ZHITOMIR ZAGS ARCHIVES

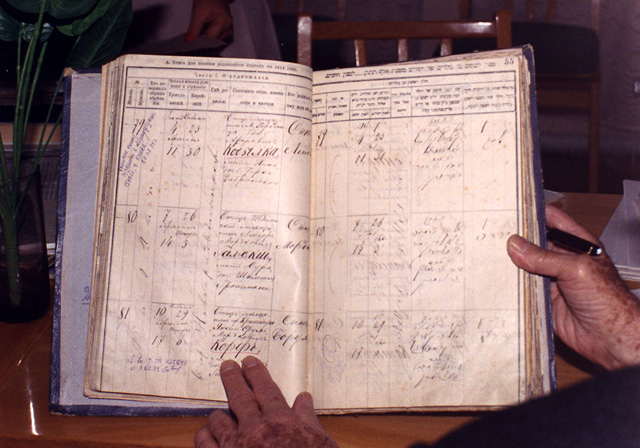

AS THE CHIEF RABBI OF NOVOGRAD VOLYNSK, my grandfather Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff had the responsibility of keeping track of the births, marriages, and deaths of the Jews in the region, and his record keeping was meticulous. He sent his ledgers to the regional capitol, Zhitomir. Vitaly and Miriam had located these ledgers at the Zhitomir ZAGS Archives and so Baruch and I traveled there in the hopes of being able to view them.

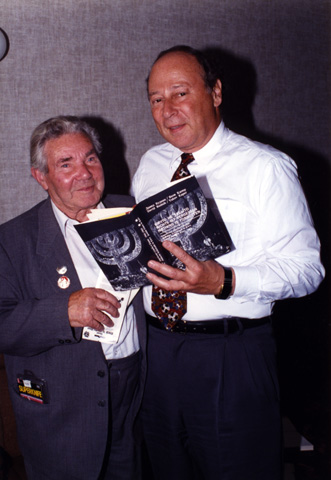

Baruch Korff and Paul Gass at the entrance to the city of Zhitomir

The chief archivist, Natalie Alexeovna Medvedeva, warmed up to Baruch very quickly and he autographed one of his books for her. She brought out some record books containing not only birth, marriages, and deaths of individuals in the Jewish community but also chronicled the brisses and bar mitzvahs. The entries were written in my grandfather’s handwriting.

Baruch autographing a copy of his Nixon book for the director of the Zhitomir ZAGS Archives. He addressed it to “a marvelous and delightful young lady in gratitude.”

We were able to view my grandfather’s record books but weren’t permitted to photograph any of the records within. However, I was allowed to photograph my uncle holding one of the ledgers open.

Baruch Korff at the Zhitomir ZAGS Archives, looking at the vital records for the Jewish inhabitants of Novograd Volynsk

The entries were in the handwriting of Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff. This a close up of a record from 1917 or 1918.

The fatigue and emotional strain on Baruch is clearly captured on this photo as he left the archive

MEDZIBOZH AND BERDICHEV

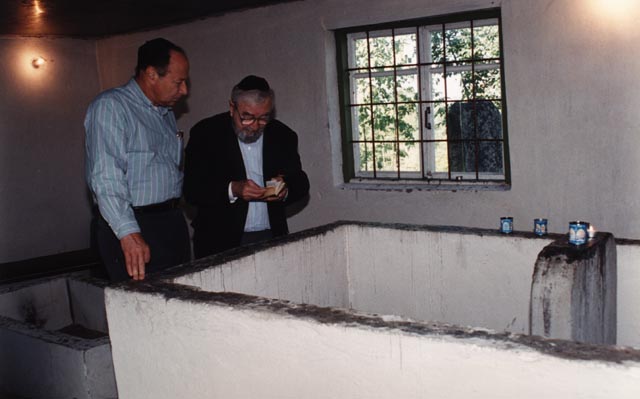

Before heading back to Kiev, we visited the old Jewish cemeteries in the towns of Medzibozh and Berdichev, where the Ba’al Shem Tov and many of his disciples were buried. These graveyards were better maintained than the others, and we noted the existence of recently built ohels. An ohel is a building that covers a below-ground grave. Ohels are not mausoleums. (Mausoleums are elaborate tombs that hold the remains of the deceased in coffins or urns, which are not buried in the ground.)

This ohel is located in the town of Berdichev, and is the burial site of one of Paul’s and Baruch’s ancestors, Rabbi Levi Yitzhak (1740-1809) of Berdichev. He was student of the Maggid (popular preacher) of Mezhirich and son of Rabbi Meir.

Inside a different ohel

With Paul’s help, Baruch could peer into this ohel but there wasn’t enough light for Baruch to read any identifying inscriptions.

KIEV

In Kiev, I met Rabbi Yakov Bleich, the chief rabbi of Kiev and Ukraine. He was a young, Brooklyn-bred Israeli with a strong vibrant personality, who had accomplished a great deal in a short amount of time. Six hundred young people were enrolled in Hebrew schools under his supervision. He also helped Ukrainian Jews immigrate to Israel. He obviously needed money to carry on his money so of course I gave him a donation.

