NOVOGRAD VOLYNSK

AFTER TWO NIGHTS IN KIEV, Vitaly drove us to Novograd Volynsk. Our photographer and his son accompanied us in a separate car. The drive itself was an experience. Ukraine lacks the interstate highway system that we take for granted In America. The main roads that connect major cities would be considered side roads in the United States. On our drive we shared the road with an assortment of old, dilapidated vehicles, a few newer ones, horse-drawn wagons, bicyclists, and people on horseback.

Cars and horse-drawn wagons sharing the road are a typical sight in rural Ukraine.

Photos credit: Miriam Weiner of Routes to Roots

Because of its close proximity to the Polish border, Novograd Volynsk is a military town with a large garrison. Prior to the Holocaust, 50 to 60 percent of the population was Jewish. Now only 5 percent is Jewish—800 people have acknowledged their Jewishness. Perhaps two to three times this number are Jewish but they are afraid to declare it. Most of the Jews in Novograd Volynsk came from other regions of the former Soviet Union, and are not descendents of the pre-Holocaust Jewish population.

In Novograd Volynsk we stayed at what was billed as a “four-star hotel.” It contained the best accommodation and restaurant in the region. Miriam Weiner had warned us ahead of time to bring our own pillowcases, towels, soap, and toilet paper. We were glad that we had heeded her warning.

Our accommodations on the fourth floor were called the “Presidential Suite”, which consisted of two rooms and a bathroom with ancient plumbing. Unfortunately, the water pressure in the town was so low that water reached us as a trickle. This was good enough for a slow sponge bath but insufficient for a shower.

Best hotel and restaurant in Novograd Volynsk

Photo credit: Miriam Weiner of Routes to Roots

One of the bedrooms contained two single beds, which were old and uncomfortable. The other room had a futon that didn’t unfold completely. Not unexpectedly, the rooms lacked TV and radio, but they did have roaches. The hotel’s restaurant served a limited selection of food, most which was fat laden and almost inedible to the American palate.

Vitaly and Miriam had prearranged meetings with the town officials for us wherever we went and we were treated like visiting dignitaries. We always brought gifts such as pens, rulers, staplers, and scotch tape, and in turn the officials gave us souvenirs, such as postcards of the town (not easy to find because they aren’t available for purchase), booklets containing town histories, town maps with Jewish sites marked, even a vase.

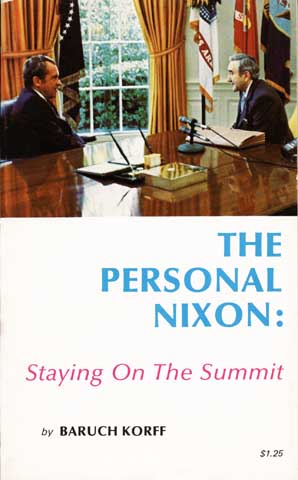

In 1974, Baruch had published a paperback book, The Personal Nixon: Staying on the Summit, which contained Nixon’s final extensive interview as president. A photo of Baruch interviewing President Richard M. Nixon in the Oval Office emblazoned the front cover. During our travels Baruch carried around a supply of these books. When we encountered someone who had been especially cordial to us or could smooth the way, Baruch would autograph a copy of the book and give it to the person. Nixon had been very popular in Russia, so the books were a big hit.

Baruch’s book

In Novograd Volynsk the mayor, Vladimir Ivanovich Zagrevy, showed up the first day to greet us but that was the extent of our interaction with him. The assistant mayor, Leonty Nikolayevich, was assigned to us to be certain that we were 100 percent satisfied with our treatment.

