THE JEWISH CEMETERY IN NOVOGRAD VOLYNSK

Entrance to the old Jewish Cemetery in Novograd Volynsk.

Photo credit: Miriam Weiner of Routes to Roots

BARUCH AND I WENT to the old Jewish cemetery in Novograd Volynsk. The cemetery was overgrown and the Nazis and Ukrainians had removed many tombstones for use in road building. Chickens were permitted roam freely and forage among the graves. It was upsetting to see the graveyard in such deplorable condition.

According to Jewish tradition, the old cemetery was divided into two major parts: one for men, the other for women. Within these sections the people (except for prominent rabbis who got their own gated sections) were buried sequentially by year and date of death.

In the women’s section Baruch and I searched diligently for Gittel’s grave. My mother had paid for a new marker for the site when she visited Novograd Volynsk during her honeymoon, so we figured that it would stand out from the older markers. We came upon gravestones that were placed within a year or two of Gittel’s death, only to discover that the markers for her year had been uprooted and probably used to pave roads. This was quite a disappointment, especially for Baruch.

In the women’s section Baruch and I searched diligently for Gittel’s grave. My mother had paid for a new marker for the site when she visited Novograd Volynsk during her honeymoon, so we figured that it would stand out from the older markers. We came upon gravestones that were placed within a year or two of Gittel’s death, only to discover that the markers for her year had been uprooted and probably used to pave roads. This was quite a disappointment, especially for Baruch.

Baruch’s health was failing and I didn’t realize this at the time. Sometimes he would grab onto me very tightly and on other occasions I actually held him up. Within the year he was diagnosed of pancreatic cancer. But at the time I assumed that he was emotionally overwhelmed.

Paul with Vigory, the head groundskeeper at the Novograd Volynsk cemetery

The poor condition of the cemetery distressed me so much that I asked Vitaly about hiring somebody to clear it. I also wanted the fallen gravestones returned to their upright position so the markers could be read. Vitaly spoke to Vigory, the cemetery caretaker, and they agreed on a price of a few hundred dollars. However, it was soon recognized that this was too big a task for Vigory alone and he asked if he could hire a couple other workers to help him. This sounded reasonable and we upped the price to $500.

I had a good feeling about this friendly man. Vigory wore a yarmulke out of respect and asked permission to burn wood and other debris on the cemetery grounds where there were no grave markers. In the weeks that followed our visit, he and his helpers cleared out and burned much of the overgrowth and fallen trees.

I wondered if $500 was sufficient remuneration but Vitaly assured me that workers in the area normally earned about $30 a month. For the three months or so that it took Vigory and his team to complete the job they would be earning significantly more than usual.

A newer section of the cemetery is in use by the entire population. The more recent graves have images of the deceased etched on the markers. This is common among both the Jewish and Gentile populations.

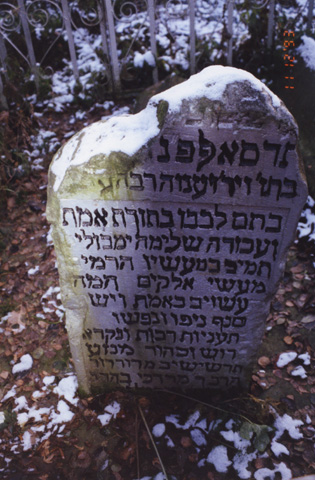

There were tombstones of other Goldmans in the cemetery but the relationship of these Goldmans to Paul Gass’s family is unknown.

VITALY CHUMAK, THE MIRACLE WORKER

Throughout our travels Vitaly smoothed the way at every obstacle and tried to meet the special requests and schedule changes that my uncle and I piled on him—not an easy matter given the dearth of local services. For example, Baruch was quite unhappy about the water pressure problem in our hotel room. So Vitaly arranged for Baruch to have a shower in a private home.

Baruch and I lacked protein in our diets because we eat only kosher meat. In Ukraine the standard fare is greasy pork, and fish products that would be considered fish bait by American standards. Vitaly understood the problem and one day, he rose early and tracked down the owner of the chickens that grazed in the Jewish cemetery. He convinced the owner to sell him the eggs. Vitaly also found freshly made goat cheese and milk. The resulting breakfast was delicious.

In Ukraine, if you have American dollars, you can purchase luxury items such as VCRs, televisions, and cars. If you don’t have money, you have an extremely difficult time just putting food on your plate. Every day is a struggle. Few jobs are available, especially for Jews, and what is available pays poorly. We found that in general, government officials dressed in expensive suits but the typical man or woman on the street was dressed shabbily.

People earn a living in strange ways. For example, in the bigger cities, there are lots of policemen. Each appears to be assigned to certain areas. The policemen are constantly writing tickets and the people are constantly paying them off. Once Vitaly was pulled over in the countryside for speeding. Vitaly got out of the car and as he chatted in a friendly manner, he pulled out his wallet and handed over some cash to the officer. Afterward, Vitaly commented that public officials didn’t get paid enough to support their families so he didn’t mind the payoffs.