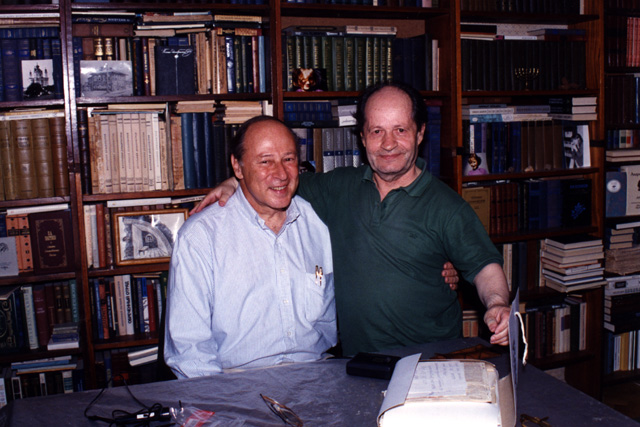

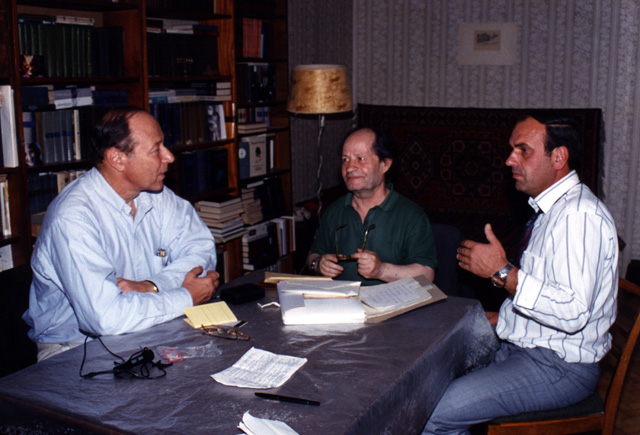

Paul and Ritali Zaslavsky in Ritali’s home; Vitaly’s excellent translation skills permitted Paul and Ritali to have an in-depth conversation.

I met Ritali Zaslavsky, who is a poet and a writer. He wrote “The Holocaust from the Eyes of a Dog.” Ritali gave me a picture from his youth of his friend Naum Moiseevich Mandel. Naum is a famous Russian poet and playwright, who is known professionally under the pen name Naum Kusarvem. Naum adopted a pseudonym because “Mandel” sounded too Jewish and he knew he could never get published in Russia with a Jewish-sounding name. So he chose the surname Kusarvem because it connotes strength and gives the impression that he is from Siberia.

When Naum was young he believed in Communism and wrote idealistic papers about the Communist system. However, he became disillusioned and when he wrote the truth about Communism’s failures, the authorities sent him to a gulag in Siberia. Later he was allowed to return to Moscow.

Read more about PAUL, NAUM, and JEWISH GEOGRAPHY

AT THE REQUEST OF ACTION FOR POST-SOVIET JEWRY, I visited Arkady and Evgenia Rosenberg, an elderly couple who had managed to succeed economically until tragedy struck. Their son Simon had been in an accident and was still hospitalized at the time of the visit. In addition, both Arkady and Evgenia had fallen and broken their hips. Arkady was recovering and walking with walker but it appeared that Evgenia would be permanently disabled. I gave them cash and a tape of Rosalie’s music.

Paul and Vitaly visiting Arkady and Evgenia Rosenberg in their apartment in Kiev

Vitaly had arranged for me to meet David Budnik, the last survivor of the atrocities at Babi Yar. Babi Yar is located in a suburb of Kiev and is the site of the mass murder of 33,751 Jews from Kiev, who were killed over a two-day period. Mr. Budnik had written a book about his experiences.

David Budnik, the last survivor of Babi Yar, presented Paul with a copy of his book describing his experiences.

Read more on Babi Yar.

Reading David Budnik’s book and touring Babi Yar was perhaps the most emotionally draining part of an already emotionally overwhelming trip. In the Passover sedar we are commanded to feel as though we personally were liberated from slavery in Egypt. In Babi Yar, I began to feel as if I had personally witnessed the slaughter. I felt like I was walking on the spirits of the people who were killed there.

Paul walking in the woods near Babi Yar, stepping quite possibly on soil permeated with the ashes of the people murdered there.

To heighten my despair, I saw that the Soviets has placed buildings atop the old Jewish cemetery and the ground where the burnt remains of those murdered in Babi Yar had been scattered. The city planners had shown a complete lack of respect for Jewish sensibilities. Before the war, the cemetery had been in use for hundreds of years, and was quite full. The Soviets built a television station, soccer stadium, and factory atop it.

TV station built on top of the old Jewish cemetery at Babi Yar (above). Part of the cemetery was turned into space for a soccer field and factory (below).

The insensitivity was mind-boggling. A small section of the cemetery still remains but most of the headstones are missing or damaged, and construction of new buildings continues.

The remnants of the old Jewish cemetery

New construction at Babi Yar

The view of the Jewish memorial as Babi Yar is marred by the presence of the TV tower behind it.

Baruch and I figured that the attitude toward war monuments would be the same in Poland as in Ukraine, as the Polish people had also been deemed sub-humans by the Nazis and targeted for extermination. According to information provided by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum web site:

“…millions of Poles—Jews and Catholic alike—were murdered by the SS and police personnel in the field or in killing centers such as Auschwitz-Birkenau and Treblinka. In the ideology of the Nazis, the Poles were considered an inferior ‘race.’ The Germans intended to murder members of the political, cultural and military elite and reduce the remainder of the Polish population to the status of a vast pool of labor for the so-called German master race. It is estimated that between 5 and 5.5 million Polish civilians, including 3 million Polish Jews, died or were killed under Nazi occupation. This figure excludes Polish civilians and military personnel who were killed in military or partisan operations. They number 664,000.”

Nevertheless, the cover up of the unique nature of the Jewish genocide in Poland, as well as in Ukraine, felt like another form of annihilation. Where the Nazis had succeeded in killing millions of Jews during the Holocaust, it seemed like the Ukrainians and Poles were finishing the job by annihilating the memory of Jewish martyrdom and the memory of Jewish existence in these lands for the millennium before the Holocaust.