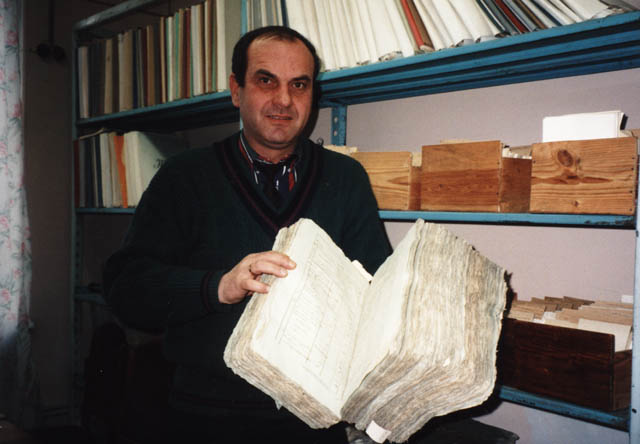

Paul Gass, 1997 |

In 1919, my grandmother Gittel Goldman Korff was killed during a pogrom—an anti-Jewish riot—in the Ukrainian town of Novograd Volynsk. She was only 29 years old and her four young children were by her side. Nearly 80 years later, I felt compelled to walk in the footsteps of my ancestors and I had an encounter with the same mindless prejudice that had led to Gittel’s murder. But I was oblivious to what was happening until after the danger had passed. | |

|

On a trip to explore the Ukrainian shtetls (villages) where my family once lived, I was passing through a town in the vicinity of Novograd Volynsk. My guide, Vitaly, pointed out a dilapidated area, which had once been the Jewish section. |

Gittel Goldman |

|

| I wanted to stop and have my photo taken next to a particularly picturesque ramshackle building. Vitaly argued against stopping, saying we had long distance to drive, but I insisted. | ||

|

|

Vitaly Chumak not only served as my translator and

guide, but he |

I also wanted a photo of residents pumping water from a public well, their only source for household water. As I lingered, a few of the townspeople at the pump people began to talk to Vitaly, and he kept telling me to hurry. I had my back to Vitaly and couldn’t see that the crowd was not particularly friendly, and that even more people were walking quickly to join them. They were yelling at him to get the Jews away from their town, which of course I couldn’t understand because I didn’t speak the language. Vitaly finally got my attention and urged me to hurry into the car. He burnt rubber as we sped away.

When I asked what that was all about, Vitaly downplayed the threat and said something about the people in this town did not encourage visitors. However, my traveling companion, my 80-year-old uncle, Rabbi Baruch Korff, understood the language. He told Vitaly to tell me the complete story.

|

|

| Paul standing in front of the ruins of a

building in a Ukrainian town where a few years prior to his visit a man was killed solely because he was a Jew |

Vitaly then explained that the townspeople here were extremely antisemitic and Jewish visitors were not welcome. In recent years the local citizens had acted on their prejudice and killed a Jew. Although I had been clueless, it was apparent from the tone of Vitaly’s voice and the look on Baruch’s face that we had been in a dangerous situation. This was the first time in my life that I had experienced a physical threat from anti-Semites and I had been too naďve to recognize it.

The menacing nature of the people on the street did not surprise Baruch. At age five, Baruch had witnessed the murder of his mother, Gittel, in Novograd Volynsk. Seven years after his mother’s death, Baruch immigrated to America, and as a young man he trained to be a rabbi. But Baruch was drawn to politics not the pulpit. Over the next 50 years he had an amazing career as a speechwriter for Congressmen, a diplomat, and an advisor to presidents. He never forgot his roots and was always a staunch advocate for the Jewish people. Baruch, however, is best known for his role as President Richard Nixon’s “rabbi” during the Watergate era.

|

|

|

Baruch Korff in the White House with President and Mrs. Nixon |

|

|

|

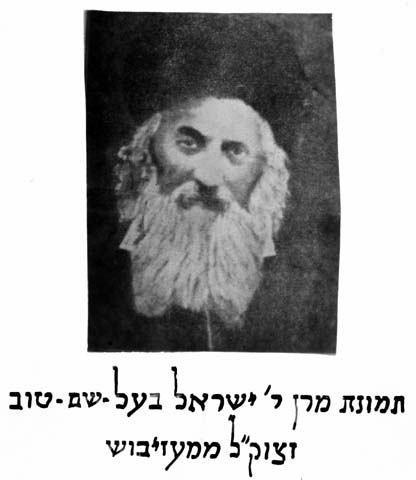

Paul Gass is a descendent of the Ba’al Shem Tov. |

Our trip to Ukraine was sparked by my growing interest in family history. My father’s parents came from the shtetls of Turiysk and Kamen Kashirskiy, and my mother and three of her brothers, including Baruch, were born in Novograd Volynsk (known in Yiddish as Zvil). In addition, on the maternal side, I had the good fortune to be born into a rabbinic family, one that traces its roots directly back to the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidic Judaism. The Ba'al Shem Tov's given name was Yisroel ben Eliezer (Israel, son of Eliezer). He was called the Ba'al Shem Tov--Master of the Good Name--because he emphasized the common good and the need for a positive attitude. Much of the history of the Ba'al Shem Tov and the Hasidim unfolded in my ancestral towns.