KORETS

Baruch and Paul at the Korets’ boundary

BARUCH AND I TRAVELED TO KORETS, a short distance from Novograd Volynsk and met the mayor and the regional director. When I asked to use the bathroom, I was directed to a public outhouse—a six-seater!

I also met the regional director of the hospital in Korets and toured his facility. No government money is available for the upkeep of community services, whether it is roads, schools, government buildings, water mains, etc. The hospital in Korets was a sorry example. This 400-bed facility, a relic from early in the Twentieth Century, lacked not only the basic equipment of modern medicine but it also lacked the fundamentals of plain hygiene. The floor was filthy. No disinfectant was available. Somebody pointed out a blood spill that had been there for a long time. Unbelievably, this primitive facility is the central hospital for the region. Satellite clinics existed in surrounding towns. At the hospital, the regional director treated us to a special meal consisting of vodka, eggs, potatoes, different kinds of salad, and more vodka. He alternately pleaded for help and made toasts.

Paul with the cordial mayor of Korets, Victor Petrovich Kochanovsky

Paul with the Regional Director

Our trip was an emotional tug of war, seeing the poverty that plagued modern-day Ukrainians and dealing with reminders of the horrific fate of the Jews who once lived in the region. During the Holocaust many of the Jews in the area, including some of our relatives, were rounded up and forced to march to killing fields on the outskirts of the towns. There the Nazis forced them to dig their own graves and then slaughtered them, often with the help of willing Ukrainian collaborators. Sometimes our anger at what happened to the Jews in the past prevented us from seeing the better nature of many of the Ukrainians we saw going about their daily lives.

Mayor Victor Petrovich Kochanovsky and the regional director of Korets accompanied us when we went to monuments that commemorated the killing fields in and around Korets.

Baruch and I went to pay our respects at the monuments erected atop the mass graves. Many of the markers had two plaques, one written in Ukrainian and the other in Yiddish. Vitaly translated the Ukrainian inscriptions and Baruch, the Yiddish. The Yiddish markers commemorated the Jews and Ukrainians killed in World War II. The Ukrainian markers paid tribute only to Ukrainians citizens murdered by the Nazis, overlooking the fact that most of these citizens were targeted because they were Jews. The mayor of Korets looked ashamed and embarrassed when he learned this. It was apparently the first time that he saw the memorial from a Jewish perspective.

A farmer plowing his field abutting a killing field memorial. Do his thoughts ever dwell on the massacre that occurred here?

In Korets, we were introduced to Rosa Naumovna Dudoskaya, a teacher of Jewish descent. She knew about the barbaric murder of Baruch’s uncle, Rabbi Yankele Goldman, during the Holocaust. Yankele was Gittel’s brother and the rabbi of Korets. It was to his home that Baruch and his siblings ran after their mother’s murder.

This house may have been the home of Rabbi Yankele Goldman.

According to Rosa, the men responsible for Yankele’s murder were Ukrainians. No German soldiers were present. The baker’s assistant tied a noose around Yankele’s neck and tied the other end of the rope to a horse-drawn wagon. Yankele ran behind the wagon until he tired and stumbled, then he was dragged behind the wagon until he perished. Yankele’s children met the same barbaric death.

Paul and Baruch sitting with Rosa Naumovna Dudoskaya in the mayor’s office in Korets

Rosa had not known the Goldman family before the Holocaust. She came to the area in the middle of the war and along with a few other Jews, she was hidden by a Ukrainian woman. Rosa eventually joined the partisans.

Interestingly, there is a discrepancy in what Rosa told my uncle and me, and what she had told Miriam when she was interviewed by Miriam in November 1993. According to Miriam’s report Rosa remembered the Goldman Family but could not remember occupations or first names. Rosa had been in Siberia during the Holocaust and after she returned to Korets she heard that the Germans had killed the Goldman family. She also showed Miriam a journal published by the Korets Landsmannschaften Society in Tel Aviv, Israel. Perhaps between Miriam’s visit and Paul’s Rosa read the material published by this organization that described Yankele’s death.

Baruch and I went to the ancient Jewish cemetery in Korets. Like the graveyard in Novograd Volynsk, we found it in deplorable condition. High-voltage transmission wires sliced through it and large farm animals were permitted to graze.

Note the transmission lines transecting the old Jewish cemetery in Korets

Antisemitism is still palpable throughout the region. One woman who was casually pushing a baby carriage, approached Baruch and me, smiling, as we stood alongside a monument. When she spotted our yarmulkes, she rushed past us, pushing the carriage as hard as she could.

Most of the expressions of antisemitism that we experienced were more subtle. For example, some Ukrainians told us that all the “good” Jews (i.e. successful ones) had left for America or Israel. The ones who remain are elderly or ill and are on pensions. They are viewed as parasites.

Ukrainians find it acceptable to use Jewish graveyards as pastures for their cattle and sheep.