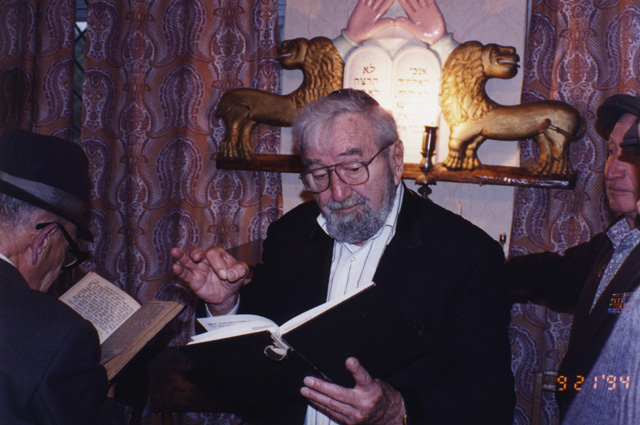

Baruch showing a book to the mayor of Novograd Volynsk, Vladimir Ivanovich Zagrevy. The middle-aged woman looking on is in charge of providing human services to the elderly Jews in the community.

Leonty Nikolayevich, the assistant mayor of Novograd Volynsk, was extremely friendly and helpful throughout our stay.

THE JEWISH POPULATION of Novograd Volynsk was mostly old and lived on pensions that didn’t stretch far. The younger people had already immigrated. The American organization, Action for Post-Soviet Jewry, sponsors a number of different programs to help elderly Jews in these circumstances.

Paul Gass and Baruch Korff posing for a photo with some of the members of the Jewish community of Novograd Volynsk

Baruch and I met with the eight leaders of the Jewish community of Novograd Volynsk. The congregation had a Sunday school but was in dire need of books, educational materials, and most important, training. We sensed a willingness to be connected to Judaism but there was a lack of knowledge and expertise. Most people couldn’t read Hebrew and they didn’t know the prayer rituals. We gave them the prayer books, tallit, and other Jewish materials that we had brought from America, and this was met with great excitement.

Paul greeting some of the leaders of the Novograd Volynsk Jewish community

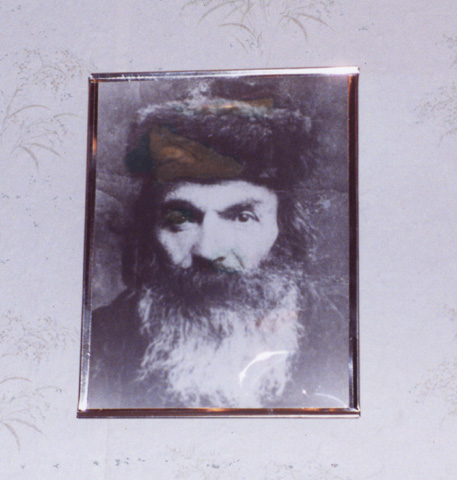

We found the portrait of our relative, Reb Shlomo Goldman, mounted on the wall in the Jewish Community Office

Photo credit: Miriam Weiner of Routes to Roots

We were there on Succoth and had a traditional celebration with the congregation. They had erected a sukka using a green plastic tarp, and we brought an etrog and lulav from home. Baruch recited the Succoth blessings and the congregation provided red wine and cake.

Baruch also held services in the one-room synagogue. Baruch was in his element. He improvised a lot in the way he explained the prayers to the community and clearly touched the people.

The new synagogue was across the street from an old one, which was now used as a shoemaker’s shop. The shoemaker tried to drown out the sound of Jewish prayer by blaring music during our prayers.

Five women with the name of “Goldman” were introduced to Baruch and me. They didn’t know if we were related or not, but on that day, we decided we were all family.

One of the women on the left is Rosa Hardurskya, daughter of Joseph Goldman. (Her mother was Hannah H. Chiem, daughter of Usher). The other woman’s name is not known. Next to Paul Gass on the right are Genya Goldman (who is a Goldman by birth and marriage) and Yesheva Goldman and Ida Goldman who are sisters-in-law. (Ida married Shmuel, and Yesheva married Moishe, both sons of Israel Goldman.) We learned later that Genya was indeed a relative.

