The Deaths of Lena and Sam

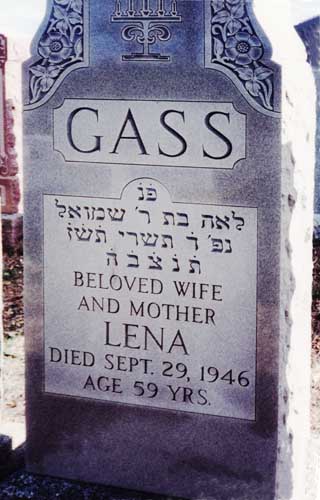

Lena Gass

LENA GASS DID NOT LIVE LONG ENOUGH to see her daughters Anna and Patty marry. She suffered from heart problems, which she tried to hide from her family. Adele Gass was with her when Lena succumbed to her final illness:

“One day she [Lena] was walking on Washington Avenue, and she came up to my house and said, I went shopping, and I got a lot of pain, and the doctor told me it was the heart.

And I said, Ma, I’m going to tell the girls.

She said, If you tell them, I’ll never come up here again.

And right after that she took that fatal heart attack. She didn’t go to the hospital, she was at home and she never came out of it.”

Lena Gass passed away on September 29, 1946. She was 59 years old.

After Lena’s death, and despite his own failing health, Samuel Gass continued to manage real estate and other investments with the help of his son, Max. Harrison Gass remembers visiting his uncle Samuel after he was widowed:

“Shleime was living alone in his big house in Chelsea, the kids had all drifted away. I went to visit one day. I didn’t know him that well, but he was an uncle. I saw this old guy sitting there all alone.

What do you do all day? I asked.

Nothing, he replied.

I know what you need.

What, wise guy, what do I need?

You need a television, I said.

I don’t want it.

It’s crazy not to want it. Television is wonderful. They even have programs in Yiddish and you’ll like it.

I don’t want it, he insisted.

I’m going to buy you one and bring it to you.

I won’t have it. I’ll throw it out.“I didn’t know whether Shleime meant it or not. But a television cost $150 dollars or so, and I was making a lot of money—$35 a week—and I had saved a bit. I thought I’ll do it and that will be my key to G-d, cause Sam was a very religious guy. I don’t say the prayers, not that I don’t believe them. So I said to Shleime,

I’m gonna buy you a television. One day I’ll drive up with the car and I’ll deliver a television.

Don’t bring it in my house, he said.“But I figured he didn’t mean it because obviously a television would be good for him. He never went out, he just sat there on the black sofa with a yarmulke on his head and gloves on his hands, smoking his cigarettes. So I called him a couple weeks later.

I got a surprise for you, I said.

A television? he replied. Don’t bring it. You bring it, I’ll throw you and the set out of the house.“So I didn’t.”

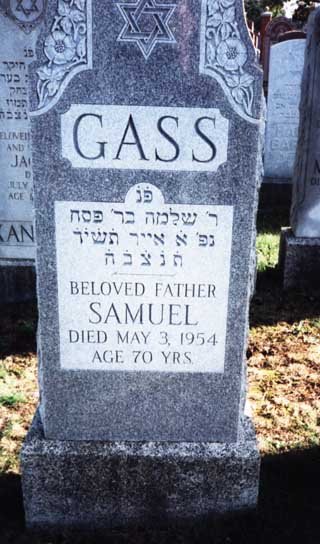

Harrison Gass, was not the only member of the extended Gass family to look in on Samuel Gass in his decline. Lillian Naimark, the wife of Samuel’s nephew, Norman Naimark, remembered that Louis Gass, cared for his cousin Samuel during his last years. Louis would go to 27 County Road and bring food for Samuel and look after him as he struggled with the lung cancer that led to his death on May 3, 1954. Samuel Gass was buried in Chevra Thilim Cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts.

