WARSAW, POLAND

|

WARSAW, POLAND |

|

We took a flight from Kiev to Warsaw, where my mother, Baruch, and their siblings had lived between 1924 and 1927 or so.

|

|

Warsaw synagogue |

Baruch and I visited the site of the Warsaw Ghetto, the largest of the ghettos established by the Germans. It is also where the most successful attempt by Jews to resist the Nazi killing machine occurred. The main monument commemorating the uprising in the ghetto did not mention the Jewish ethnicity of the martyrs who died there.

|

|

|

The monument commemorating the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Close-up below |

|

Click here for more information on the Warsaw Ghetto.

|

|

|

The site of the Warsaw Ghetto today looks like a typical neighborhood in Warsaw. |

|

The headquarters of Mordecai Anielewicz, the leader of the Jewish resistance,

had been housed at Miła 18. On May 8, 1943 about 100 brave fighters died there

when the Germans threw canisters of poison gas into the building. Some of the

fighters committed suicide rather than dying at the hands of the Germans. A few

escaped and the Germans killed the rest.

Nothing remains of the original house but a stone engraved in Hebrew, Yiddish,

and Polish marks this historic spot. A short distance from Miła 18 was the home

where Baruch and his siblings had once lived, Miła 27. The original building was

also destroyed during the uprising.

|

|

|

Miła 27 |

|

Pawiak Prison Museum and other Warsaw sites

|

|

|

Pawiak Prison Museum |

Pawiak was a prison built in the 1830s and

appropriated by the Germans in 1939. Located inside the Warsaw Ghetto, it was

used to detain political prisoners, mainly Catholics, but some Jews, too.

Approximately 100,000 people were imprisoned here and tortured. About 37,000 of

them were executed inside the prison; and 60,000 were deported to concentration

camps. After the ghetto was destroyed during the Warsaw Uprising, the Germans

used the ruins surrounding the prison as an execution area. In August 1944, the

Germans dynamited the prison to destroy the evidence of their crimes.

After the war, the prison became a symbol of Polish resistance and martyrdom,

and a museum was built in what was left of the basement. Part of the exhibition

pays tribute to the Polish people for their willingness to fight for freedom.

The other part houses reconstructions of prison cells.

|

|

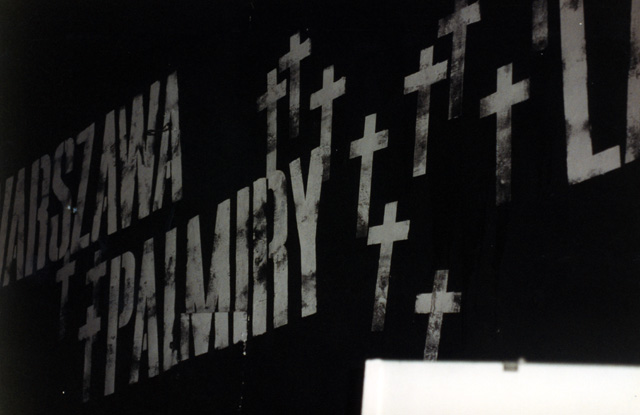

Crosses on the ceiling of the Pawiak Prison Museum pay tribute to Catholic martyrs who were imprisoned there. |

|

Nailed to this tree outside Pawiak Prison Museum are memorials to some of the prison’s victims. None of the prisoners designated have Jewish-sounding names. |

|

Baruch thought that many of the artifacts in the museum were distinctly Jewish, not Catholic. So he asked one of the curators why there was no acknowledgment of the Jewish martyrs who were detained in the prison. The response was there were “some” Jewish artifacts, but the curator gave the distinct impression that the number was quite small, and by implication, that the number of Jews who passed through the prison was too insignificant to be bothered with.

|

|

|

We took time off from our sightseeing to pay a visit to the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw. Baruch and I were received by the assistant ambassador. |

Baruch and I visited a monument at the Umschlagplatz, the collection point where Jews and Polish Catholics were sent before boarding cattle cars and being shipped to Treblinka or Auschwitz.

|

|

|

My chauffer for the trip to Majdanek |

Interestingly, at the memorials we went to in Ukraine and Poland, the term “Nazis” was never used to describe the German perpetrators. They were simply referred to as “Germans” or “fascists,” the latter being an indictment of the German economic and political system.

We also visited the Jewish Cultural House in Warsaw

is the home of the E.R. Kamińska State Jewish Theater. It is heir to the works

of Shalom Aleichem and other outstanding Jewish playwrights. Most of the actors

are not Jewish but it is the last theater in the world devoted wholly to Yiddish

works, including contemporary plays with Jewish themes. The plays are performed

in Yiddish and translated into Polish through headphones. The people involved

with the theater wanted to establish a Jewish museum in Warsaw that acknowledged

the immense contribution that Jews had made to Polish life,

The Jewish Cultural House also contains the Słowo Żydowskie, Poland’s only

Jewish newspaper (published in both Polish and Yiddish), and the Cultural

Society of Jews. One of the goals of the society is to establish a museum that

commemorates the immense Jewish contributions to Polish life.

Baruch arranged to have a driver take me to Concentration Camp Majdanek in

Lublin because he wasn’t feeling up to going. The driver and I had diametrically

opposed versions of history. The movie “Schindler’s List” was playing in Warsaw

at that time and I asked the driver what he thought of it. He said it was just a

movie production. I explained that it was based on a true story but he insisted

it was fiction. I told him that I knew one of the survivor’s of the real

Schindler’s List (a woman who lived in Framingham, Massachusetts) and that the

film was based on fact. But the driver was completely unconvinced. “That’s your

opinion,” he said.

Click here for more information on Majdanek Concentration Camp.

|

|

|

In Kazimierz Dolny, Poland, I came to a memorial

wall made of the fragments of Jewish gravestones from the remains of the large

Jewish cemetery. I stopped and said Kaddish. I was heartened that the citizens

of the community had turned the cemetery into a memorial and had not used the

land for other purposes. Nevertheless, I left eastern Europe with the feeling

that Jews were being written out of history. The issue boils down to this: if

the Europeans didn’t care about the Jews while they were living amongst them,

why should they now care enough to preserve the Jewish legacy?