Growing up, I had often heard the story of my parents’ honeymoon in Ukraine. They had left Boston with suitcases laden with clothes, including a tuxedo for my father and very expensive evening dresses for my mother to wear on the cruise. When they met the Jews in their ancestral villages, my parents were so moved by the poverty and dire needs that they gave away all their money and clothing, except for the tuxedo and one evening gown, which they wore.

Upon their return, family members had to meet my mother and father at the dock in New York to pay their outstanding bills and give them cash to tip the crew. In 1994, after seeing the desperate condition of the people in Ukraine, I finally understood why my parents had felt so compelled to help.

Chaim Spiegelman and his daughter converse with Baruch.

While I didn’t give away my clothing, I carried extra money, which I gave away during the trip to help alleviate the needs of the people I met.

Most of the people we met in Ukraine, Jew and non-Jew, were extremely friendly and hospitable. When they learned about the great distance we had traveled and the reason for our visit, many invited us into their homes. Their warmth and willingness to share their personal histories and their knowledge of the region’s past was genuine and greatly appreciated.

My grandfather, Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff, had been the chief rabbi of Novograd Volynsk. Since Zvil was the Yiddish name of the town, he was known by the title, “Der Zviller Rebbe.” His job was akin to being the regional governor of the Jewish population in Novograd Volynsk and the surrounding towns. Baruch and I were fortunate enough to meet Jacob Korff’s former assistant, Chaim Spiegelman, who was now 93 years old. Again timing is everything. Chaim was preparing to move the next month from Novograd Volynsk to Israel with his daughter, son-law, and grandson, but he was delighted to meet with us and share his memories.

Mr. Spiegelman showed us the Korff family house at #15 Sobitskaya Street (formerly Utinskaya Street) in Novograd Volynsk. Baruch found the building somewhat familiar but was not sure he recognized it because there had been additions tacked on since Baruch had last seen the house 75 years earlier.

The house where the Korff family lived in Novograd Volynsk

However, two things were exactly as Baruch remembered them: the shed and the outhouse. Baruch recalled that Ukrainian farmers periodically shoveled out the wastes from beneath the outhouse and used it as fertilizer in their fields.

Baruch and I wanted to host a sumptuous dinner for our new friends in Novograd Volynsk. Vitaly arranged to have a kosher meal served at the nicest restaurant in town. After the obligatory toasting the waiters brought out the food: ham and other pork products. They were the best cuts of pork and ham available in the region. Apparently the term “kosher” had been understood as “excellent quality.” I retrieved some cans of tuna from the car for Baruch and me, and we took pleasure in watching our guests enjoy their dinner.

Baruch recognized his family’s outhouse, unchanged after 75 years.

Paul and Leonty Nikolayevich, the assistant mayor of Novograd Volynsk, toasting each other during the banquet

During our visit, Leonty Nikolayevich accompanied us on our tour of the sites of Novograd Volynsk, including the killing fields outside of town where the Nazis executed and buried thousands of Jews in mass graves.

Baruch and I were struck by the revisionist history carved in stone at the memorial sites in Novograd Volynsk and the other sites that we visited in Ukraine and Poland. In the Yiddish inscriptions the Jewish background of the martyrs is described, as is the participation of both the Ukrainians and the Germans in their slaughter. In the Russian, Polish, or Ukrainian inscriptions, Jewish origin is not addressed and only the Germans are blamed for the killings.

Part of the revisionism is understandable in the context of the history of the Soviet Union. The Soviets had abolished religion and officially viewed all ethnic groups as part of the Soviet citizenry. Additionally during World War II, the Germans had murdered 20 to 25 million Soviet citizens; among the dead were an estimated 700,000 to 1.1 million Jews. Soviet officials did not see the statistically small subset of Jewish deaths as being particularly noteworthy. Add to this the fact that antisemitism hadn’t disappeared after the war, further decreasing any incentive to officially acknowledge the unique suffering of the Jewish people during the war, especially the murders in which some Soviet citizens took the role of willing accomplices and executioners.