Samuel Gass left no will, so his son, Max, and son-in-law, Joseph Alter, petitioned the court to become the administrators of his estate.[1]

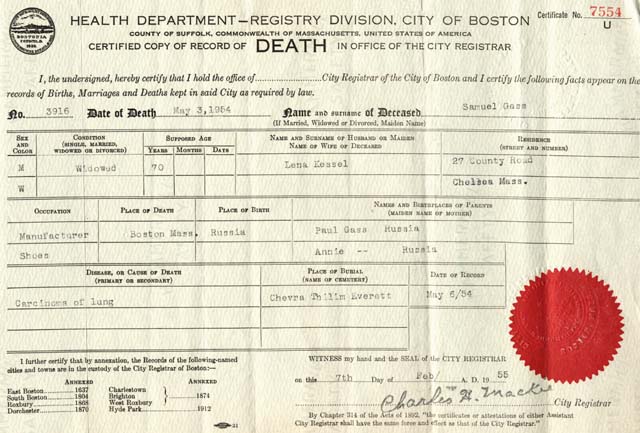

Sam Gass’s death certificate

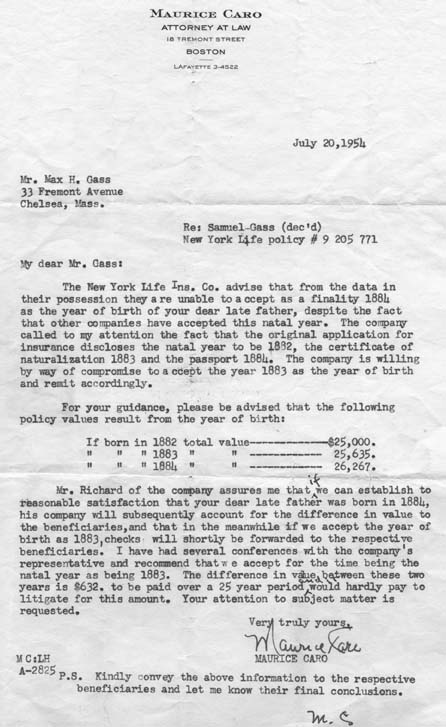

Collecting on a New York Life insurance policy turned out to be difficult too. There was a dispute about Samuel Gass’s true age, and the value of the policy was linked to the year of birth.[2] Apparently, on the original application for insurance, Samuel Gass had put down his birth year as 1882. However, his certificate of naturalization showed his birth year as 1883, and his passport gave it as 1884. The insurance company compromised on the year 1883 and the money was paid out over a 25-year period.[3]

How the insurance company determined Samuel Gass’s age

Paul Gass recounted the complications that revolved around the disposition of the house at 27 County Road:

“After Sam died, the siblings couldn’t agree on what to do about the house at 27 County Road.”

Sam had evidently made it clear to the family that he wished Max and Adele to move into the house when he died, but they did not want the house. Adele, explained why:

“Sam had kept his children financially dependent. He wanted everyone to live at home after they married. Max and I stayed at 27 County Road for only a few months after we returned from our honeymoon. My father-in-law tried to put obstacles in my way about leaving. At that time Max worked for Sam at Lion Shoe but he didn’t collect his salary. Sam took it and gave Max an allowance. But we moved anyway. One day after Max and I had gone, Sam said that if I moved back in he would give me the deed to the house and $30,000. In those days that was a lot of money. And I said to him if he gave me thirty million dollars I wouldn’t move into the house.

“Now when Sam passed away he had no will, because he always had a fear of wills. And when we were at the lawyer’s office, the lawyer said that my father-in- law had wanted me to have the house. And that’s one thing on which all my sisters-in-law agreed, that yes, their father had wanted me to have the house. So I turned around and I said, ‘He couldn’t get me in when he was alive. He’s certainly not going to get me in when he’s dead.’ I didn’t even want to take a spoon. There were a lot of antiques there, too. We sold the place with the furniture, which was all gorgeous inlaid wood, Oriental rugs, beautiful love seats. I wouldn’t take a thing.”

The Lena Gass Trust

SAMUEL GASS HAD INVESTED in real estate on his own and with his brother-in-law, Abraham Gootman. The two men had remained partners in real estate ventures in Belmont and Watertown, Massachusetts, until Gootman’s death, despite their falling out over the purchase of the house at 27 County Road. According to Paul Gass:

“In those days, business was conducted on a handshake and no formal agreement had been drawn between Sam and Abe. I heard from others that after Gootman died, his family’s lawyers came after Sam. Sam didn’t want his name to be thought of in a bad way and he didn’t want to be accused of taking advantage of a widow so he divided the property and gave the choicest real estate to Gootman’s widow. This decision upset Max who thought the properties should have been more evenly divided.”

Some of Samuel’s assets were held in Lena’s name, following common business practice—businessmen often protected themselves by placing their assets in their wives’ names. After Lena Gass passed away in 1946, the assets were transferred to the Lena Gass Family Trust, which was formed on January 31, 1948.

The Lena Gass Trust was an agreement by and between Samuel Gass, all of his children, and the spouses of his married offspring (Joseph Alter, Jonas Ullian, and Adele Gass). One third of the net income of the trust was paid out to Samuel Gass and 2/5 to each of his children. The trust specified that upon the death of Samuel Gass the income was to be evenly divided among his children. If one of the children died that share would pass to the deceased’s offspring. If there were no children, the share would go to the surviving spouse (except if the spouse had lived apart from the deceased prior to the death). Apparently, Samuel Gass prevailed on his children to agree to these terms.

The trust originally held cash and securities as well as the real estate. The investments included stock in Paramount Pictures, Greyhound, Canada Dry, Pennsylvania Power and Light (and several other utilities), City Service Oil company, Sinclair Oil Corporation, United Aircraft Corporation, Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, Rexall Drug Company, RCA, Packard Motor Car Company, and many other stocks. The house at 27 County Road never entered the trust.

The real estate investment consisted of a block of stores on 237-247 Belmont Street in Belmont, Massachusetts. The site was located on the north side of Belmont Street between Worcester and Springfield Streets in the southeastern corner of town. Belmont Street consisted of a mixture of residential and commercial uses, most of the latter were in the form of stores in blocks strips, like the Gass property. They were built in the 1920s and early 1930s. In 1946, the tenants included: Baxter’s Market, Rosetta Dress Shop, Henry Warshauer, Charles Kidder, Pasquale Lacci, Mabel Phelan, Kenneth Hird, Anna M. Ford, and Marie Forsey. The monthly rents ranged from $50 to $65.

Block of stores on 237-247 Belmont Street

As the administrators of Samuel Gass’s estate, Max Gass and Joseph Alter became the trustees for the Lena Gass Family Trust. After Samuel’s death, his five children decided to split the Trust’s assets, so the money and stocks were equally divided. However, they left the real estate in the trust.

To put the value of Samuel Gass’s estate into perspective, Paul Gass described it as follows:

“I think Sam Gass had less than a million dollars when he died. But he still left a lot of money and it was divided five ways. He was not rich rich but comfortable rich. The income from the trust ranged from $600 to $1500 per year per child.”

The Belmont Street property was appraised in March 1960 and valued at $33,000. In January 1977, the family commissioned another appraisal. In the opinion of the appraiser, it was worth $94,000. However, a second appraisal done three months later at the request of State Street Bank and Trust, valued the properties at $65,000. The appraisals included pictures and maps.

In May 1977, the trust was dissolved and a second one, known as Lena Gass Family Trust II, was drawn up by and between Max Gass; his sisters, Minnie Alter and Ida Ullian; and the only child of his deceased sister, Anna. At this time Max’s son, Paul was named trustee along with Max. The trust made no mention of Patty Gass, who by that time had been institutionalized for two decades. It appears that the Gass siblings decided to buy out their sister at this time, although Patty was paid her fair share of disbursements through April 1979, when a mortgage was taken from the Metropolitan Credit Union. The mortgage covered Patty’s fair share.

