & Mary Feldman, Pat Gass, Anna Gass, Adele & Max Gass. The Gasses were first cousins to the Naimarks, the children of Menya’s brother, Sam.

“Norman married Lillian Wachman and got into his father-in-law’s business, Atlantic Paper Box. He was a salesman. Norman passed away in 1987.”

Lillian and Norm Naimark

Norman’s wife, Lillian Naimark, shared her recollections of Norman and his siblings:

“Norman and I met in the summertime and had a wonderful summer romance. I was very happy in my marriage. We weren’t millionaires, but we were in love and happy with what we had. Our children turned out well, so I have no complaints.

“Mary married Irving Feldman in October 1939. Mary never worked. Her husband Irving was in dry cleaning and cloth dyeing. When they first got married, Mary and Irving lived in her parents’ apartment in a little back room, and Norman and I lived with my parents. Mary and I went looking for apartments but neither of us could afford very much. We decided to rent a two-bedroom apartment together. Each couple had their own room. We lived together for about a year and a half, until we started thinking of a family.”

The Naimark clan at a happy occasion: left to right: Irving and Mary Feldman, Ed and Shirley Naimark, Harry and Dora Miller, Aaron and Ann Naimark, Henry and Becky Naimark

Esther and Sam Naimark with one of their daughter

Of the eight Naimark siblings only Sarah Shustack and Dora Miller had no children. Sarah’s husband Ben passed away in 1955. After his death, Sarah married Ruby Robinbach. Dora died in 1981 and Sarah died two years later.

Important note about the quotes used in this chapter:

The quotes that appear here were edited by Eleanor O’Bryon, the first writer for the Paul Gass Family History project, and they differ from the transcripts of the original interviews with the Naimarks. However, the quotes correspond directly to the ones in a report labeled “edited transcripts.” It is not known whether the Naimarks approved the edited transcripts. See the original transcripts: