NOVOGRAD VOLYNSK (continued)

|

NOVOGRAD VOLYNSK (continued) |

|

The Jewish population of Novograd Volynsk was mostly old and lived on pensions that didn’t stretch far. The younger people had already immigrated. The American organization, Action for Post-Soviet Jewry, sponsors a number of different programs to help elderly Jews in these circumstances.

|

|

Paul Gass and Baruch Korff posing for a photo with some of the members of the Jewish community of Novograd Volynsk |

Baruch and I met with the eight leaders of the Jewish community of Novograd Volynsk. The congregation had a Sunday school but was in dire need of books, educational materials, and most important, training. We sensed a willingness to be connected to Judaism but there was a lack of knowledge and expertise. Most people couldn’t read Hebrew and they didn’t know the prayer rituals. We gave them the prayer books, tallit, and other Jewish materials that we had brought from America, and this was met with great excitement.

|

|

|

Paul greeting some of the leaders of the Novograd Volynsk Jewish community |

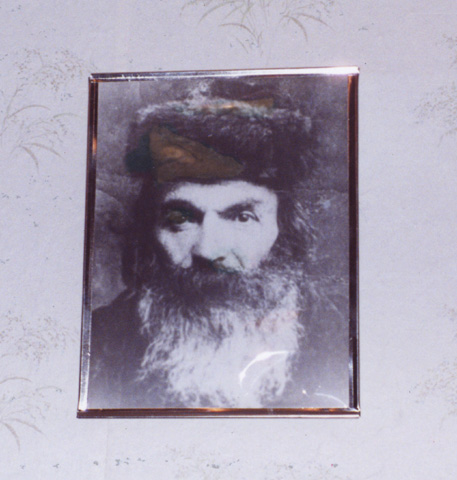

We found the portrait of our relative, Reb Shlomo

Goldman, mounted on the wall in the Jewish Community Office |

We were there on Succoth and had a traditional celebration with

the congregation. They had erected a sukka using a green plastic tarp, and we

brought an etrog and lulav from home. Baruch recited the Succoth blessings and

the congregation provided red wine and cake.

Baruch also held services in the one-room synagogue. Baruch was in his element.

He improvised a lot in the way he explained the prayers to the community and

clearly touched the people.

The new synagogue was across the street from an old one, which was now used as a shoemaker’s shop. The shoemaker tried to drown out the sound of Jewish prayer by blaring music during our prayers.

Five women with the name of “Goldman” were introduced to Baruch and me. They didn’t know if we were related or not, but on that day, we decided we were all family.

|

|

One of the women on the left is Rosa Hardurskya, daughter of Joseph Goldman. (Her mother was Hannah H. Chiem, daughter of Usher). The other woman’s name is not known. Next to Paul Gass on the right are Genya Goldman (who is a Goldman by birth and marriage) and Yesheva Goldman and Ida Goldman who are sisters-in-law. (Ida married Shmuel, and Yesheva married Moishe, both sons of Israel Goldman.) We learned later that Genya was indeed a relative. |

Growing up, I had often heard the story of my parents’ honeymoon in Ukraine. They had left Boston with suitcases laden with clothes, including a tuxedo for my father and very expensive evening dresses for my mother to wear on the cruise. When they met the Jews in their ancestral villages, my parents were so moved by the poverty and dire needs that they gave away all their money and clothing, except for the tuxedo and one evening gown, which they wore.

|

|

Chaim Spiegelman and his daughter converse with Baruch. |

Upon their return, family members had to meet my mother and

father at the dock in New York to pay their outstanding bills and give them cash

to tip the crew. In 1994, after seeing the desperate condition of the people in

Ukraine, I finally understood why my parents had felt so compelled to help.

While I didn’t give away my clothing, I carried extra money, which I gave away

during the trip to help alleviate the needs of the people I met.

Most of the people we met in Ukraine, Jew and non-Jew, were extremely friendly

and hospitable. When they learned about the great distance we had traveled and

the reason for our visit, many invited us into their homes. Their warmth and

willingness to share their personal histories and their knowledge of the

region’s past was genuine and greatly appreciated.

My grandfather, Grand Rabbi Jacob Korff, had been the chief rabbi of Novograd

Volynsk. Since Zvil was the Yiddish name of the town, he was known by the title,

"Der Zviller Rebbe." His job was akin to being the regional governor of the

Jewish population in Novograd Volynsk and the surrounding towns. Baruch and I

were fortunate enough to meet Jacob Korff’s former assistant, Chaim Spiegelman,

who was now 93 years old. Again timing is everything. Chaim was preparing to

move the next month from Novograd Volynsk to Israel with his daughter, son-law,

and grandson, but he was delighted to meet with us and share his memories.

Mr. Spiegelman showed us the Korff family house at #15 Sobitskaya Street (formerly Utinskaya Street) in Novograd Volynsk. Baruch found the building somewhat familiar but was not sure he recognized it because there had been additions tacked on since Baruch had last seen the house 75 years earlier.

|

|

|

The house where the Korff family lived in Novograd Volynsk |

|

|

|

Baruch recognized his family’s outhouse, unchanged after 75 years |

However, two things were exactly as Baruch remembered them: the shed and the outhouse. Baruch recalled that Ukrainian farmers periodically shoveled out the wastes from beneath the outhouse and used it as fertilizer in their fields.

Baruch and I wanted to host a sumptuous dinner for our new friends in Novograd Volynsk. Vitaly arranged to have a kosher meal served at the nicest restaurant in town. After the obligatory toasting the waiters brought out the food: ham and other pork products. They were the best cuts of pork and ham available in the region. Apparently the term “kosher” had been understood as “excellent quality.” I retrieved some cans of tuna from the car for Baruch and me, and we took pleasure in watching our guests enjoy their dinner.

|

|

Paul and Leonty Nikolayevich, the assistant mayor of Novograd Volynsk, toasting each other during the banquet |

During our visit, Leonty Nikolayevich accompanied us on our tour

of the sites of Novograd Volynsk, including the killing fields outside of town

where the Nazis executed and buried thousands of Jews in mass graves.

Baruch and I were struck by the revisionist history carved in stone at the

memorial sites in Novograd Volynsk and the other sites that we visited in

Ukraine and Poland. In the Yiddish inscriptions the Jewish background of the

martyrs is described, as is the participation of both the Ukrainians and the

Germans in their slaughter. In the Russian, Polish, or Ukrainian inscriptions,

Jewish origin is not addressed and only the Germans are blamed for the killings.

Part of the revisionism is understandable in the context of the history of the

Soviet Union. The Soviets had abolished religion and officially viewed all

ethnic groups as part of the Soviet citizenry. Additionally during World War II,

the Germans had murdered 20 to 25 million Soviet citizens; among the dead were

an estimated 700,000 to 1.1 million Jews. Soviet officials did not see the

statistically small subset of Jewish deaths as being particularly noteworthy.

Add to this the fact that antisemitism hadn’t disappeared after the war, further

decreasing any incentive to officially acknowledge the unique suffering of the

Jewish people during the war, especially the murders in which some Soviet

citizens took the role of willing accomplices and executioners.