According to Paul:

“The Lena Gass Family Trust was the one link my father had with the whole family. My father and Joseph Alter were the trustees originally, and then my father became the sole trustee. After he had surgery in 1977, I became a trustee with him.

“After Samuel Gass died, each of the five children of Sam and Lena received a small income from the trust. This ran from $500 to $1500 a year, which was grossly under market. After expenses they were getting $2500 to $7500 as a group, when they should have been getting from $10,000 to $25,000. The rents on the properties were too low. My father had kept the rents depressed, because he believed you only took what you needed. If you didn’t need a lot of money, then you didn’t charge a lot of money. In addition, the tenants took care of everything. They would call him and say, The floor fell in, but don’t worry about it, I fixed it. Max didn’t really have any maintenance worries except for the roof.”

Among the last tenants of the property were Chez Flora (a beauty parlor), Acme Shade, Handy Spa, Holmes Electric, Dale Drug, and Linda’s Donuts. Another long-term tenant was Hutchins Photography Studio. From 1957 to 1962, Hutchins leased 237-239 Belmont Street (store and cellar) for $130 per month. The rent was raised to $150 month for the following five years. Hutchins scaled down his operation between 1968 and 1977, leasing only the store and cellar at 239 Belmont Street. His rent then was $90 a month.

Max Gass, according to Paul, was the epitome of honesty and integrity, especially when it came to managing the Lena Gass Family Trust. He wouldn’t take a penny that belonged to any of them.

“His books were absolutely meticulous, he even split pennies. He had a total system of accounting, not only a cash receipts book and a cash disbursements book, but he had a general ledger. When rents came in you had to record them in three places–in the account for rent ledger, in a general ledger, and then you had to detail it in the checkbook when you made the deposit. It was just unbelievable.

“When my aunt Minnie divorced, the family needed to create some income for her. In addition Patty had been institutionalized and her assets had run down. What we were able to do was take a loan–finance the property–and buy out Patty and Minnie.”

Apparently, Patty was paid in one lump sum. Minnie, however, received monthly checks of $248.35, beginning in June 1978 through May 1985, when she died.

Max sent Minnie the following letter along with her first check:

154 Highland Avenue

Winthrop, Mass. 02152

June 5, 1978Dear Minnie:

I am mailing you the first of eighty-four monthly payments for the purchase of your share of the Lena Gass Family Trust.

It has not been easy to do this and please try to manage the best you can.

Love, Max

Paul Gass remembers this time:

“This was very traumatic for my father. For one thing, the only thing that linked all of the siblings was the Lena Gass Family Trust, so he didn’t want to break it. And there had never been any money owed on the property and he was always scared of debt. My father paid the mortgage off faster than necessary, which means everybody got less income. I think he increased the rents at that time, more to pay off the debt than anything else.

“My father’s greatest fear was that the money given to Minnie would run out. But within two or three months before this would have happened, Minnie passed away. The trust paid for her burial. The money had lasted just long enough. Minnie’s son, Roger Alter, received a check for $1,000 the November after she died.

“The trust was a problem because it was passed down from blood to blood and this created a sore spot with the spouses. When my father passed away I tried to assign all my rights as his beneficiary to my mother but could not do so directly because of the terms of the trust.

“Patty’s money was held by the state, except for money that was set aside for her burial fund.

“I put together a package of increasing rents with the tenants, which gave them the ability to finance a purchase price and a reason to justify buying the property. I had everything fixed up, including putting in a new roof. I then sold the property to the two oldest tenants. One was Handy Spa–my father had known the present owner’s father and grandfather (it had been in the same family for three generations)–and the Donut place, which was run by an immigrant family that my father felt good about.

“I could work with Handy Spa–the owners trusted me because I was Max’s son. They cooperated with me even though I tripled the rent. I used the money to fix up the building in a short period of time–there were a lot of building code violations and part of the roof was falling in. I had the building appraised and I sold it to the tenants for a fair price, $500,000.”

Lena Gass Family Trust, created 31 Jan 1948. Copy in possession of Paul Gass.